Copyright 1997, 2012 by Gretchen Woelfle

All rights reserved

Second edition

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61374-100-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Is available from the Library of Congress.

Cover design: Joan Sommers Design

Cover images: (clockwise from upper right) The Mill at Wijk by Jacob van Ruisdael, Royal Netherlands Embassy; wind farm, iStockphoto; wind turbine, iStockphoto; North American windmill, photograph by Bob Popeck

Interior design: Sarah Olson

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Acknowledgments

A s I sat down to write this second edition of The Wind at Work, I had a new tool to usethe Internet. Its hard to fathom that when I wrote the first edition back in the mid-1990s, I did all my research in books, corresponded by US Mail, found windmill sites via long-distance telephone calls, and collected illustrations printed on paper.

However, one source of information has remained the samethe generous people who provided information, research leads, photographs, and interviews. Paul Gipe was there in 1997 to help with the first edition, and he repeated the favor for this one. Dr. T. Lindsay Baker, still publishing the Windmillers Gazette, also helped. Dan Juhl of Juhl Wind, Inc.; Richard Miller of Hull, Massachusetts, Municipal Light Plant; Michael Wheeler of enXco; and Peggy McCoy of the Cascade Community Wind Project shared their time and experience. Kit Gray was a master of all things photographic. Alice Woelfle-Erskine proved an invaluable research assistant, and Cleo Woelfle-Erskine, writer and scientist, gave the book an astute reading as he himself works to heal the planet. Finally, Cynthia Sherry and her staff at Chicago Review Press deserve a big shout-out for keeping the first edition of The Wind at Work in print for 15 years and for overseeing its latest version. My thanks to them all.

1

Harnessing Wind Power Through Time

N ight fell on the flatlands of Holland. The wind howled, rain slashed to earth, and waves broke higher and higher on the beach. Flashes of lightning revealed a high wall of earth built to hold back the sea. Waves crashed against this dike, throwing water to the fields beyond and washing away parts of the dike itself.

The Dutch called the sea the Waterwolf, and tonight the Waterwolf was on the prowl, trying to steal their lands. All night long flickering lanterns moved along the top of the dike as villagers kept watch. If the dikes broke, the Waterwolf would swallow their farms and homes.

By morning, the rain subsided and the wind dropped. The storm was over. The dikes had held. Tired Dutchmen stumbled home to bed.

But there was no rest for the windmillers. All night they had worked the windmills to pump water from the overflowing canals back out to sea. Now they had to drain the flooded fields to save the crops. For days and nights, giant windmill sails would turn, pumping and pumping until the fields were dry. The wind that nearly destroyed the land would now help to save it.

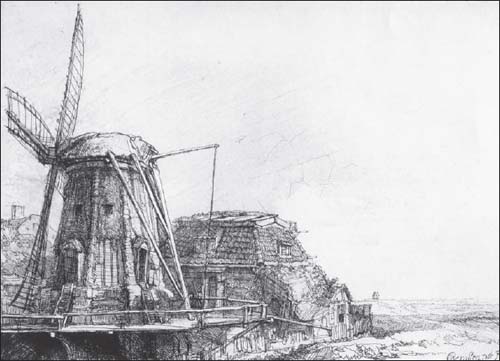

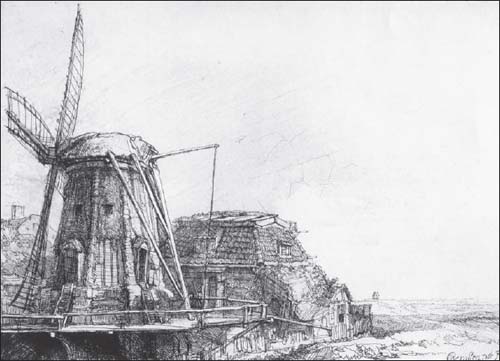

Rembrandt van Rijn (1609-1669), one of the Netherlands greatest artists, was the son of a windmiller. He grew up across the street from his fathers malt mill in Leyden. The mill stood on the banks of the Rhine River (spelled Rijn in Dutch). The family took this name for their own. Here Rembrandt portrays a smock mill and the millers house next door. Rijksmuseurn-Stichting, Amsterdam

The History of Wind Power

Wind is created by the sun as it warms the earth unevenly. Warm air expands and rises. Cool air rushes in to take its place. This air movement is what we call the wind.

