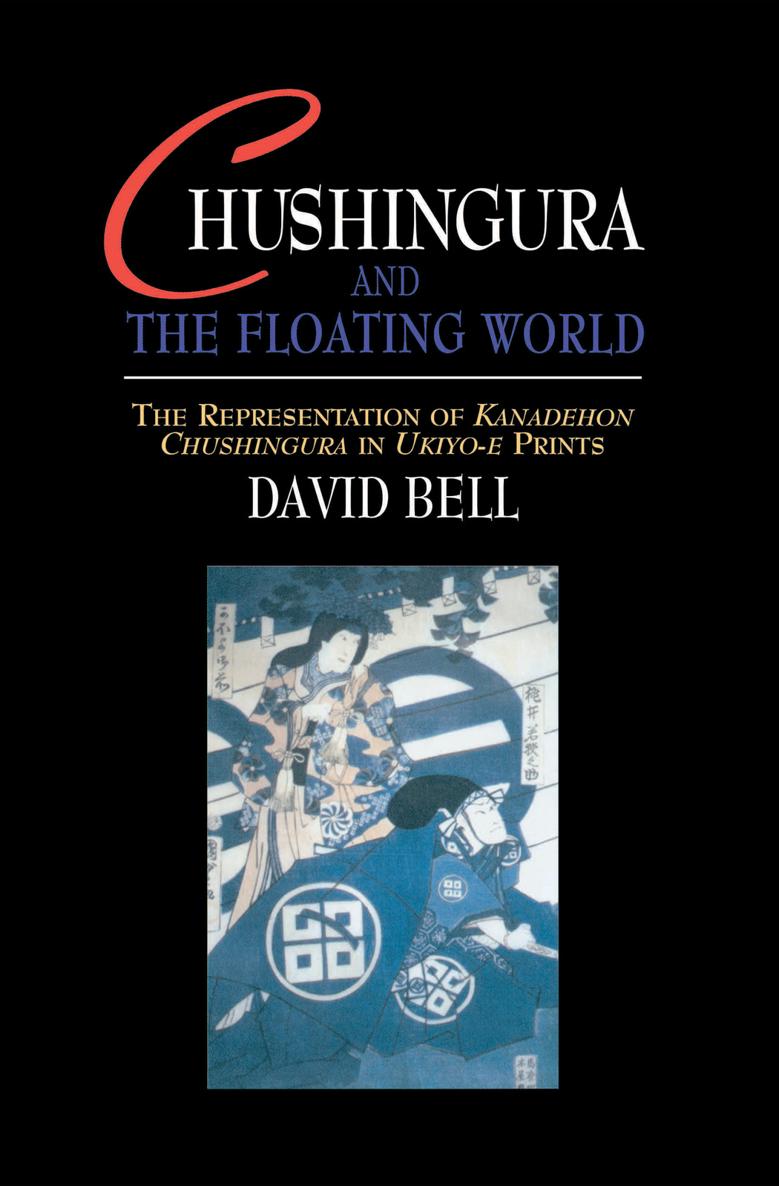

CHUSHINGURA AND THE

FLOATING WORLD

First Published 2001 by

Japan Library

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informabusiness

David Bell 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the Publishers in writing, except for the use of short extracts in criticism.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue entry for this book is

available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-903350-00-3

K anadehon Chushingura is amongst the most interesting, and is certainly one of the most popular, of plays in the kabuki repertoire. Many of the values it espouses, though founded in codes of behaviour from an earlier era, seem as relevant today as they were at the beginning of the eighteenth century. The way in which Chushingura has been represented in ukiyo-e is equally engaging. It constitutes something of a paradigm for the illustration of other kabuki themes in ukiyo-e, and as such stands as an example in which we can study the particular, virtually symbiotic, relationship between the two disciplines.

