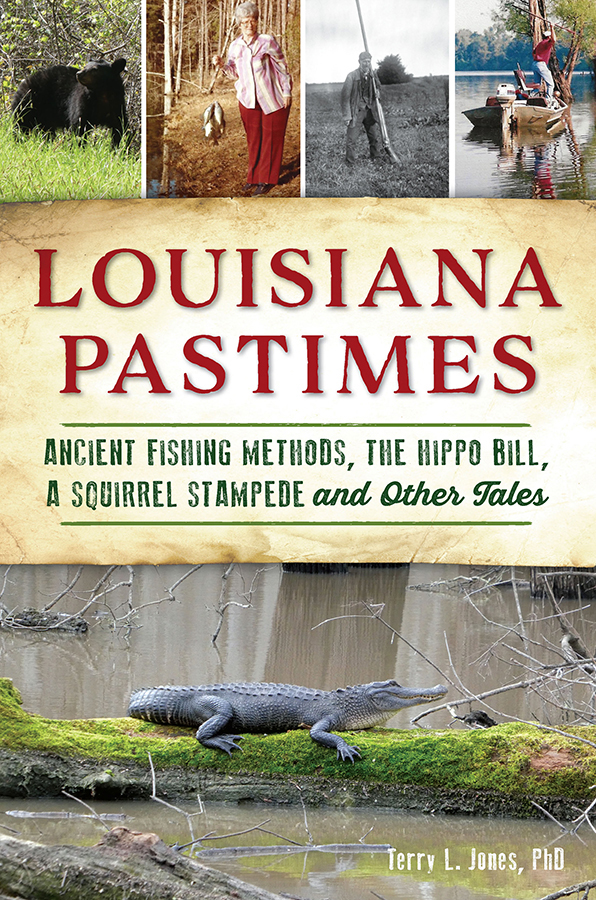

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Terry L. Jones, PhD

All rights reserved

Front cover, top, left to right: authors collection; authors collection; Free-Images. com; authors collection; bottom: authors collection.

First published 2020

E-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43966.934.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019954261

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.584.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To Carol, for putting up with me for forty-three yearsCONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Two of my passions are studying Louisiana history and enjoying the great outdoors. I was a Louisiana history professor at the University of Louisiana at Monroe for twenty-five years, and I have spent sixty years hunting, fishing and exploring the Bayou States woods and waterways.

I also enjoy writing about my interests and have published five books on Louisiana history, including The Louisiana Journey (Gibbs Smith, 2007), a popular textbook that was adopted by many of the states school systems. After enjoying success in the field of history, I became an outdoors writer so I could share my love of hunting and fishing with others.

In 2015, I decided to combine my two passions by writing a monthly column that would focus on Louisiana history and outdoor recreation. Having difficulty in coming up with a title for the column, I asked my wife, Carol, to brainstorm with me, and she suggested Pastimes. I liked it because the column was going to focus on both past events and leisurely activity. Pastimes was launched and has been enjoyed by the readers of such publications as the Ouachita Citizen, Country Roads Magazine, Piney Woods Journal, Concordia Sentinel, Louisiana Road Trips, Amite Tangi Digest, St. Charles Herald Guide and the New Era Leader.

The column covers a variety of topics. Some are historical in nature, such as articles on the early exploration of Louisiana, hunting and fishing techniques used by Native Americans and important historic events. Others are based on my personal experiences, including what Carol calls Terry Moments, or the myriad mishaps that befall me in the outdoors. And there are some articles that are just quirky, such as a two-part story on evidence of Bigfoot in Louisiana, sightings of sea serpents in the Gulf of Mexico and strange things that have reportedly fallen from the sky.

This eclectic mix of topics has proven popular with both readers and my professional peers. The Louisiana Outdoor Writers Association has bestowed its Excellence in Craft Award on several of the articles: The Chase Hunters (about the lucrative hunting profession during colonial times), The Wild Girl of Catahoula (concerning a mysterious feral woman who terrorized central Louisiana in the late nineteenth century) and The Great Deer Comeback (a story on the successful postWorld War II deer restocking program, which in this book is titled Deer Hunting Evolution). I am also quite proud that another article, A Shortage of Women, was included in Ric Baker and Vivian Richard Beitmans college-level critical-thinking textbook, Critical Approaches to Reading, Writing and Thinking (Kendall Hunt, 2019).

Now, thanks to Arcadia Press, I am able to publish the first fifty Pastimes articles in book form. A number of people have made this possible, and I would like to express my gratitude for their help. Joe Gartrell, Arcadia Press acquisitions editor, guided me through the publishing process, and Rick Delaneys editing improved the manuscript. Patricia A. Threatt of McNeese State Universitys Frazar Memorial Library provided the Louisiana Maneuvers photo; Valerie Feathers of the Louisiana Division of Archaeology provided images from the divisions collection; and Etta Gwynne Shively Smith allowed me to use the photograph of the Shively family preparing for a deer hunt. Thank you all.

NOTHING NEW UNDER THE SUN

The Natchitoches area has long been a popular destination for tourists and sportsmen. One visitor from France was especially intrigued at how the local people used trotlines to catch catfish.

The trotlines were, he wrote, no more than fishing lines about [thirty-six feet] long. All along these lines, numerous other lines are tied about a foot apart. At the end of each line is a fish hook on which they put a bit of dough or a small piece of meat. With this method they do not fail to catch fish weighing more than fifteen or twenty pounds.

The tourist was Andr Pnicaut, and he visited Natchitoches three hundred years ago. His journal reminds us that many of our modern fishing techniques were actually developed by Indians long ago. The Indians methods of taking fish were as varied as they were ingenious and would be recognized by any fisherman today.

Hooks and lines were popular, with hooks being made from bone or deer antler and line from deer sinew. Archaeologists have found three-thousand-year-old tear-shaped, polished stones with holes or grooves in the top that are believed to have been weights for nets or trotlines.

The Chitimacha of South Louisiana used wooden slat traps and gill and hoop nets. The latter were made from rabbit vine and were attached to round wooden frames and placed at the mouths of bayous.

The Chitimachas favorite fishing technique was to swim underwater with small nets made from hemp. These nets were about three feet long and three feet in diameter and had elastic green cane fixed on each side to serve as a spring.

Some modern fishermen continue to practice the old tactic of gigging, or spearing, fish. Authors collection.

A number of men lined abreast across a long pond and then swam underwater, keeping their nets open in front of them by pulling the green cane back with both hands. The men stayed underwater until they either ran out of breath or their nets were full of fish. When the nets were full, they let go of the cane, and it sprang shut to close the opening.

One Frenchman who participated in this type of fishing wrote: I have been engaged half a day at a timeand half drowned in the diversion when any of us was so unfortunate as to catch water snakes in our sweep, and emptied them ashore, we had the ranting voice of our friendly posse comitatus, whooping against us, till another party was so unlucky as to meet with the like misfortune. During this exercise, the women are fishing ashore with coarse baskets, to catch the fish that escaped our nets.

Spearing fish with harpoons or bows and arrows was also quite effective, with Indians sometimes using torches to hunt at night. Harpoon shafts were usually made from ash, cypress or willow because they float. When a hit was made, the fish quickly became tired from dragging the buoyant shaft across the surface, and if the fisherman missed he could retrieve his harpoon.