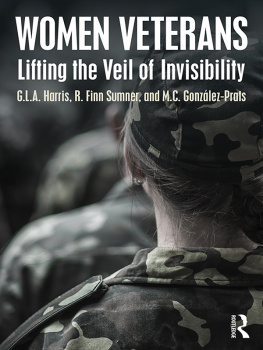

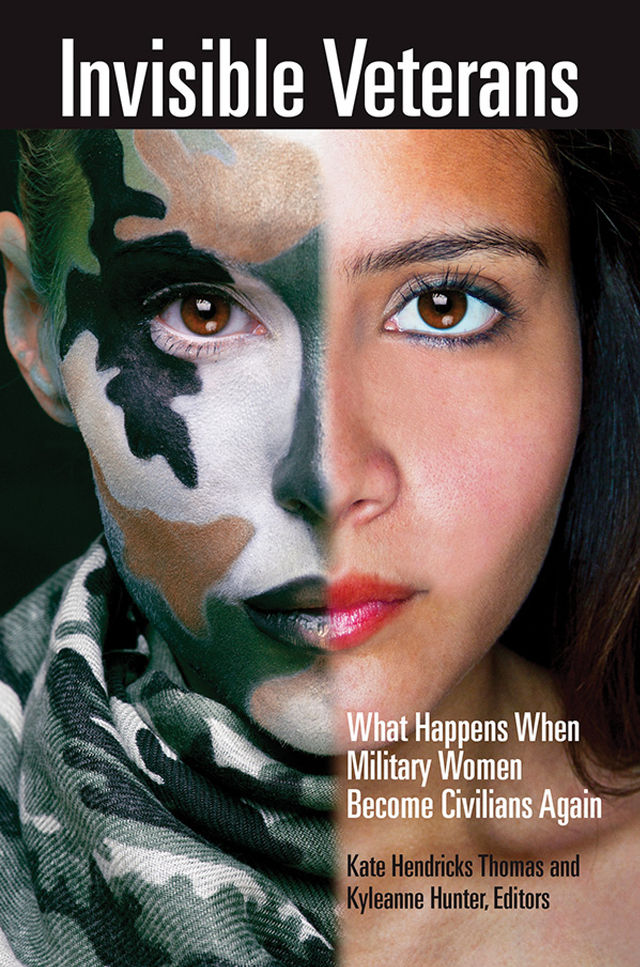

Invisible Veterans

Invisible Veterans

What Happens When Military Women Become Civilians Again

Kate Hendricks Thomas and Kyleanne Hunter, Editors

Foreword by Carrie Ann Alford

Copyright 2019 by Kate Hendricks Thomas and Kyleanne Hunter

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thomas, Kate Hendricks, editor. | Hunter, Kyleanne, editor. | Alford, Carrie Ann, writer of foreword.

Title: Invisible veterans: what happens when military women become civilians again / Kate Hendricks Thomas and Kyleanne Hunter, editors; foreword by Carrie Ann Alford.

Other titles: What happens when military women become civilians again

Description: Santa Barbara, California: Praeger, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019021182 (print) | LCCN 2019021766 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440866432 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440866425 (print: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Women veteransUnited StatesSocial conditions 21st century. | Women veteransUnited StatesBiography. | United StatesArmed ForcesWomenSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC UB357 (ebook) | LCC UB357 .I585 2019 (print) | DDC 305.48/470973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019021182

ISBN: 978-1-4408-6642-5 (print)

978-1-4408-6643-2 (ebook)

23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available as an eBook.

Praeger

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

147 Castilian Drive

Santa Barbara, California 93117

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

For my mother. Your hard work and constant support have never been invisible.

Kate Hendricks Thomas

To my sisters in arms and all who have supported us.