In order to establish the context in which both the play and its graphic representations developed, I have opened this study with a short account of the Ako affair, the historical event upon which Chushingura was originally founded. This is followed by a summary of the development of theatrical representations of the theme in th e jidaimono form, and an introductory explanation of the proliferation of graphic representations of the play, its themes, its characters and its actors. The popularity of the theme is explained in relation to the social world of Edo during the Tokugawa peace, to the literary genre to which it conformed, and to the reciprocal worlds of kabuki and ukiyo-e. The introductory section of the essay ends with a proposal that three areas of investigation are of interest: the first is the particular suitability of ukiyo-e formats for the illustration of Chushingura ; the second is the development of pictorial devices for the representation of kabuki; and the third is the development of a graphic form, ostensibly concerned with portraying Chushingura and other kabuki themes, but in fact centred primarily on other more independent directions of ukiyo-e , or on the sensual experience of the floating world itself.

In the second section of the essay I have examined those ukiyo-e formats which proved to be especially suitable for the representation of Chushingura, referring to works by Hokusai, artists of the Utagawa school and Shuncho. In the first instance I have described the adoption of visual equivalents for narrative structure that existed in the ukiyo-zoshi illustrated books. In the second I have examined the way such illustrations were developed as single sheet representations published in serial form. In this section also I have introduced the issue of the development of pictorial devices for the representation of Chushingura and other kabuki themes, referring specifically to graphic equivalents for theatrical constructs, particularly to the spatial conventions of the stage and the development of multi-narrative compositions.

The third section expands on the development of pictorial devices, focusing in particular on works by Toyokuni, Kunisada II, Toshinobu, Kuniyoshi, Osaka-e, Rokuzan, Gengendo I and Kunisada. Four themes have been examined here. The first is the development of theatrical and graphic devices for dramatic expression, especially through the theatrical contrivance of the mie pose. The second is the way in which ukiyo-e artists represented the dance sequences that were a fundamental component of kabuki productions. The third theme examines the development of pictorial idioms for the representation of the principal motifs of Chushingura, and particularly of its characters and their historical antecedents. The final focus is on the means employed to portray the actors of Chushingura and the development of okubi-e and nigao and conventions for identifying individuals in prints.

The following section examines the ways in which ukiyo-e artists pursued their own agendas in prints illustrating, or purporting to depict, Chushingura themes. Those agendas included alternative subject interest, as in Hiroshige's concentration on landscape and on conventions more commensurate with the description of exagerated pictorial depth than that of the shallow confines of the stage. They also included a conformity to the broader stylistic development of ukiyo-e through to the eventual decadent period of the Meiji print. Perhaps the most curious independent development in ukiyo-e was that of mitate 'parody' prints, in which the heroes, heroic ideals or melodramatic scenes of Chushingura were almost completely displaced by more fashionable contemporary subject matter, in images that now allowed a completely different insight into the 'floating world' sub-culture of late eighteenth-century Edo.

The conclusion of the essay examines the dual character apparent in ukiyo-e representations of Chushingura - the tradition of direct, faithful representation of the theme, its characters and its actors on the one hand, and the development of indirect or obliquely referential modes on the other. It offers some explanation of these two quite different characters in terms of the conditions under which ukiyo-e prints were made. Directly representational modes are explained in terms of the contractual obligations that shaped the ways in which artists worked. More oblique approaches are discussed in terms of contractual obligation, but also as a dimension of broader cultural habits and traditions. They are explained in terms of the essential differences between the mediums of kabuki and ukiyo-e and, particularly in relation to Utamaro's mitate series, as a consequence of a different point of view that gave the ukiyo-e artists a unique overview of every dimension of the floating world of Edo, and a distinct role in the construction of that world.

The essay is followed by a section of plates in which the works discussed earlier have been reproduced, in the order in which they have been introduced in the essay. The notes accompanying each plate elaborate on the particular view of Chushingura contained in each image, and offer additional explanations about the background or character of each.

The Chushingura narrative is long and complex and its cast is large. Ukiyo-e depictions often illustrate the most popular and readily recognizable scenes or characters, but in their search for increasingly novel approaches to illustrating the theme artists could also choose to portray apparently obscure or unusual scenes. For this reason I have included two appendices, one containing a list of principal characters, their roles and, where appropriate, their historical antecedents, the other offering a detailed synopsis of the kabuki and bunraku versions of the play. A glossary of the key Japanese terms used in the study follows this.