Foreword

by Sir Robin Knox-Johnston

N o one in their right mind goes to sea to encounter heavy weather. But those who make longer voyages are likely to experience bad weather at some time because it cannot be avoided all the time. It is in these situations that our seamanship is tested and this is not a test we can afford to fail, so thought and preparation for bad weather are an integral part of the preparation for a voyage offshore or across an ocean.

The preparations start with knowing your boat. Even boats from the same mould will behave differently if their stores and equipment have been placed in different places, and it is getting to understand how your boat behaves in different circumstances that are fundamental to survival in heavy weather. We say that the essence of good seamanship is safety, and safety begins with knowing your boat. The next most important issue is preparation. This applies both to the boat and the crew. Sit inside the boat and imagine it on its side. What might shift at that angle? Well, ensure that it cannot. Can I still find the items I might need quickly? Well, if not, plan where you will put them so you can find them in a hurry.

Crew preparation is paramount. You cannot deal with emergencies unless the crew also know how to respond. Make sure they know where everything is stowed, how to reef at night in a bucking boat and of course, how to set the last resort, the storm sails. Above all, exercise them with man overboard procedures and ensure they know where all the safety equipment is stowed and how to use it.

Many organisations still insist on storm trysails with a separate track on the mast. Forget it. Very few of us who go solo ocean racing bother with them as they are difficult to set up and hoist. Have the mainsail made with a deep fourth reef which reduces its size to that of the trysail. It does not require all that fumbling on a pitching deck, probably in the dark, putting slides on a track, and is much easier to set. In more than 55 years of sailing I have never owned a trysail but I have always had that fourth reef in my mainsails, and it has been used very effectively and necessarily on a number of occasions.

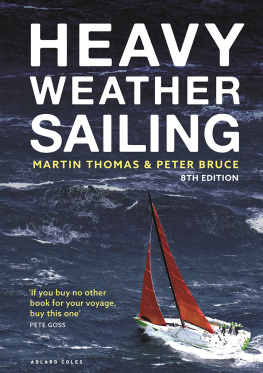

If bad weather is forecast, charge up the batteries. They will be needed to restart the engine and keep the electronics working. Watch the wind and the waves because that will dictate how you might manage the boat in large breaking waves. One of the worst scenarios is a cross sea, where the waves have built up from one direction and the wind has changed and now other waves are coming from a different angle. This is an especially dire situation because you can get the yacht to lie to one set of waves but the other set, coming in from the beam, will be the one that smashes into the boat. How to deal with that? Well, we all have different experiences and you have to work out what will be best for you and your boat. The ideas recounted in Heavy Weather Sailing are likely to provide the answer. When a boat is handled with knowledge and thought she should come through without damage.

When I went around the world in the 9.8m (32ft) Suhaili, the only literature in existence that gave an indication of what a storm in the Southern Ocean could be like was that of the Smeetons in Tzu Hang. They were pitchpoled in a larger boat. I had to experiment as to how I could hold Suhaili so she would not rush down the front of 80-foot (24.3m) waves when the rudder has little effect, and prevent her swinging across the front of the wave when she would have been almost bound to be have been rolled and dismasted. I found that 220m (720ft) of 5cm (2in) circumference rope, paid out as a bight, held Suhailis stern to the waves and that was when I could get my best sleep because I knew that, as she started her downhill rush, the warp would check her speed before she went out of control. That worked for Suhaili, but would not necessarily work for another boat. When I participated in the Velux5oceans race 37 years later the boat, a 60-footer (18.3m), was fast enough to keep ahead of the waves. Well, most of the time!

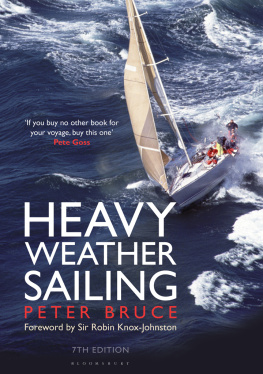

Heavy Weather Sailing is a classic. It gives examples of handling bad weather from many different experiences in very different yachts. You will find that all the matters Ive raised here feature within its pages, including a carefully considered treatise on the subject of whether to use a trysail or a fourth reef. The book cannot tell you how to handle every circumstance you might find yourself in, but it does give you a wealth of advice and examples of how others have managed, that can help you find what is best for you. We often talk about essential reading, but for anyone contemplating a longer voyage, with land and a safe haven over the horizon, then reading other peoples experiences is an essential part of preparation. Heavy Weather Sailing gives this with great care and relevance.

Preface

A dlard Coles OBE died in 1985. He left behind him a multitude of friends and admirers, many of whom knew him only through his books. Apart from his ability to write vividly and clearly, Adlard was an extraordinary man. In spite of being a diabetic, a quiet and very gentle person with something of a poets eye, he was incredibly tough, courageous and determined. Thus it was very often that Adlards Cohoe appeared at the top of the lists after a really stormy race. When reading Adlards enchanting prose one also needs to take into account that he was supremely modest, and his scant reference to some major achievement belies the effort that must have been required. It is clear that Adlard minimised everything, which does him credit. As an example, the wind strengths he gave in his own accounts in the earlier editions of Heavy Weather Sailing were manifestly objective and warrant no risk of being accused of exaggeration for narrative effect.

There were three editions of Heavy Weather Sailing undertaken by Adlard Coles and this new edition of Heavy Weather Sailing is my fourth, and brings the total number of editions to 7 over a span of 50 years. In writing about a subject that most people do their best to avoid, it should be remembered that to have successfully sailed through a particularly violent storm gives a sailor confidence at sea as nothing else will. Adlard Coles lightly referred to the collection of storms that he endured as being like trophies of a big game hunter, but they are educational and character forming too. After a big storm it will be easier to judge how much a boat and crew can endure before they break, and what the warning signs are.

The ethos of this book is to supply the specialist information that will prepare a sailor for heavy weather, and give honest examples of what happened to people and their vessels that have encountered a severe storm. Most space has been given to the specialist information the expert advice as this provides a platform of knowledge to enable the reader to be able to glean the maximum from the storm experiences that follow, and the principles to employ when bad weather approaches. These storm experiences have been carefully picked to cover a wide range of predicaments. They tend to relate to unusually high wind strengths because these rare extreme conditions best prove the worth of a particular course of action. They also illustrate how modern heavy weather seamanship has been able to evolve with the benefit of improved knowledge, clothing, design and materials. The improved knowledge is the most important factor, of course, and the contributors of these accounts have freely given of their experience to help others who may follow in their wake.

Next page