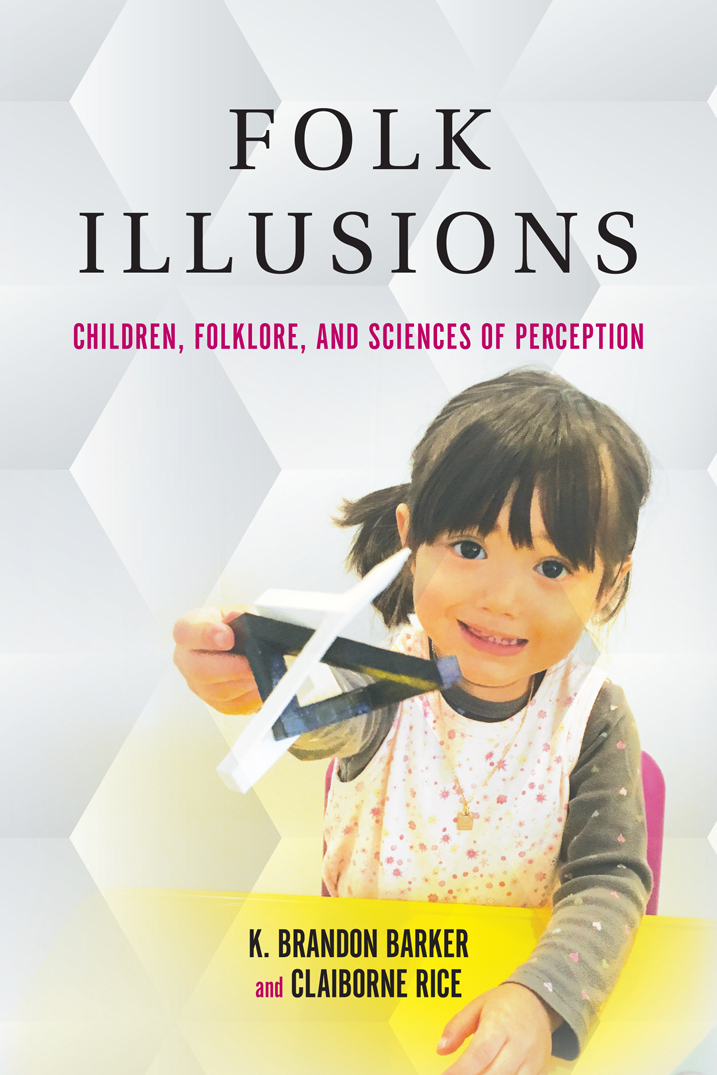

FOLK ILLUSIONS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2019 by Brandon Barker and Clai Rice

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-04108-1 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-253-04109-8 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-04110-4 (ebook)

