HOUSE PLANTS

Reaktions Botanical series is the first of its kind, integrating horticultural and botanical writing with a broader account of the cultural and social impact of trees, plants and flowers.

Published

Apple Marcia Reiss

Ash Edward Parker

Bamboo Susanne Lucas

Berries Victoria Dickenson

Birch Anna Lewington

Cactus Dan Torre

Cannabis Chris Duvall

Carnation Twigs Way

Carnivorous Plants Dan Torre

Cherry Constance L. Kirker and Mary Newman

Chrysanthemum Twigs Way

Geranium Kasia Boddy

Grasses Stephen A. Harris

House Plants Mike Maunder

Lily Marcia Reiss

Mulberry Peter Coles

Oak Peter Young

Palm Fred Gray

Pine Laura Mason

Poppy Andrew Lack

Primrose Elizabeth Lawson

Rhododendron Richard Milne

Rose Catherine Horwood

Snowdrop Gail Harland

Sunflowers Stephen A. Harris

Tulip Celia Fisher

Weeds Nina Edwards

Willow Alison Syme

Yew Fred Hageneder

HOUSE PLANTS

Mike Maunder

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2022

Copyright Mike Maunder 2022

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789145441

Contents

The relationship between people and house plants is both ancient and intimate, as seen in this 15th-century illustration of a bedroom with potted plant, from Der Trojanische Krieg (1455).

Introduction

Plants of the Indoor Biome

The chief end of labor should be human happiness, and so the effort that is put forth in the cultural art of houseplants not only brings happiness to the heart of the grower, but also to the passer-by who with a hungry soul admires this plant.

HUGH FINDLAY, 1916

T his is an exploration of an apparently mundane group of plants, the house plant. Like the relationship we have with edible and medicinal plants, our bond with house plants is an intimate botanical relationship; after all, we choose to bring them into our homes. Whether a thriving and diverse collection loved by its owner, or a chlorotic embarrassment, house plants tell a complex story about how we live, why we need nature and how we take wild things and domesticate them.

Much has been written about plant blindness, peoples seeming ability to overlook and undervalue plants, to the extent that vital subjects such as crop diversity and plant conservation are profoundly under-resourced. However, the fact that house plants exist, are bought by the million and bring joy to many suggests that a large proportion of our species is not plant blind, and that is a very good thing.

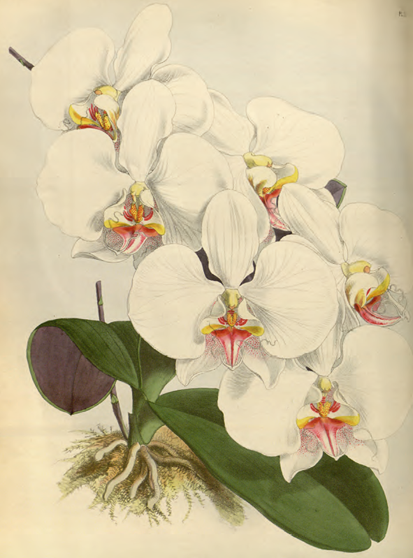

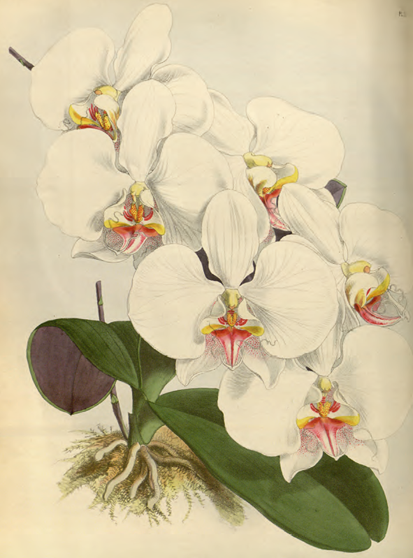

Our love for house plants opens a door to exploring important stories about plant domestication and perhaps ultimately about the mutualism between plants and people. Some house plants exist unmodified, almost as they were when collected from the wild, for instance the spectacular Swiss cheese plant, Monstera deliciosa. Others, such as those ultimate house plants the African violet, Saintpaulia, and the moth orchid, Phalaenopsis, have been profoundly altered by breeders over many decades, and tell a story of domestication, in which art and science have worked together.

Perhaps the ultimate house plant, the African violet was changed profoundly by a century of breeding. Illustration from Curtiss Botanical Magazine, vol. CXXI (1895).

We are becoming an urban species, and more of our existence than ever is spent indoors insulated from nature and living in an increasingly impersonal world. Fewer people have gardens, and those who rent a property tend not to invest their time in cultivating a garden. At the same time, we are told we possess a deep relationship with nature that is essential for our well-being. The naturalist and benign manifestation of biophilia is our desire to share those new domesticated landscapes, specifically our homes, with a favoured selection of plant species, chosen for pleasure and companionship. The house plant is part of our innate need for novelty, a flicker of green life in an increasingly homogeneous world.

An investment in science changed the moth orchid, Phalaenopsis, from expensive luxury to supermarket commodity. Illustration by John Nugent Fitch from Robert Warner and Benjamin S. Williams, The Orchid Album, vol. I (1882).

The nomenclature of house plants is necessarily vague: they can be referred to as indoor plants, pot plants, foliage plants or house plants. The term house plant was coined in 1952 by the English nurseryman Thomas Rochford, whose stock of ornamental plants for the house had previously been called green plants or foliage plants.

House plants are usually tropical or subtropical in origin (although in the UK the common ivy, Hedera helix, remains a favourite), rooted and potted, intended as adornments for the home, and often purchased to endorse an individuals cultural and social identity. A house plant in London may be a garden plant in Spain or Florida. In the tropics you have the strange situation where a tropical monstera may grace an air-conditioned living room while outside the window the same species is scrambling up a tree as a robust fruiting vine. There is a shady and flexible line between the house plant and the conservatory plant, and a narrow gradient between the house plant as benign decoration and the house plant as focus for obsession. There is also a fine thread between cut flowers and house plants; a pot of poinsettia, Euphorbia pulcherrima, bought for Christmas is in reality a rooted bunch of cuttings that will likely be thrown away after a few months. Similarly, the bound and braided rooted cuttings of Dracaena sanderiana that are sold in containers often without soil (ironically known as lucky bamboo) rarely survive long. For this book the definition has been kept loose and flexible, allowing for a reasonable amount of meandering.