For Thomas F. Lynch, of whom its been said:

Hes a strange blend of shyness, pride and conceit,

and stubborn refusal to bow in defeat.

Hes spoiling and ready to argue and fight,

yet the smile of a child fills his soul with delight.

His eyes are the quickest to well up with tears,

Yet his strength is the strongest to banish your fears.

His hate is as fierce as his devotion is grand,

And there is no middle ground on which he will stand.

Hes wild and hes gentle, hes good and hes bad.

Hes proud and hes humble, hes happy and sad.

Hes in love with the ocean, the earth, and the skies,

Hes enamored with beauty wherever it lies.

Hes victor and victim, a star and a clod,

But mostly hes Irishin love with his God.

Contents

J ULY 1908

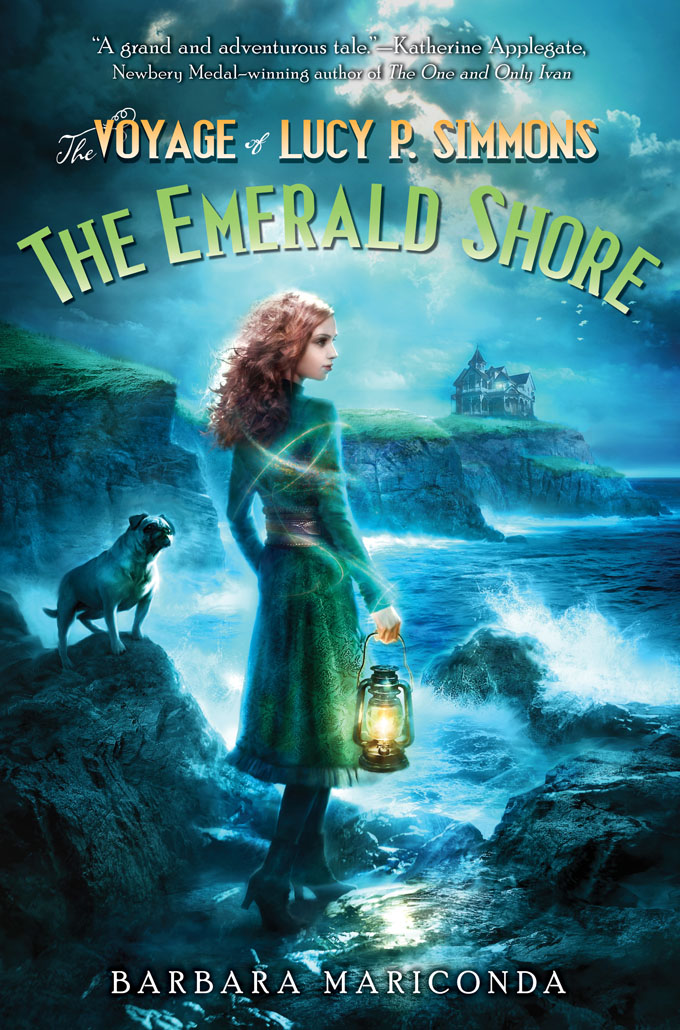

A sharp wind snapped the sails of the Lucy P. Simmons , and the chilling mist that swirled across Clew Bay dampened my face and hair. My overalls and sweater clung to my body like a cold, wet blanket. I shivered, then hugged myself tightly. Pugsley shook himself off and hunkered at my feet, stubby tail wagging despite the weather.

After a grueling ten months at sea trying to outrun the threat of the family cursefrom Port Lincoln on the southern shore of Australia, across the Indian Ocean, past the great continent of Africa, drifting for the better part of a month on flat seas with not a breath of wind, roasting beneath the equatorial sunthe promise of arriving at our destination made the weather along the Emerald Isle feel almost welcoming. I pulled Fathers spyglass from my pocket and pressed the brass-rimmed lens against my eye, searching for a scrap of green to indicate that Clare Island was in sight. I stared until my eyes began to water.

Pull this around yourself, childnot bein used t Irish weatheryoull catch a chill, ywill! Addie placed a thick shawl about my shoulders, draped her arm around me, and drew me in close. Her face was alight with excitement, despite the persistent, seamless gray gloom of sea, sky, and fog.

The ships bell began to toll and Grady appeared beside us, his weaselly face screwed in a grimace. Growin up here I knows these waters like the back of me hand... but thishe waved a thin, sinewy arm out before himthis aint no regular fog.

Walter ambled up beside me and took his place along the rail, his dark straight hair slicked to his forehead, the mist accumulating on his sweater like a fine white dew. Aw, Grady, he quipped, a smile teasing his lips, what is it this time? Weve already seen more ghosts than I care to count, a disappearing specter ship, a deck of talking cards, not to mentionhow should I put it?the unusual characteristics of this ship. I was hoping we might finish this voyage without any more irregularities.