1 2 3 4 5 24 23 22 21 20 19

To our families

CONTENTS

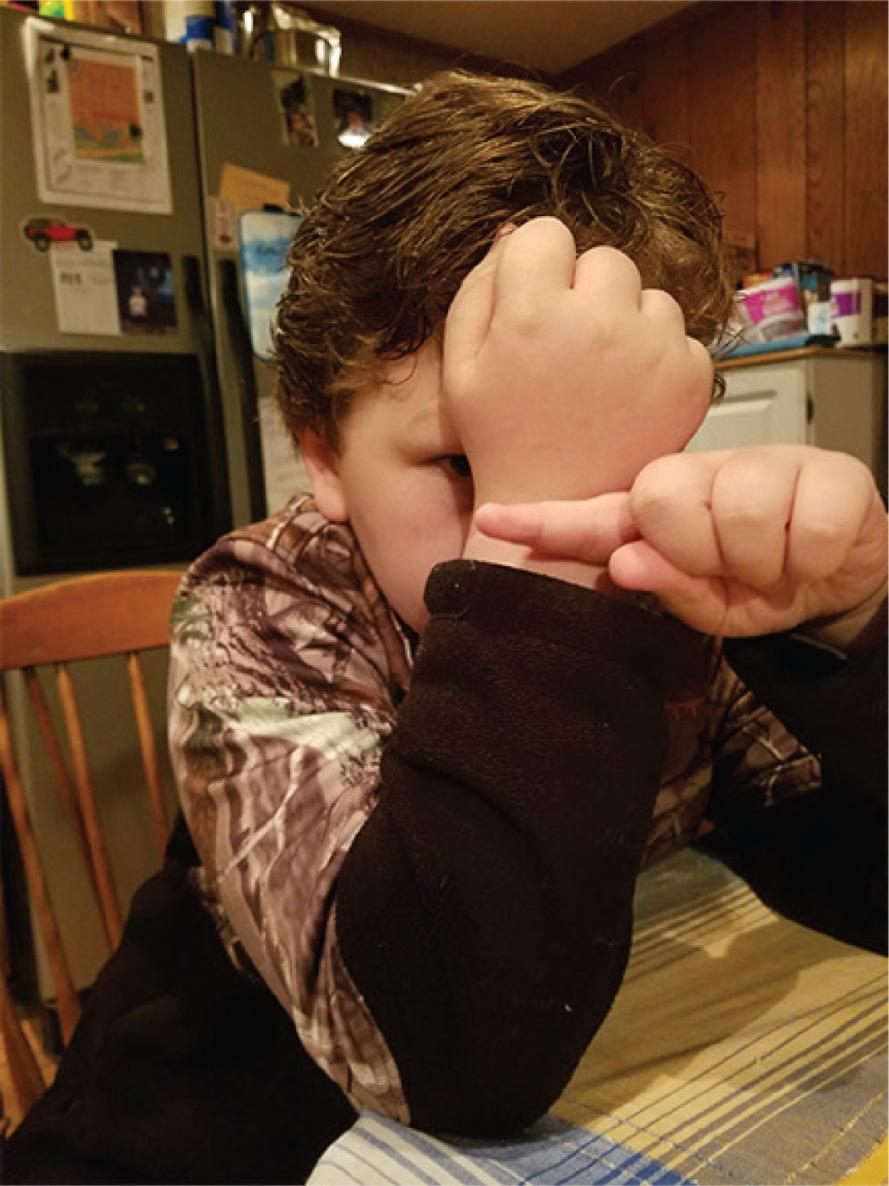

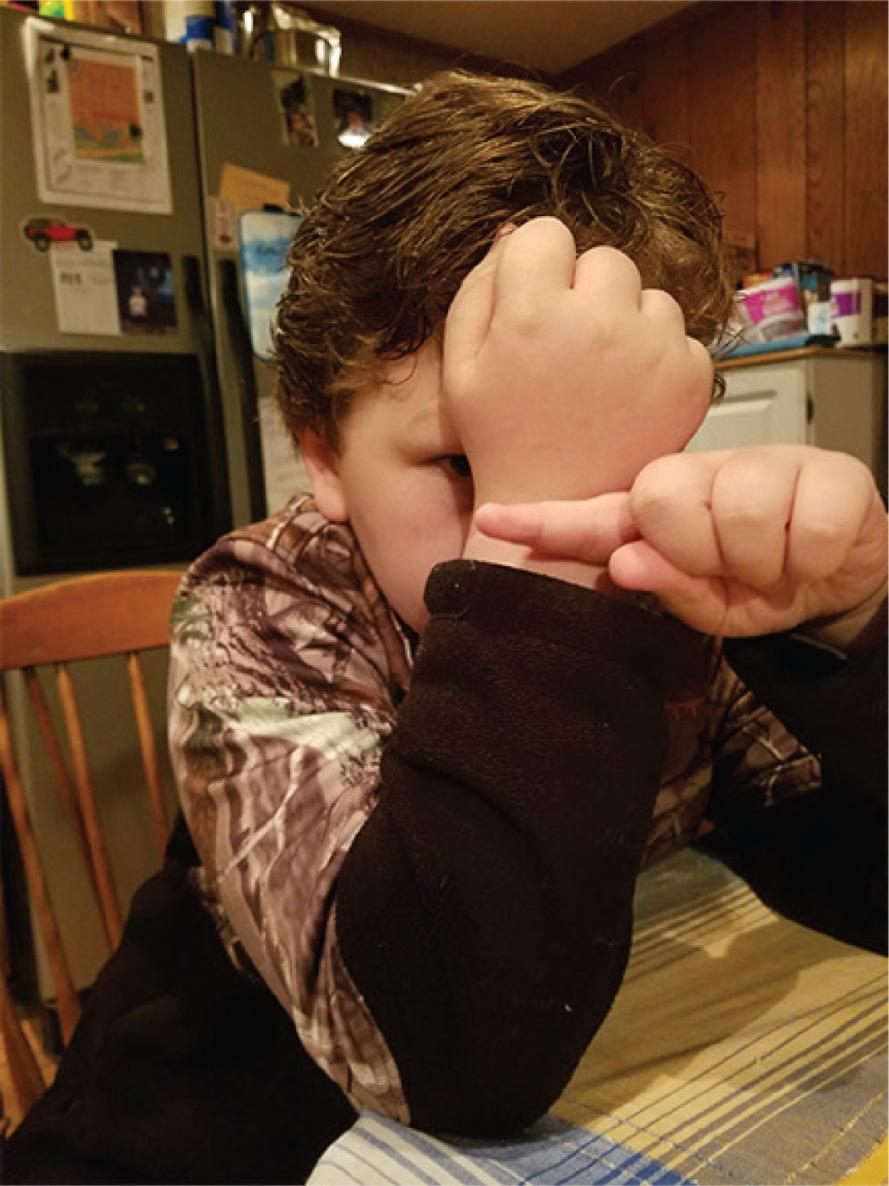

G O LIKE THIS .

Hold your right hand out in front of you so that your arm extends perpendicularly from the center of your chest. Your right palm should be facing up so that you can see the underside of your right forearm. Now, make a fist with your right hand. The next step is simple. Pull your arm up in front of your face so that the distal portion of your forearm touches your nose and the knuckles of your fist point toward the sky. From this position (you can do this while you read), point the index finger on your left hand in the standard pointing position. Now, hold that pointed finger so that it is parallel to the ground and pointing to your right. Here comes the fun part. While staring straight ahead, slowly pass your pointed finger in front of your right forearm that is in front of your face.

Zanes mother, Rose, first relayed Zanes narrative description of the tricks origins in the spring of 2017. That semester, Rose was enrolled in Brandon Barkers Childrens Folklore course at Indiana University. She developed a habit of showing Zane, her nine-year-old son, some of the games, rhymes, and other activities that she learned about in class. Then one evening over dinner, Zane showed his mother the shrinking/disappearing-finger illusion we described above. What an excellent trick! Correctly, Rose recognized that we would be interested to learn about the trick, so she asked Zane where he had learned it. His story, Rose told us, went something like this: Zanewhile sitting in