Wabi-Sabi

The Japanese Philosophy Of Accepting Imperfection And Taking Pleasure In The Transient Nature Of Earthly Things

Alicia Mori

Copyright 2019 by Alicia Mori

All rights reserved.

This document is geared towards providing exact and reliable information with regards to the topic and issue covered. The publication is sold with the idea that the publisher is not required to render accounting, officially permitted, or otherwise, qualified services. If advice is necessary, legal or professional, a practiced individual in the profession should be ordered.

From a Declaration of Principles which was accepted and approved equally by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations.

In no way is it legal to reproduce, duplicate, or transmit any part of this document in either electronic means or in printed format. Recording of this publication is strictly prohibited and any storage of this document is not allowed unless with written permission from the publisher. All rights reserved.

The information provided herein is stated to be truthful and consistent, in that any liability, in terms of inattention or otherwise, by any usage or abuse of any policies, processes, or directions contained within is the solitary and utter responsibility of the recipient reader. Under no circumstances will any legal responsibility or blame be held against the publisher for any reparation, damages, or monetary loss due to the information herein, either directly or indirectly.

Respective authors own all copyrights not held by the publisher.

The information herein is offered for informational purposes solely, and is universal as so. The presentation of the information is without contract or any type of guarantee assurance.

The trademarks that are used are without any consent, and the publication of the trademark is without permission or backing by the trademark owner. All trademarks and brands within this book are for clarifying purposes only and are the owned by the owners themselves, not affiliated with this document

Table of Contents

CHAPTER ONE

What Is Wabi-Sabi?

A

ccording to Japanese legend, a young guy called Sen no Rikyu hunted to find out the elaborate set of habits referred to as the way of tea. He went to tea-master Takeeno Joo, who taught the younger man by asking him to tend the garden. Rikyu cleaned debris up and raked the floor until it was ideal, then inspected the pristine garden. Before introducing his job to the master, he left a cherry tree, causing a few blossoms to spill randomly on the floor.

Emerging from the 15th century as a response to the prevailing aesthetic of lavishness, ornamentation, and rich substances, Wabi-Sabi is the art of finding beauty in imperfection and profundity in earthiness. Back in Japan, the idea is so deeply ingrained that it is hard to describe to westerners; no immediate translation captures it all.

Broadly, Wabi-Sabi is all that todays glossy, mass-produced, technology-saturated culture is not. It is flea markets, not shopping malls; outdated timber, not swank flooring coverings; just one-morning decoration, not a dozen of red roses. Wabi-Sabi knows the tender, raw splendor of a gray December landscape along with the aching elegance of a deserted building or fallen trees. It celebrates blemishes cracks and rust and the rest of the symbols that weather and time leaves behind. To discover Wabi-Sabi would be to observe that the magnificent beauty in something which may initially look decrepit and nasty.

Wabi-Sabi reminds us that were transient beings on this world that our bodies, in addition to the material world around us, are in the process of returning to dust. Natures cycles of growth, corrosion, and erosion have been embodied in frayed edges, rust, and liver spots. During Wabi-Sabi, we know how best to adopt the glory and the depression found in such passing moments.

Obtaining Wabi-Sabi in your life does not require cash, instruction, or special abilities. It requires a mind quiet enough to love muted beauty, courage to not fear bareness, openness to take things as they are with no objection. Its dependent upon the capability to slow down, to change the equilibrium from planning to doing, to enjoying instead of simply engaging.

You may spark your admiration of Wabi-Sabi using one thing from the back of a cupboard: a broken vase or even a faded piece of fabric. Look profoundly for the minute details that gives it character; study it with your own hands. You do not need to know why you are attracted to it, but you really do need to appreciate it because of the beauty that it is.

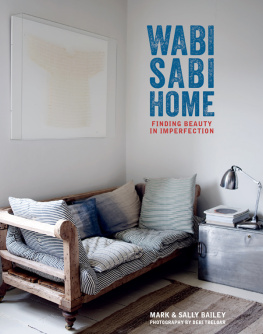

Rough textures, minimally processed products, natural substances, and subtle colors are Wabi-Sabi. Think about the musty-oily scene which lingers around an early wooden jar or the mystery behind a tarnished goblet. These tarnishes conveys an energy which the glow of a new thing does not possess. Our universal longing for wisdom, for genuineness, for shared background, manifests in such matters.

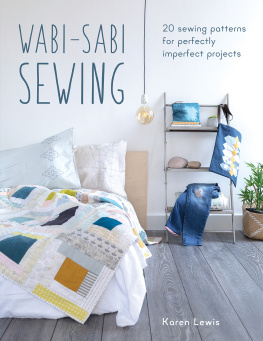

There is no wrong or right way to make a Wabi-Sabi house. It can be simple as having an old bowl for a container for your days mail, accepting the paint in an old chair, or going into the backyard to do some planting. Whatever it is, it cannot be purchased. Wabi-Sabi is a frame of mind, a way of becoming. It is the subtle art of being at peace with your own environment.

Wabi-Sabi is an ancient Japanese philosophy centered on accepting the transient nature of life. It is rooted in Buddhism and originated out of tea ceremonies where precious utensils were handmade, imperfect, and irregular. Theres not any direct western interpretation for Wabi-Sabi. It is basically the art of finding beauty in the imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.

Wabi-Sabi is a Japanese doctrine frequently described as enjoying the beauty of imperfection. While refining Wabi-Sabi to one definition or translation does not do justice to its own nuances and fluidity, the wide theories connected with it are impermanence and imperfection. For your understanding, Wabi-Sabi nurtures everything by admitting three easy truths:

- nothing lasts,

- nothing has been completed, and

- nothing else is perfect.

In Japanese, the meanings and connotations of both Wabi and Sabi have evolved over time. Wabi was associated with a particular sort of solitude and isolation, almost similar with someone living in distant nature might experience. Sabi was linked with withering, rusting, tarnishingthe normal progression of all things. However, as Japanese culture became more obsessed with the elaborate, an opposing school of thought arose from the 14th century. Loneliness and isolation have been regarded as shrewd and liberating, as well as the imperfections caused by the natural development of things. It should be gathered that impermanence of life is the best principle to be adopted.

The course of Wabi-Sabi

Wabi-Sabi is often associated with a sense of peace, together with the natural development of life. Maintaining that life and the understanding that things are impermanent, enables us to love the beauty and sadness of it. Therefore, a wooden table which is dated over the years might appear ugly and unpleasant to look at. Finding Wabi-Sabi will require you to observe the beauty of imperfection and transience. Even though Wabi-Sabi is frequently regarded as an aesthetic doctrine, it teaches us more; such as:

- rather than focusing on what might be, Wabi-Sabi concentrates on appreciating whats the normal, incomplete and old.

- suffering pain, the ugliness of life, are like the joys of a classic table. Theyre a natural part of life which needs approval and admiration.

Next page