For more than a thousand years people have harnessed the wind with windmills. People used the wind to propel sailboats on the water long before they built windmills on land. Billowing sails filling with wind replaced the hard work of men rowing and paddling. Eventually, wind-powered machines moved on land and saved a lot of heavy labor. The wind-filled windmill sails then turned a shaft, wheels, gears, and finally, millstones, water pumps, or other machines. Before the invention of windmills and water mills, men or animals turned heavy millstones by trudging around and around in a circle, hour after hour, day after day, crushing grain to make flour. It was mind-numbing, body-breaking work.

The wind is not a perfect source of energy. It can be steady or gusty. It can change direction in a few seconds. It can grow to the force of a hurricane or die completely. Scientists can predict daily and seasonal wind patterns, but these patterns wont tell if or how much the wind will blow tomorrow afternoon. Even so, the wind has been reliable enough for many uses through the centuries.

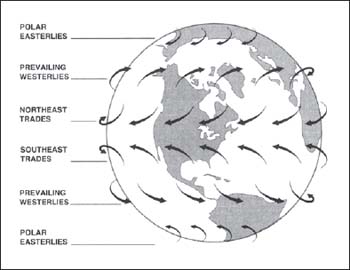

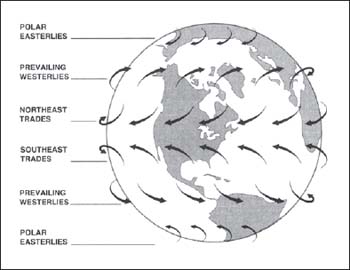

Wind is created by the sun as it warms the earth unevenly. Lands near the equator get more sun than those near the poles. Summer brings more sun than winter. Warm air expands and rises, and cool air rushes in to take its place. The drawing shows the usual, or prevailing, winds in different parts of the earth. Kristin Brivchik

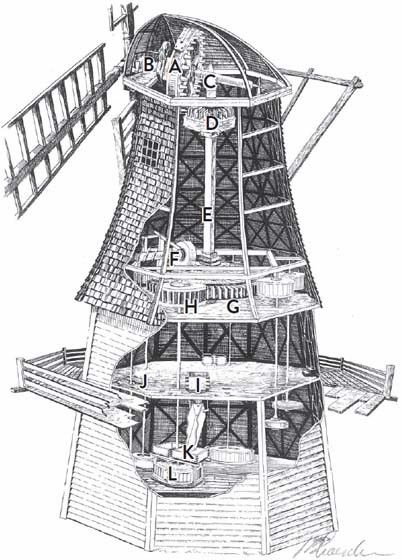

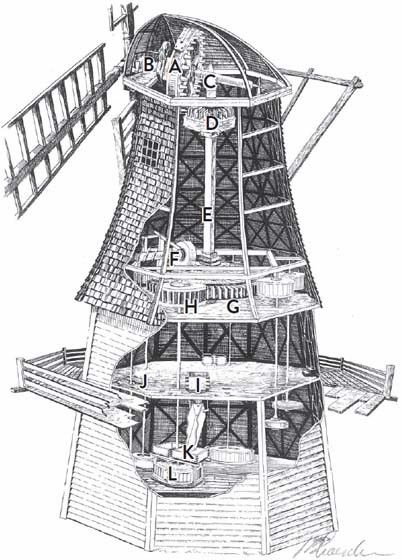

This cutaway drawing of a windmill shows different parts of the machinery in a grist (grinding) mill.

Bruce Loeschen

A. Brake wheel: Cogwheel mounted on the windshaft that drives the wallower, and around the rim of which the brake contracts to stop the mill.

B. Brake mechanism: Mechanism to stop the sails from turning.

C. Windshaft: The axle on which the sails are mounted.

D. Wallower: The large circle with cogs that turns the main shaft.

E. Main shaft: The main upright driving shaft.

Next page