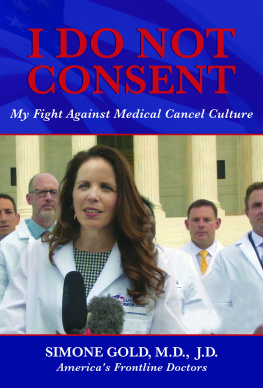

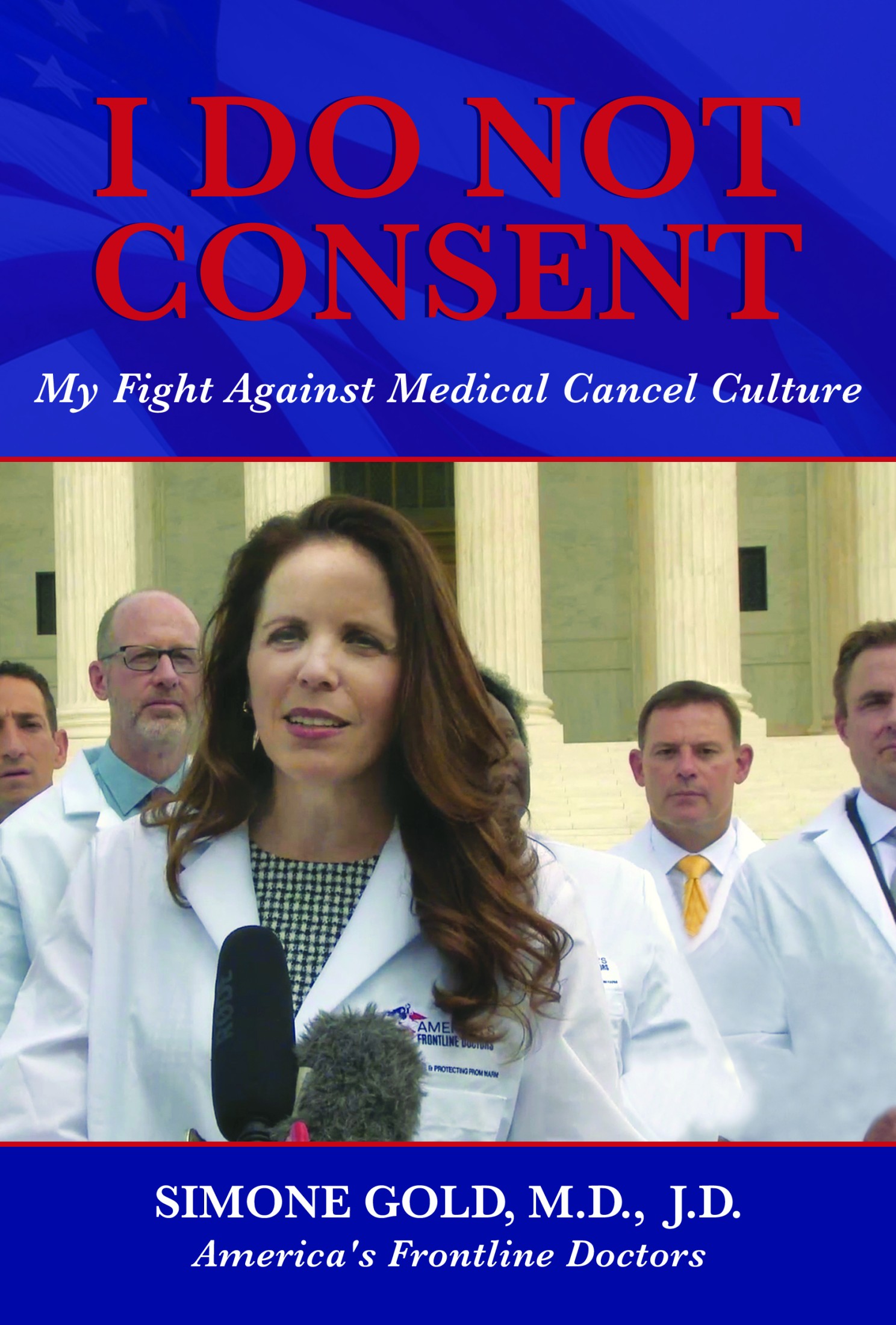

2020 by Simone Gold, M.D., J.D.

This book contains advice and information relating to health care. It should be used to supplement rather than replace the advice of your doctor or another trained health professional. You are advised to consult your health professional with regard to matters related to your health, and in particular regarding matters that may require diagnosis or medical attention. All efforts have been made to assure the accuracy of the information in this book as of the date of publication. The publisher and the author disclaim liability for any medical outcomes that may occur as a result of applying the methods suggested in this book.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the author and publisher.

