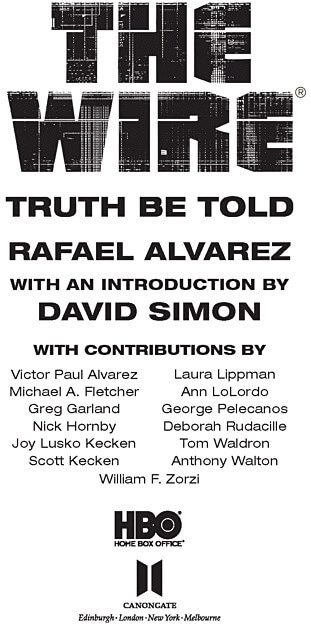

Rafael Alvarez - The Wire

Here you can read online Rafael Alvarez - The Wire full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: Canongate Books, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Wire

- Author:

- Publisher:Canongate Books

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Wire: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Wire" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Wire — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Wire" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

by David Simon

Were building something here and all the pieces matter.

DETECTIVE LESTER FREAMON

Swear to God, it was never a cop show. And though there were cops and gangsters aplenty, it was never entirely appropriate to classify it as a crime story, though the spine of every season was certain to be a police investigation in Baltimore, Maryland.

But to say so nearly a decade ago, back when The Wire first premiered on HBO, would have been to invite certain ridicule. It would have sounded comically pretentious to have invoked Lester Freamons claim.

As a medium for serious storytelling, television has precious little to recommend it or at least that has been the case for most of its history. What else can we expect from a framework in which the most pregnant moment in the story has for decades been the commercial break, that five-times-an-hour pause when writers, actors, and directors are required to juke the tale enough so that a trip to the refrigerator or bathroom does not mean a walk away from the television set, or, worse yet, a click on the remote to another channel.

In such a construct, where does a storyteller put any serious ambition? Where are the tales to reside safely and securely, but in the simplest paradigms of good and evil, of heroes, villains, and simplified characterization? Where but in plotlines that remain accessible to the most ignorant or indifferent viewers. Where but in the half-assed, dont-rattle-their-cages uselessness of self-affirming, self-assuring narratives that comfort the American comfortable, and ignore the American afflicted; the better to sell Ford trucks and fast food, beer and athletic shoes, iPods and feminine hygiene products.

Consider that for generations now the cathode-ray glow of our national campfire, the televised reflection of the American experience and, by extension, that of the Western free-market democracies has come down to us from on high. Westerns and police procedurals and legal dramas, soap operas and situation comedies all of it conceived in Los Angeles and New York by industry professionals, then shaped by corporate entities to calm and soothe as many viewers as possible, priming them with the idea that their future is better and brighter than it actually is, that the time is never more right to buy and consume.

Until recently, all of television has been about selling. Not selling story, of course, but selling the intermissions to that story. And therefore little programming that might interfere with the mission of reassuring viewers as to their God-given status as indebted consumers has ever been broadcast and certainly nothing in the form of a continuing series. For half a century, network television wrapped its programs around the advertising not the other way around, as it may have seemed to some.

This is not to deny that HBO is a large and profitable piece of Time Warner, which itself is a paragon of Wall Street monolith. The Wire s 35mm misadventure in Baltimore for any of its claims to iconoclasm is nonetheless sponsored by a media conglomerate with an absolute interest in selling to consumers. And yet, on that conglomerates premium cable cannel, the only product being sold is the programming itself. In that distinction, there is all the difference.

Beginning with Oz and culminating in The Sopranos , the best work on HBO expresses nothing less than the vision of individual writers, as expressed through the talents of directors, actors, and film crews. For a rare window in the history of television, nothing much gets in the way of that. Story is all.

If you laughed, you laughed. If you cried, you cried. And if you thought and there is actually no prohibition on such merely because you had a TV remote in your hand then you thought. And if you decided, at any point as many an early viewer of The Wire did to change the channel, then so be it. But on HBO, nothing other than the stories themselves was for sale and therefore absent the Ford trucks and athletic shoes there is nothing to mitigate against a sad story, an angry story, a subversive story, a disturbing story.

