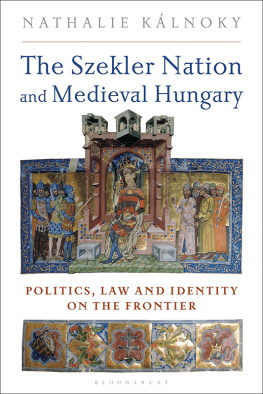

If a Szekler hangs the Szekler flag on a public building, I will string him up alongside.Mihai Tudose, Romanian Prime Minister,Bucharest, 1 November 2018.

After 1,000 years in Transylvania and 100 in Romania, the Szeklers have defiantly preserved their sense of identity, which, in everyday life, is manifested by their flag and their perseverance in the use of the Hungarian language. The language, a Uralic island in an Indo-European sea, has a rich but hermetic vocabulary, in which nouns have thirty cases only seventeen in daily use. It is a barrier difficult for outsiders to breach. In their new environment in Romania, it is the Szeklers who surmounted the obstacle, adding the Romanians language to their own, but their equally rich cultural and institutional heritage, represented by their flag, lives on and seems to irritate. It is seen to embody the Szeklers individuality within their broader Hungarian heritage in Romania.

The kingdom of Hungary was founded about the year 1000 around two seminal principles. One, the pagan Grand Prince Gza (AD 940997) had embraced the Latin rite of Christianity, while the Greek rite, centred on Constantinople, was still present in Transylvania. Two, in his admonition to his son and successor Emeric, Hungary first crowned King, Stephen, affirmed: nam unius lingue uniusque moris regnum imbecile et fragile est (for a Kingdom with [only] one language and one custom is weak and fragile).

The first of these principles allowed Hungary to affirm its place in Europes occidental Christianity and avoid sharing the short-lived fate of earlier arrivals like the Huns and Avars. The kingdom soon flourished at the eastern frontier of Latin Christianity.

In line with the second, King Stephens precept, it played host to a number of populations, Pechenegs, Cumans, Iasians and Szeklers. Order was consolidated in the kingdom by firmly assigning the newcomers places to settle and functions to fulfil. The Pechenegs, erstwhile eastern enemies, were installed to the west, the Cumans and Iasians in the centre around the king and the Szeklers as border guards along the frontiers, essentially in the southeastern corner of the kingdom, in Transylvania.

The nascent kingdom felt strengthened by this diversity in its ranks and granted the different communities collective privileges for their service. The existence of a special juridical status for different, not necessarily ethnic groupings in the Hungarian kingdom ensured their loyalty and standing. With their integration, the maturing kingdom came to resemble its western neighbours and the privileged communities faded, merged and eventually let their identity wane.

All but one. Assigned by the king to guard the Eastern frontier of the kingdom, the Szeklers adapted their structures and customs from their time in the Steppes to their new environment in a Western European kingdom. In so doing, they achieved institutional autonomy within a modern state and cemented their sense of historical individuality. They, in turn, applied King Stephens admonition of gaining strength through the assimilation of ethnic diversity within their ranks, as is shown by the toponymic curiosities in the Szeklerland. These sometimes called into question the Szeklers ethnic authenticity. Slavic place names jostle with Armenian, Cuman, Pecheneg, Iasian and Vlach villages on a map of the Szeklerland. And, while their neighbours are tempted to pride themselves on ethnic purity, the Szeklers pride is in their system of laws and self-governance. The acceptance by ethnic communities of the Szeklers obligations and rights constituted their integration.

In todays post-Marxian idiom, the Szeklers privilege reeks of undeserved advantages enjoyed by a socially superior class over the common man. In France, the Bretons privilege, accorded and confirmed by the French kings related not to creature comfort but to their right to determine their own destiny with a parliament and judiciary rules of their own. It was summarily abolished by the French revolution, with the death knell of Libert, galit. (Fraternit was yet to be invented and never codified.) The Bretons identity survives, however. Their black-and-white flag is ever present on French bumper stickers; their folklore joins that of their Celtic cousins in popular festivals with Irish, Scottish, Galician and Asturian participants. But then, Breton identity does not test that of France.

In medieval Szekler society, libert meant to have no subservience to any lord between them and the king and to move about freely; galit was the right of all to vote at assemblies and to elect officials and judges. Fraternit was a day-to-day practice, though occasionally giving way to vociferous altercations which ended up before their elected judges and gave rich subject matter for this study to deal with.

To quote the Szekler author ron Tamsi: The world was created for everyone to have someplace to call his home. Wistful sentiment for a lifelong migrant to proclaim. Born in Hungarian Transylvania, in the Szeklerland, he emigrated to the United States in 1923 when Transylvania became part of Romania, returned to Transylvania three years later and moved to Hungary in 1944, where he died. His writings breathe the folklore of his origins. His perception is evident for Szeklers, for whom home refers to their land in Transylvania but equally to their identity: the framework of tradition, laws and customs carried over from their place in the Steppes. Its presence is a spice that helped define bearing, attitude in all manner of situations wherever Szeklers found themselves. An American source refers to it as their extreme superiority complexes (cf. Lszl Krti, The Remote Borderland).

True, they are still conscious of their status as original nobles, Uradel in German, nobles already on arrival in the Pannonian basin, as cavalrymen. This was seamlessly confirmed by the kings assignment as guards of the Eastern border.

Anachronism aside, it is tempting to liken the preamble we the inhabitants of in statutes voted by Szekler communities to the all-important we the people in more recent charters. They voted of a common accord the sets of laws under which they agreed to live. A formal variant to the more casual accumulation of customary or common laws observed elsewhere. Hence the original, French edition of this work, titled Les Constitutions et Privilges de la Noble Nation Sicule put the first word in the plural. It was a PhD thesis where this contextual accuracy was natural in the academic world. Nevertheless, lay readers of the first drafts of the English translation invariably suggested the term be put in the singular, no doubt with the constitution of the United States of America in mind. Still, the we the people of the preambles, with the voting of constitutions by the entire population is a measure of the precocity of the Szekler system of laws and institutions, in the very first years of the sixteenth century.

But is this democracy?

The American Constitution dates from 1787; the French was adopted in 1791, by constituent assemblies in the name of the people. England perseveres without a written constitution, the rule of law based essentially on judicial precedent, supplemented by legislation. They are readily recognized as archetypes of modern, representative democracy.

![Nathalie Nahai [Nathalie Nahai] - Webs of Influence: The Psychology of Online Persuasion, 2nd Edition](/uploads/posts/book/124053/thumbs/nathalie-nahai-nathalie-nahai-webs-of.jpg)