T he virus arrived largely without warning, particularly for the general public. As events unfolded, media coverage portrayed a world at war with an invisible combatant. Glowing red blobs superimposed on the map showed the blast radius of infections rippling out from its epicenter in Wuhana city in eastern Chinas Hubei Province and home to Chinas only level four biosafety labthen to the industrial north of Italy, on to the rest of Europe, and eventually to population centers on the coasts of the continental United States. We were watching unfold a situation that no one alive had seen or managed. Sure, we read about global viral pandemics in history books and medical journals. But being on the frontlines and dealing with it in real time was a new experience.

COVID-19 is the respiratory disease caused by the new or novel human coronavirus. We knew at the time that the pathogen spread through droplets in coughs and sneezes, and that it was highly contagious. Precautions were taken. These included hand-washing, disinfection, and social distancing. Handshakes were out; people avoided large group gatherings when possible. Most important of all, Americans from the boardroom to the corner bodega were told to stay home from work if they felt sick.

My state of California recorded its first case of the virus on January 26, 2020. By February the international body responsible for naming viruses had settled on SARS-SoV-2 owing to its genetic similarities with the class of virus responsible for the Chinese SARS outbreak of 2002. President Trump declared a public health emergency on February 3. Complex geopolitics combined with a naive trust in Chinese health officials led the World Health Organization (WHO) to delay its labeling COVID-19 a global pandemic until almost the middle of March.

In the United States, the disease began as a cluster of infections in a suburban nursing home east of Seattle and resulted in the first U.S. death associated with COVID-19 on February 29. The same day, the U.S. surgeon general admonished Americans for buying face masks, tweeting Seriously peoplestop buying masks! They are not effective in preventing general public [sic] from catching #Coronavirus . As new cases and deaths climbed in March, fears of overwhelmed, under-equipped hospitals grew as well.

By mid-March President Trumps administration had issued new guidelines to slow the viruss spread, including avoiding discretionary travel and groups of ten or more people when possible. The medias coverage of the lack of testing supplies intensified. According to a poll released by the American Psychiatric Association, 48 percent of Americans reported that they felt anxious about the possibility of contracting coronavirus. Meanwhile, healthcare workers on the frontlines bore the brunt of the emergencyand the risk.

Then on March 13, President Trump declared a national emergency, directing billions of dollars and a massive intergovernmental effort to contain the spread. Like a majority of Americans in those days, doctors were still unclear what was happening. To the extent the US media commented on COVID-19, its coverage had been uneven and slow to catch up with partisan domestic priorities such as the impeachment and the Mueller report. Elected officials in both parties sent mixed signals based on bad information from the WHO, China, and other sources.

Not long afterwards I started seeing my first COVID patients. The question in my mind was how to provide the most effective care given the uncertainty of the moment. My colleagues were placing virtually every symptomatic person they saw on oxygen and treating most with antibiotics. These patients had their heartbeats monitored as well.

The common antimalarial drug called hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) had been shown to be effective against the first SARS outbreak close to two decades ago. Could it work now, I wondered? I knew about HCQ because many years ago when I was planning a trip to Africa, the travel physician just handed me the prescriptionno conversationjust, Here, take this, start now. It was a simple, white tablet, taken weekly. The drug can be safely taken by pregnant women and nursing mothers, the young and the old.

My personal experience with the drug coupled with my physicians knowledge that its extremely safe meant I was excited about its treatment possibilities for COVID-19. The U.K.s Imperial College COVID Response Team had recently predicted more than two million Americans could die if no actions were taken. HCQ was something I could use to treat patients right away in an emerging situation.

My first confirmed positive patient was a woman in her fifties in the mid-stages of COVID-19. When I saw her in the emergency department of the hospital where I worked, her symptoms included a low fever and some shortness of breath with chest pain, but otherwise she was stable. The woman was somewhat sick and faced a significant chance of becoming critically ill, but at the moment she was in pretty good shape. She could take medications on her own, had a family prepared to monitor her progress, and could return if her condition worsened. She was the perfect outpatient candidate for hydroxychloroquine. Lets call her Patient One.

In the early days of the pandemic, people were innovating and trying new things. For example, by late March the FDA was letting doctors apply to administer convalescent plasmathe antibody-rich blood drawn from COVID-recovered individualsto their patients on a case-by-case basis. They pointed out that plasma had been an effective treatment for other coronaviruses. I saw HCQ in much the same way. Early-adopter physicians like me were intrigued by the potential of HCQ. The opposing opinion was simply do what you think is best. At this point there was no controversy.