school one daywas bored and discouraged. Being strapped to a school desk can be torturous for children who value playful, fully embodied experience over pencils and paper. In this state of mind, Zane sort of found himself in the position that facilitates Zanes illusion as he, in frustration, rested his forehead in his palm. From there, Zane told his mother, he simply fiddled with his fingers until he discovered the visual illusion.

It is an appealing taleboth a testament to a bored nine-year-olds ingenuity and a reminder that children do not need extravagant toys or electronic charms in order to entertain themselves. But as we said, the story is more complicated than just this. In a fortuitous schedule overlap, Zane had a free day to visit our Childrens Folklore course the following Monday because his school was closed for the observance of Presidents Day. On that Monday, we were discussing Yo-Mama joke cycles and toast-like battling traditions among children and teens. Much of youthful folklore, and thus much of a course on childrens folklore, pushes the boundaries of acceptability. Children possess a keen knack for walking all over taboos. As a true consultant, Zane was prompted to share with us a Yo-Mama joke. After a sly, careful glance at his mother, he delighted the room: Yo mama is so ugly, she tried to enter an Ugly Contest, and the judges said, Sorryno professionals! Roses fellow students burst into cacophonous laughter. We had all just broken the rules by allowing her nine-year-old to perform for us what a child is supposed to perform only for his peers. It was a great pleasure and, clearly, Zane was a star.

