George Monbiot - Regenesis

Here you can read online George Monbiot - Regenesis full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2022, publisher: Penguin Books Ltd, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

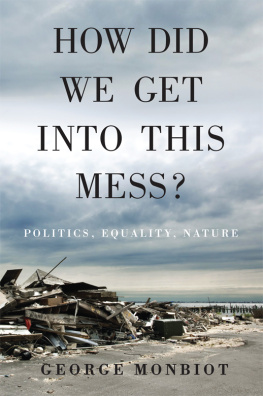

- Book:Regenesis

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Books Ltd

- Genre:

- Year:2022

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Regenesis: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Regenesis" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Regenesis — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Regenesis" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

George Monbiot is an author, Guardian columnist and environmental campaigner. His best-selling books include Feral: Rewilding the Land, Sea and Human Life and Heat: How We Can Stop the Planet Burning; his latest is Regenesis: Feeding the World without Devouring the Planet. George cowrote the concept album Breaking the Spell of Loneliness with musician Ewan McLennan, and has made a number of viral videos. One of them, adapted from his 2013 TED talk, How Wolves Change Rivers, has been viewed on YouTube over 40 million times. Another, on Natural Climate Solutions, which he co-presented with Greta Thunberg, has been watched over 60 million times

To my brilliant assistant Fi,

without whom it would all have been impossible

In researching and writing this book, I have relied to a greater extent than ever before on the generosity of other people, who have given me their time, advice and expertise, made space for me, and put up with me during the intense and unrelenting work the project required.

Thank you above all to my wonderful family: my partner Rebecca and my daughters Hanna and Martha. Thanks too to my fantastic assistant Fiona Rowe, to Katie Kedward and Charlie Young, whose research work during the scoping phase was invaluable, and to Jo Haward, whose work on the references was so fast and efficient.

Thank you especially to my genius of an editor, Chloe Currens, whose insight, vision, and great attention and care have immeasurably improved this book. Thank you to my brilliant agent Antony Harwood, to the excellent and unfailingly accurate copy-editor Richard Mason, and to the rest of the team at Penguin.

Thank you to the farmers, practitioners and researchers I followed, who were so patient and kind, as I took up their time and asked annoying questions: Iain Tolhurst (Tolly), Tamara and Gena, Tim Ashton, Ian Wilkinson and FarmEd, Fran Gardner, Simon Jeffrey, Paul Cawood, Pasi Vainikka and Solar Foods, FareShare and SOFEA, Stephen Marsh-Smith, Alison Caffyn and Christine Hugh-Jones, Rachel Stroer and the Land Institute, Bruce Friedrich, Maia Keerie and Sophie Armour of the Good Food Institute. Thank you to Alexandra Elbakyan and Sci-Hub, without whom much of the research material I needed would have been unobtainable: access to knowledge is not a crime.

My great thanks to the expert reviewers, who so generously gave their time to read my manuscript, make comments and suggestions, and show me where I was going wrong: Tim Benton, Hannah Ritchie, Tara Garnett, Mary Stockdale, Aislinn Pearson, Chloe MacLaren, Dan Blumgart, Tim Lenton, Jamie Arbib, Vicki Hird, Erik Meijaard, Tomas Linder, Simon Fairlie, Frank Ashwood, Franciska de Vries, Sarah Wakefield and John Boardman. All the remaining mistakes are mine.

Many thanks too to my loving and inspiring sister Eleanor, to Mark Lynas, Joel Scott-Halkes and Tong Wu, to my fellow orchardists Hugh Warwick, Zoe Broughton, Kate Raworth, Roman Krznaric, Caspar Henderson, Cristina Mateos, Phil Mann and Amanda Smigelski-Mann, to Stewart Young, the East Ward Allotment Association, Steve Farmer, Jim Mallinson, Michael Witzel, Anna Morser, to Peter Gauvain, Clem Cheetham and Nick Metcalfe on the Apocalypse Cow team, and to Franny Armstrong, Nicola Cutcher and the rest of the scurvy crew on Rivercide, to my long-suffering editors at the Guardian, Damian Carrington, Nigel Dudley, Mike Mason, Jeremy Lent, Simon Evans, Ben Middleton, Andrew Balmford, Stuart Pengs, David Butler, Jim Thomas, the Soil Association, Piero Visconti, Duncan Cameron, Alexandra Sexton, Charles Ssekyewa and Gunnar Rundgren.

Its a wonderful place for an orchard, but a terrible place for growing fruit. In central England, far from the buffering effect of the sea, the trees are blighted by late frosts. Freezing air flows like water, but here, on this flat plot, dammed by rows of houses, it gathers and pools, drowning the orchard in cold.

Every year, as the trees come into blossom, my hopes crack open with the breaking buds. Roughly two years out of three, they wither with the flowers. Frost curls into the branches like poison gas, shrivelling and blackening the stamens.

By autumn, the orchard is a living graph of spring temperatures. Apple varieties blossom at different but regular dates. Unless a freeze is especially hard, it damages only the open flower. From the trees with and without fruit, you can tell when the frost struck, almost to the night.

Every variety belongs to the same species: Malus domestica, which translates literally as tamed evil. The reasons for the age-old defamation of a lovely tree are complex, but one is likely to be etymological confusion: a dialect name for fruit , or malon appears to have slipped from Greek into Latin, where it was, so to speak, corrupted: into malum, or evil.

This single species, too good to be true, has been bred into thousands of different forms: dessert apples, cooking apples, cider apples, drying apples, in an astonishing range of sizes, shapes, colours, scents and flavours. We grow Millers Seedling, which ripens in August and must be eaten from the tree, as the slightest jolt in transit bruises its translucent skin. It is sweet and soft, more juice than flesh. By contrast, the Wyken Pippin, hard as wood when picked, is scarcely edible till January, then stays crisp until the following May. We grow St Edmunds Pippin, which has skin like sandpaper and is dry and nutty and aromatic for two weeks in September, after which it turns to fluff, and the Golden Russet, whose taste and texture are almost identical, but only in February. The Ashmeads Kernel, crunchy, with a hint of carraway, my favourite apple, peaks in midwinter. The Reverend W. Wilks puffs up like wool when you bake it, and tastes like a smooth white wine. The Catshead, roasted at Christmas, is almost indistinguishable from mango pure. Ribston Pippin, Manningtons Pearmain, Kingston Black, Cottenham Seedling, DArcy Spice, Belle de Boskoop, Ellis Bitter: these fruit are capsules of time and place, culture and nature.

As every tree requires subtly different conditions to prosper, some do better here than others. Some varieties are so finely adapted to their place of origin that they perform disappointingly on the other side of the same hill. By choosing breeds that blossom at different times, we have sought in this orchard to spread the risk. Even so, in bad years, when frost strikes repeatedly, we lose almost everything.

But yes, despite the many broken dreams, its a wonderful place for an orchard. When I arrived this morning, its beauty made me gasp. The first apple trees have come into flower: the pink buds uncurling to reveal their pale hearts. The pear and cherry trees are in full sail, carrying so much white blossom that their branches lift slightly in the breeze.

I walk the rows of trees, smelling them. Every variety has a different, faint scent: some of the blooms smell like hyacinth, some like lilac, some like

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Regenesis»

Look at similar books to Regenesis. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Regenesis and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.