The first thing we had to do was teach folks to watch television in a different way, to slow themselves down and pay attention, to immerse themselves in a way that the medium had long ago ceased to demand.

And we had to do this, problematically enough, using a genre and its tropes that for decades have been accepted as basic, obvious storytelling terrain. The crime story long ago became a central archetype of our culture, and the labyrinth of the inner city has largely replaced the spare, unforgiving landscape of the American West as the central stage for our morality plays. The best crime shows Homicide and NYPD Blue , or their predecessors, Dragnet and Police Story were essentially about good and evil. Justice, revenge, betrayal, redemption there isnt much left in the tangle between right and wrong that hasnt been fully, even brilliantly explored by the likes of Friday and Pembleton and Sipowicz.

By contrast, The Wire had ambitions elsewhere. Specifically, we were bored with good and evil. To the greatest possible extent, we were quick to renounce the theme.

After all, with the exception of saints and sociopaths, few in this world are anything but a confused and corrupted combination of personal motivations, most of them selfish, some of them hilarious. Character is essential for all good drama, and plotting is just as fundamental. But ultimately, the storytelling that speaks to our current condition, that grapples with the basic realities and contradictions of our immediate world these are stories that, in the end, have some chance of presenting a social, and even political, argument. And to be honest, The Wire was not merely trying to tell a good story or two. We were very much trying to pick a fight.

To that end, The Wire was not about Jimmy McNulty. Or Avon Barksdale. Or Marlo Stanfield, or Tommy Carcetti or Gus Haynes. It was not about crime. Or punishment. Or the drug war. Or politics. Or race. Or education, labor relations or journalism.

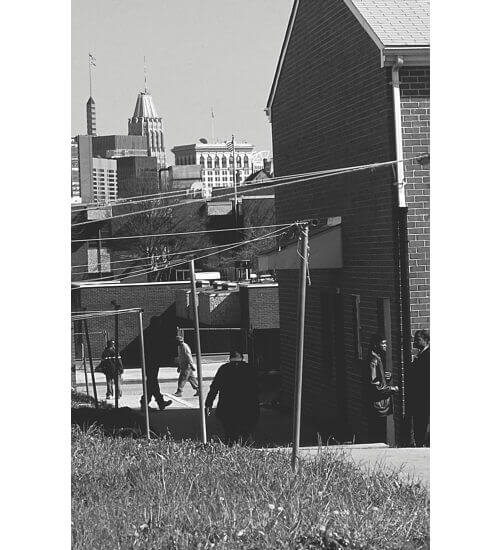

It was about The City.

It is how we in the West live at the millennium, an urbanized species compacted together, sharing a common love, awe, and fear of what we have rendered not only in Baltimore or St. Louis or Chicago, but in Manchester or Amsterdam or Mexico City as well. At best, our metropolises are the ultimate aspiration of community, the repository for every myth and hope of people clinging to the sides of the pyramid that is capitalism. At worst, our cities or those places in our cities where most of us fear to tread are vessels for the darkest contradictions and most brutal competitions that underlie the way we actually live together, or fail to live together.

Mythology is important, essential even, to a national psyche. And Americans in particular are desperate in their pursuit of national myth. This is understandable, to a point: coating an elemental truth with the bright gloss of heroism and national sacrifice is the prerogative of the nation-state. But to carry the same lies forward, generation after generation, so that our collective sense of the American experiment is better and more comforting than it ought to be this is where mythology has its cost, and a cost not only to the United States but to the world as a whole. In a young and struggling nation, a moderate degree of self-elevating bullshit has a certain earnest charm. For a militarized, technological superpower overextended in both its economic and foreign policy impulses it begins to approach the Orwellian.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Wire»

Look at similar books to The Wire. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Wire and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.