Fig. 0.1. Zane performs Zanes illusion at his kitchen table.

Feeding off of this success, Brandon explained to Zane that the class was also very happy to have learned about Zanes illusion and that they had all been impressed with the trick. Sensing the moment was right, Rose then asked Zane to re-create his tale of discovering Zanes illusion:

Mom, I dont know what youre talking about. Zane blinked up at his mother.

Remember, at the dinner table, you told me about how you were frustrated at school, and how... Tilting her head, Rose tried to jog Zanes memory.

Blink... Blink... I never said that, Mom. I dont know what youre talking about.

Rose, surprised and a little embarrassed, laughed at Zanes apparent amnesia. As the conversation moved on, the rest of us chalked Zanes memory lapse up to the precarious mind of children. Brandon consoled her: Theyll do that to you.

It turns out, Zanes illusion is only one of the many forms of childrens play that distort the boundaries between illusion and reality. In the pages and chapters that follow, we will outline our understanding of these kinds of play by examining many such forms, and we will argue that these forms make up a discrete genre of folklore. In problematizes the boundaries of our genre in the context of a well-known form of childrens supernatural folklore: mirror summonings. Our concluding chapter outlines our notion of body acquisition, after which we provide an appendix of all the illusions that children, youths, and young adults have taught us. (Zanes illusion is B14.)

The appendixthough it is situated at the end of the bookis a good place to start. More than once, we will recommend taking a look at it before completing the chapters that precede it. And we do so now if for no other reason than to remind you that you too once performed Zanes illusionlike activities. If you are thinking that maybe you have never performed a trick like Zanes illusion, let us start by cautioning you: What is true of perception is true for memory. Assumptions carry great risks.

W E ARE INDEBTED TO MANY PEOPLE FOR VARIOUS kinds of contributions to this book. First and foremost, we are thankful to the children and youths who have taught us how to play with illusions. We thank the teachers and administrators at St. Cecilia Middle School in Broussard, Louisiana, and at Parents Day Out Preschool in Bloomington, Indiana, for allowing us to break up the routines of their days. Similarly, we thank the Evangeline Area Council, Boy Scouts of America, for their willingness to speak about the illusions their young Scouts perform. We thank Cheryl Hesse for hosting our very first opportunity to observe kids performing folk illusions at her beautiful and hospitable home in Lafayette, Louisiana. We are grateful to several youthful star performers: Aoife, Lucas, Monica, Sofia, Jacob, Calvin, Finley, Zane, Addy, and Lilly. And to the students at Indiana University and the University of Louisiana who have helped us fill out our catalog, we say thank you.

We have benefited from the rich intellectual support of the Department of English at the University of Louisiana and the Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology at Indiana University. In Louisiana, we thank, especially, our friends and colleagues John Laudun, Barry Ancelet, Marcia Gaudet, Shelly Ingram, Skip Fox, Jonathan Goodwin, Mark Honegger, Wilbur Bennett, Yung-Hsing Wu, Jerry McGuire, Marthe Reed, Elizabeth Bobo, Carmen Comeaux, Keith Dorwick, and many others whose feedback and reinforcement have been invaluable. In Indiana, we developed enriching relationships with Diane Goldstein, Pravina Shukla, Gregory Schrempp, John McDowell, Jason Jackson, Ray Cashman, David McDonald, Tim Lloyd, Sue Thuoy, Fernando Orejuela, Daniel Reed, Alan Burdette, Ruth Stone, Rebecca Dirksen, and Alisha Jones. Talking for hours and hours with our friend Daniel Povinelli has sharpened both our thinking and our work with folk illusions. The same is true for our friend Henry Glassie, who, over many cups of coffee, has guided and encouraged this project, and we thank him for reading an early draft.