It aint funny, Grady muttered. You kids gotta learn some rspect fer whatcha dont understand. He adjusted his cap and stared out over the starboard side. A familiar feeling of dread slowly filled me, like cold brackish water seeping into the hold. It sloshed around and caused me to shudder.

Look sharp! Captn Obediah yelled. Cant see my hand in front of my face! Tonio, sound the signal! Redsyou two watch well forward! Irish, I need you aft! Listen as well as look! The crew scrambled toward their posts, each disappearing into the thick gray mist as the warning bell soundedone ring, followed by two short clangs. This, to alert any other vessels of our presence.

I felt Annies small hand slip into my own. Shed sidled up to me, her blond hair framing her face in dank ringlets, her blue eyes enormous with alarm. Her brother Georgie appeared on my left, so much more grown up than when wed begun this queststill small for ten, but during the entire adventure hed managed to sprout considerably. Walter reassured his little sister and brother. Weve been through worse than this, he said.

But are we gonna crash? Annie whimpered. My heart did a flip inside my chest. It had been a day just like this, off the coast of Maine, when my life was first touched by the generations-old curse, as the little sloop in which Id been sailing with Mother and Father capsized, leaving me the lone survivor. Though more than two years ago, the thought of it still had the power to blind me with tears.

Of course were not going to crash!

I turned toward the confident voice of my aunt Pru. She was perched atop the poop deck, peering out beneath a visored hand, her long red hair so like mine, whipping about like the mane of a wild stallion. I took heart from her determined, regal profile, staring out into the unknown.

Hmph! Grady responded with his usual disdain. Fools! Ye ferget that rocky headlands get their names from the ships they destroy! He leaned forward, extended his skinny neck, pursed his lips, and sniffed at the air, once, twice, three times. Ye smell that? he barked.

We all inhaled, nostrils flared.

Woodsmoke, he said. Peat and ash.

Walter and I exchanged a glance. Pru turned our way, hair blowing straight back off her face. It was true. There was a peculiar burned smell, as though a fire of decaying wood had just been extinguished.

The Grey Man... , Grady whispered, his beady eyes narrowed, trying to penetrate the fog. Pugsley suddenly sprang up, the hair along his back rising in a bristly ridge. A soft growl rumbled from his throat. Even the dog sees im, Grady muttered.

Tis nothin of the kind! Addie retorted, her face full of indignation. Ye think yer the only one who knows Irish legends? She extended a protective arm around the children, glared at Grady and then at the dog. Sit, Pugsley, and stop yer bellyachin! The pup whined, circled around once, and lay back at my feet with a deflated arrumph .

The Grey Man? I asked. As if in response, a wave hit us portside, showering us with a sheet of cold water.

Grady seemed to take this as an affirmation. An Irish fairy of the worst type, he said, pausing to nibble the inside of his cheek. Sustains hisself on chimney smoke. Wherever e passes, he flings his cloak of gray mist over is shoulder, sheathing everything in is path with the pall of death. Shroudin the coastline in smoky fog, then laughin as ships are thrown into the rocks. On land, the Grey Mans presence causes potato rot, turnin em to black mush.

Annie buried her face in the folds of my overalls. Georgie puffed himself up. Quaide told me how sailors use potatoes! he shouted. In the fog, keep a bucket of taters near the bow, and heave em one at a time in the forward direction. If they splash, proceed. If not, tack!

Marni suddenly appeared, her long silver hair and pale green eyes blending with the seascape. Sailing and potato heaving have little in common, as I see it, she said lightly. And Quaide isnt here, thank the Lord. Lets all calm down. In Ireland, as I recall, the fog can roll in and out in the blink of an eye, isnt that right, Miss Addie?

Addie, just as shed done throughout the years she served as my beloved nanny, nodded with an air of reassuring confidence. Ye got that right, Miss Marni! We Irish women know when foolish sailors take t talkin blarney, we do! Thatll be all from ye, Grady! Whynt ye jest focus yer attention on sailin the ship?

Over there! Pru shouted. Off to starboard!

We all turned and gasped. To the east there was a sudden break in the clouds. A scrap of bright blue sky appeared with a huge rainbow arching down toward the greenest land Id ever seen. My heart swelled with a strange feeling of coming home, though of course Id never been there before.

Look, Annie! I gasped. Marni closed her eyes for a moment, fingering the silver locket at her throat. Walter pounded Georgie on the back and, in an instant, threw his arms around me, lifted me off my feet, and spun me in a circle.