Alisha Rankin is assistant professor of history at Tufts University. She is the coeditor of Secrets and Knowledge in Medicine and Science, 15001800.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2013 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2013.

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-92538-7 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-92539-4 (e-book)

ISBN-10: 0-226-92538-2 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-92539-0 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rankin, Alisha Michelle, author.

Panaceias daughters : noblewomen as healers in early modern Germany / Alisha Rankin.

pages cm. (Synthesis : a series in the history of chemistry, broadly construed)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-226-92538-7 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 0-226-92538-2 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-226-92539-4 (e-book) ISBN 0-226-92539-0 (e-book)

1. Women healersGermanyHistory16th century. 2. PharmacyGermanyHistory16th century. I. Title. II. Series: Synthesis (University of Chicago Press)

R146.R36 2013

610dc23

2012021911

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Panaceias Daughters

Noblewomen as Healers in Early Modern Germany

ALISHA RANKIN

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

A series in the history of chemistry, broadly construed, edited by Angela N. H. Creager, Ann Johnson, John E. Lesch, Lawrence M. Principe, Alan Rocke, E. C. Spary, and Audra J. Wolfe, in partnership with the Chemical Heritage Foundation

Recent books in the series

The Secrets of Alchemy

Lawrence M. Principe

Inventing Chemistry: Herman Boerhaave and the Reform of the Chemical Arts

John C. Powers

Genentech: The Beginnings of Biotech

Sally Smith Hughes

Image and Reality: Kekul, Kopp, and the Scientific Imagination

Alan J. Rocke

For John

Contents

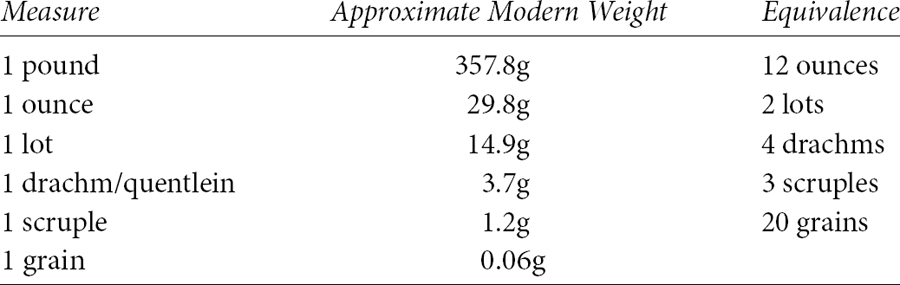

Early Modern Pharmaceutical Weights and Measures

Many of the weights and measures used in noblewomens medicinal remedies are imprecise quantities such as a handful or a small cup. In some cases, recipes simply tell the reader to use equal parts of the ingredients. Other recipes, however, rely on more specific weights and measures, as listed below.

Dry Weight

The Nuremberg apothecary measures were used throughout most of the German-speaking territories, with some regional variation. Although all of the terms below appear in noblewomens medical recipes, by far the most common unit of measure was the lot.

Source: Jost Weyer, Graf Wolfgang II. von Hohenlohe und die Alchemie: Alchemistische Studien in Schlo Weikersheim, 15871610 (Sigmarinen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1992), 41012.

Liquid Measure

The most crucial liquid measure in German-speaking regions was the Ma, which was highly variable from region to region but generally ranged from 1.069 to 1.84 liters. A half Ma was often called a Seidel. There were a number of special terms for a quarter Ma, including Quart, Viermelin, Viertel, and Schoppen.

A larger measure used frequently by Dorothea of Mansfeld was the stobgen, i.e., Stbchen, which also varied greatly by region but was generally somewhere between 3 and 5 liters. The Stbchen was specifically a measure for wine, beer, and spirits, but Dorothea used it for large quantities of any liquid.

Source: Hans-Joachim von Alberti, Ma und Gewicht: Geschichtliche und tabellarische Darstellungen von den Anfngen bis zur Gegenwart (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1957), 31731.

Archive Abbreviations

| SHStA Dresden | Schsisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden |

| SLUB Dresden | Schsische Landes- und Universittsbibliothek Dresden |

| HStA Darmstadt | Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt |

| HStA Marburg | Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg |

| UB Heidelberg | Universittsbibliothek Heidelberg |

| HZA Neuenstein | Hohenlohe Zentralarchiv Neuenstein |

| HStA Stuttgart | Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart |

| WLB Stuttgart | Wrttembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart |

Note on Translations

Courtly Germans of the sixteenth century wrote letters to each other using formal and stylized pronouns, which varied depending on the rank and position of the writer and the addressee. When using a scribe, a noble writing to a noble of roughly equal rank used ewere Lieb, Your Dearest, although parents could address their children, and siblings each other, as the less formal deine Lieb. In order to give some sort of differentiation between the formal and the informal pronouns in English, I will use the literal translation, your dearest, for both of these forms but will capitalize in the formal case, Your Dearest. A commoner or a noble of lesser rank writing to a noble of high rank would use alternatively ewer Gnade, Your Grace, or ewer frstliche Gnade, Your Princely Grace; when writing to an elector or electress, he or she could also use ewer kurfrstliche Gnade, literally, Your Electorly Grace. A king or queen was addressed as Your Royal Majesty, Ewer knigliche Majestt, and the Holy Roman Emperor or Empress was Your Imperial Majesty, Ewer kaiserliche Majestt. In the other direction, high-ranking nobles generally addressed patricians (such as physicians and wealthy merchants) and lower-ranked gentry as Euch, a formal form of you, while all other commoners were addressed using du, the most informal you. Referring to themselves, nobles used the royal we (wir) when writing to those of roughly equal or lower rank, including family members, but could use the informal I (ich) when addressing a king or emperor or as a demonstration of special affinity or friendship. Ich was also used when nobles of similar ranks wrote to each other using their own hand rather than a scribe. Commoners always used ich.

Most of the noblewomen presented in this book married at least once, some multiple times, and were therefore known by more than one name. I have attempted to refer to the women as they most commonly appear in the historical sources. In most cases, I refer to noblewomen by their married names, hence Anna of Saxony (not Anna of Denmark), Dorothea of Mansfeld (not Dorothea of Solms), and Sybille of Wrttemberg (not Sybille of Anhalt). However, there are three main exceptions to this rule. Anna of Saxonys daughter Elisabeth will be referred to as Elisabeth of Saxony (rather than Elisabeth of the Palatinate, her married name), and Eleonora of Wrttemberg, who married into the princely house of Anhalt and then into Hesse-Darmstadt, will be referred to by her maiden name as well. Finally, Duchess Elisabeth of Saxony, born a landgravine of Hesse, was known as Elisabeth of Rochlitz by her contemporaries, and I follow that convention here.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).