Kyleanne Hunter

Contents

Kate Hendricks Thomas and Kyleanne Hunter

Carrie Ann Alford

Andrea N. Goldstein

Teresa Fazio

Kayla M. Williams

Nancy A. Glowacki

Erika Cashin

Kate Hendricks Thomas, Ellen Haring, Justin T. McDaniel, Kari L. Fletcher, David L. Albright, and Elizabeth Brandley

Antonieta Rico

Kari L. Fletcher and Cathleen A. Lewandowski

RLynn Johnson

Heliana Ramirez and Katharine Bloeser

Mariana Grohowski and Patricia Y. Jones

Scott Jensen

Sarah Plummer Taylor

Rebecca H. Best

Lydia Davey

David Smith

Mary Beth Bruggeman and Gina Rosen

Kate Hendricks Thomas and Kyleanne Hunter

We are Marines. No longer in uniform, today we are both academic researchers. We were also both almost statisticsnumbers on a page that people use to evoke emotions devoid of context. That is the reason we dedicate our personal and professional lives to advocate for women veterans and to conduct research in the field of women veterans wellness. We struggled to leave the active-duty military and become civilian versions of ourselves again. Despite appearing successful, or even normal on the outside, there was always an almost nagging preoccupation with not belonging. We see ourselves in some of the findings cited throughout this volume.

For two women veterans who work with data for a living, the realization of how challenging transition is for servicewomen like us and our peer group is sobering.

It is well documented that veterans, especially women veterans, suffer from a lack of belonging and of connection. During active duty, this manifests as a question of whether you feel like you can tell someone that youre experiencing trauma at home or simply need to power througha question of whether you can tell someone that youre struggling with self-medicating or actively hide it because you learned your lesson well that for Marines, pain is weakness. As women transition into the civilian world, these questions remain. If you ask us, too many of us feel that care systems (both nonprofit and government) were often just not built for women, and more of us also report that we leave the military with less of one very important protective factorsocial support.

Women veterans are 250 percent more likely than civilian women to commit suicide, and women who do not use VA services have seen a 98 percent increase in rates. To us, the suicide numbers are more than just statistics. Behind all of these numbers are stories of keeping a strong, silent public face even when we are struggling personally. From an academic standpoint, we recognize that some of the issues that are driving women to suicide are a result of a lack of cohesion and inclusion due to institutional barriers. These issues become compounded after indoctrination into a culture that teaches us never to show weaknessneither emotion nor tears are viewed kindly in the active-duty component. From a personal standpoint, these findings are even more poignant.

With the benefit of a little age and a lot of hindsight, we look back at our time on active duty and our transition from it as a time of tremendous risk and isolation. We are fortunate that throughout the pain and loneliness, we were in a position to seek help and counsel and be here today to bring invisible veterans to life. In our new lives as social science researchers, we work with data that indicate association between reported support deficits for military women and invisibility. Often it is easy to focus just on the data. However, sometimes, the data are personal and remind us why we do the work that we do.

The very word veteran calls to mind the image of a man, especially combat veteran, for most people. But there are over 1.6 million women veterans in the United States. Of these, 30 percent are from post-9/11 era, meaning that they are younger and still have a life ahead of them to engage with their communities. Many of us served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Indeed, post-9/11 women veterans stand a bit apart from a normal crowd.

Both the total number and relative percentage of Americans serving in the military are on the decline, and thus, the veteran population (both male and female) has also been declining for decades. What this means for our community of peers today is that only about 1 percent of the total American population is veteran, and a small slice of that percentage served during the past 18 years that we have been at war. Women are an even smaller percentage and rarely benefit from the traditional trappings of the hero returned home. One only needs to do the math to see how easy it is to wind up drinking alone for a military woman, often with a deployment or two under her belt.

Women veterans share many of the exact same concerns of our male colleagues, yet also face unique issues, especially when it comes to accessing services after we leave active duty. We think of ourselves as both resilient and lucky. Kyleanne left an abusive relationship to become an advocate for women and to pursue a doctorate in security studies, focusing on the role that women play in military effectiveness. Kates work today focuses on undiagnosed mental health conditions, because if we can help veterans when they are struggling all alone, we can change those suicide numbers. Yet, we are only here because we have been through what it means to be alone and near the brink. We are dedicated to being not only advocates or scholars but both. This work represents the personal and the professional.