Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Design of Childhood: How the Material World Shapes Independent Kids

The Dot-Com City: Silicon Valley Urbanism

Writing About Architecture: Mastering the Language of Buildings and Cities

Design Research: The Store That Brought Modern Living to American Homes (with Jane Thompson)

Contents

They look as if they have been dropped by a helicopter flown by a blind pilot, from some giant architectural supermarket in the sky.

ADA LOUISE HUXTABLE, SHLOCKTON GREETS YOU, NEW YORK TIMES , NOVEMBER 23, 1976

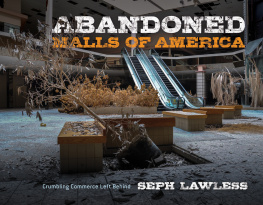

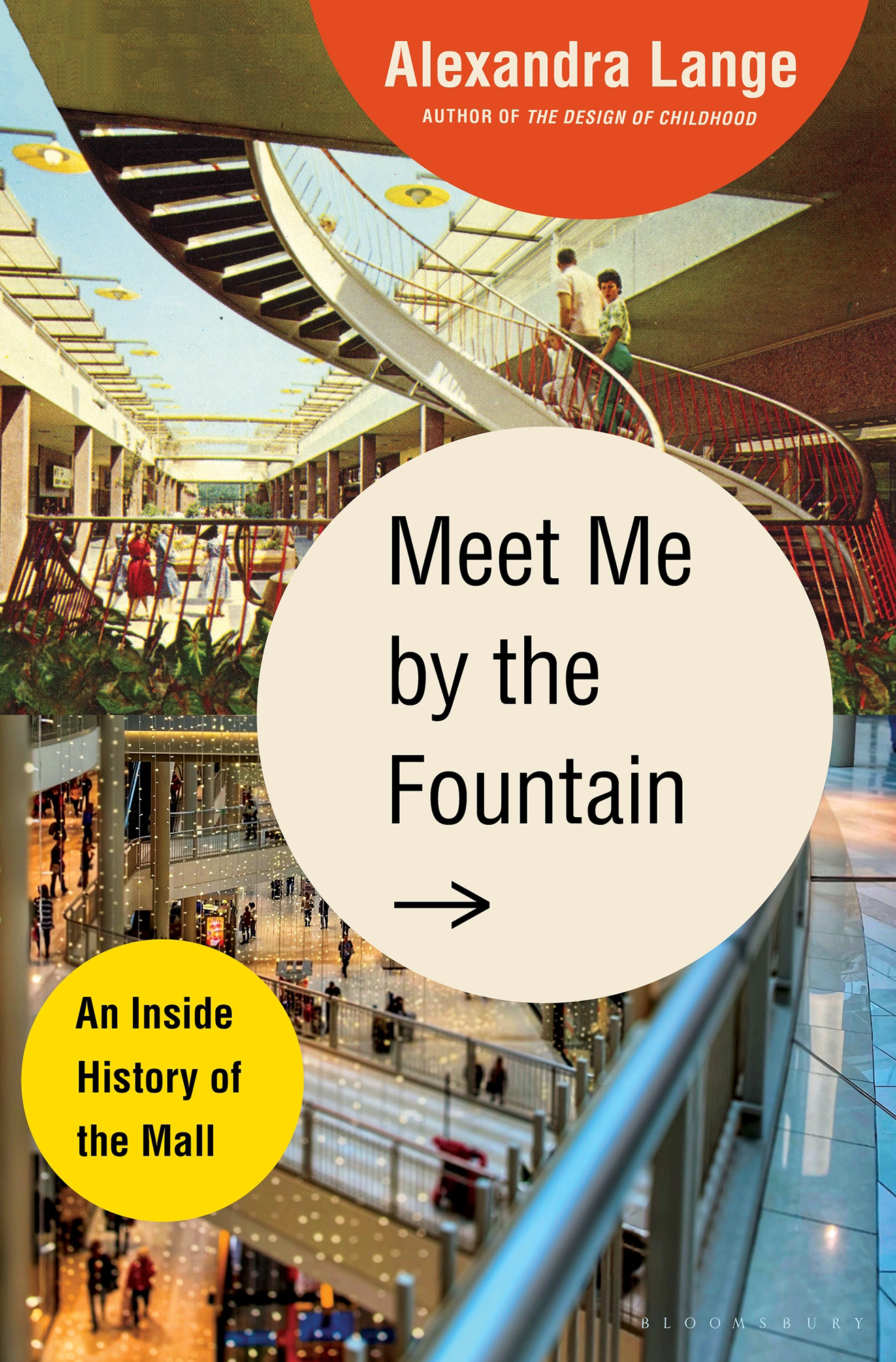

From the turnpike the American Dream was a great gray blob. An earlier version of this mall, then named Meadowlands Xanadu, had worn its tacky heart on its sleeve, its vast expanse a riot of blocks and stripes of color, the patterns dramatizing the precipitous angle of the indoor ski slope as it rose from the parking lot. But now the building reposed glumly on the roadside horizon, less distinct than the green sweep of the Meadowlands or the bowl of MetLife Stadium, home of the New York Giants. Only in one spotthe outward curve of the Nickelodeon roller coasterdid American Dreams facade break its dourness, as if this ride alone could not be contained.

Inside, despite my multiyear study of the history of malls, I found myself lost. Atrium seemed to follow atrium, one with a chandelier, one with a vaulted wood ceiling, one with a plastic garden, without any sense of hierarchy or connection back to the outdoors. Long halls papered with photographs suggested that one day glamorous stores might follow, but the stores that were thereZara, Bath & Body Works, Amazon 4-starwerent anything I needed to leave New York City to visit. Down in the lower level, near the minigolf and aquarium, signs of life: the scent of Auntie Annes, a pastel boba storefront, masked families on their travels to the ski slope, to the indoor beach, to the candy store. After more than a year of quarantine, largely confined to my Brooklyn neighborhood, I found myself touched and thrilled by their linked hands. In May 2021, when it seemed like the summer might bring an end to the Covid-19 pandemic, seeing parents and children out and about having fun together brought me a spike of joy. I wanted to see people, I wanted to watch people, I wanted to be among people. We were all seeking that at the mall.

But as I wandered, pretzel and bubble tea acquired, this joy dropped away. There were just not enough people. Fifteen years in the making, three million square feet in areadeveloped by the same Canadian company that brought indoor pirate ships to Alberta and indoor amusement parks to MinnesotaAmerican Dream felt empty. Beyond that, it felt unmoored. Sure, that was partly due to the pandemic, which closed the mall months after its 2019 opening, bankrupted department stores once slated to be anchor tenants, and made people afraid to gather. But I also felt, at a cellular and architectural level, that this was a mall that had gone too far. Too far from highway to parking lot to atrium. Too far from food to fun to frivolous purchase. While theres an amusement park at the literal heart of the Mall of America, giving visitors the collective thrill of the screamers on the roller coaster, American Dream had me venturing down a long, generic hallway to peer through the fronds of a stick-on palm-leaf decal to glimpse a Japanese-style artificial beach. At their best, malls create community through shared experience (Thrills! Tastes! Tunes!). Their architecture supports that purpose, starting with an ambitious and unmissable fountain that becomes the place to meet. If you asked me to meet you at American Dream, I would have no idea where to go.

The American dreambootstraps, frontier, white picket fencecrossed paths with malls when they emerged in the decades after World War II, as the United States reinvented itself. In 1954, for the first time in American history, the number of children born crossed the four million mark, a level that would be sustained for each of the next ten years. The GI Bill of 1944 and federal highway acts approved in 1944 and 1956 subsidized the growth of the new residential suburbs to house these booming families, and the roads to reach them: more than a million new homes built per year, and more than forty-two thousand miles of highway. What most initial postwar development failed to incorporate, however, was the type of centraland centeringspace that had been part of human civilization since its earliest origins. In subsidizing the home and the road, the government failed to subsidize a place to gather. Something essential to human nature had been missed: People love to be in public with other people. That momentary joy I felt seeing happy families is the core of the malls strength, and the essence of its ongoing utility. In postwar suburban America, the mall was the only structure designed to fill that need. People and money and controversy and larger and larger structures followed. So, in its turn, did the culture. The late twentieth-century United States doesnt make sense without the mall.

American Dream, East Rutherford, New Jersey, Gensler, December 2019. (Photographs by Ross Mantle)

I knew going into this project that I, born in 1973, was part of the Mall Generation, raised on the smell of those pretzels, able to tune out the Muzak and find my car in a multilevel parking garage. As a design critic, as a child of the 1980s, and as a person devoted to the idea that architecture should serve everyone, the mall was my ideal subject. Like design for children, the subject of my last book, the mall was ubiquitous and underexamined and potentially a little bit embarrassing as the object of serious study. Shopping, like children, was a topic for after hours; and malls, like playgrounds, were places dominated by women and children. Go on Etsy and youll find numerous unironic bumper stickers that read A WOMANS PLACE IS IN THE MALL. What I didnt realize was that I had been on the ground for the inception of urban inventions like the festival marketplace at Bostons Faneuil Hall, and that, even in my current Brooklyn neighborhood, I was shopping on a pedestrian street that was one of the citys responses to the flight of white dollars to the suburbs. Once I started looking at shopping not as a distraction but as a shaper of cities, I saw its traces everywhere. While architecture history tended to focus on suburban houses, and planning history looked to the highways, the shopping mall fell into the cracks between the personal and the professional, as if we as a culture didnt want to acknowledge that we needed a wardrobe, furniture, and tools for both.

When I began writing the proposal, I was still nervous, so I mentioned the idea of a book on malls to as many people as I could. Would they be excited? Would they be dismissive?

I was emboldened by the almost universal response: Oh, let me tell you about my mall. In contrast to many other forms of public architecture, which embody fear, power, and knowledge, the mall is personal. People told me about their first jobs, their first piercing, their first boyfriend, their first CD. I found I could sketch the plan of my first mall from memory, down to the placement of the RadioShack. When I emailed an archive for a picture of what was arguably Americas first shopping center, the librarian wrote back with the needed links and added, As a child of the 1990s, Ive got many a fond memory of the mall, including the fad kiosks (pogs, especially). The core of the malls story was architecture, my chosen field, but the personal anecdotes pointed to all the other stories that needed to be told to paint the full picture: urbanism, practicing driving in a deserted lot; identity, collecting Pogs; maturity, going on those teenage dates. Here were hundreds of buildings, connected to everyday life and ordinary people, buildings (as I discovered) that design history had been sidelining for decades.