Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Michael Morgan

All rights reserved

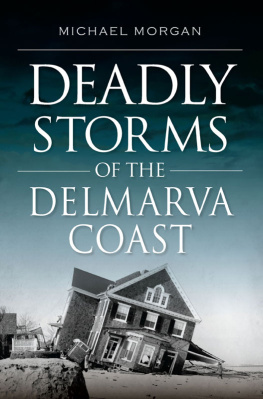

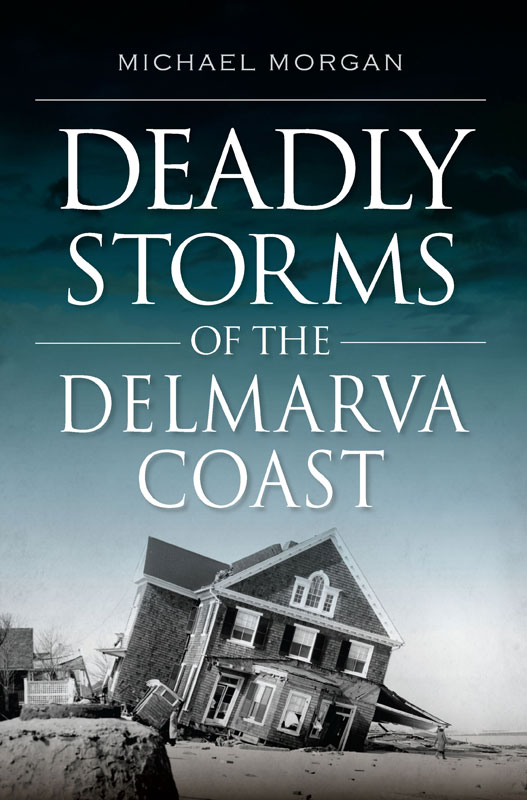

Front cover: The Grier house in Rehoboth. Courtesy of the Delaware Public Archives.

First published 2019

E-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.677.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019932626

print edition ISBN 978.1.62585.938.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

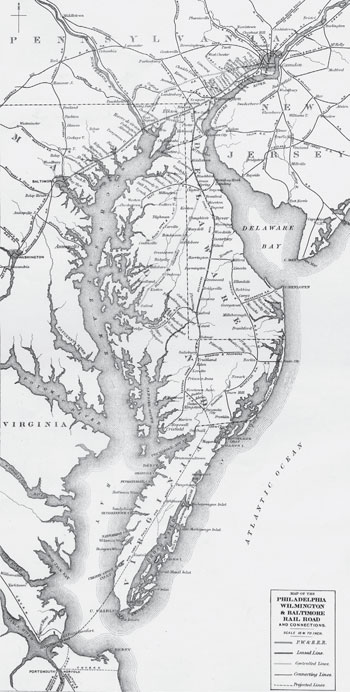

Outlying along the Atlantic coast reaching from Cape Charles to Cape Henlopen, from the Chesapeake to the Delaware Bay, the artist Howard Pyle wrote in 1879, is a continuous chain of islands, corresponding to the Sea Islands of the Carolinas, separated from the mainland by a sheet of water varying in width from a quarter of a mile to seven or eight miles, bearing different names in its more considerable portions, such as Chincoteague Sound, the Broadwater, Sinepuxent Bay, and so forth. These islands, varying in length from less than a mile to two or three leagues, are of two characters, either low and marshy, covered with a thick growth of rank sedge, the refuge of countless millions of fiddler crabs, the brooding place of numberless gulls, marsh hens (Virginia rail), and willits (a variety of snipe), or sandy, and covered with alternate strips of pine glade and salt meadows, on some of which run wild a peculiar breed of ponies, called beach hosses by the natives.

When Pyle wrote his description of the Delmarva coast, the seaside resorts of Rehoboth, Delaware, and Ocean City, Maryland, were barely a half-dozen years old, and the barrier islands were mostly undisturbed by human activity. For eons, the wind and waves had quietly rearranged the Delmarva beaches. In some areas, the littoral currents pushed the sand southward; in other areas, the sand moved northward. In the winter, the prevailing winds robbed the beaches of precious sand, but during the summer, they put it back. There were also larger forces at work. Delmarva sits on one of the earths tectonic plates that is slowly sinking into the Atlantic Oceanperhaps as much as a foot per century. In addition, the seas, fed by the melting glaciers and ice caps, are rising as much, if not more. The change in sea level and the prevailing winds have driven the Delmarva coast westward, but this movement occurs so incrementally that it has been largely ignored. What have been noticed are the changes wrought by storms, and these are the subjects of this book, which concentrates on the Delmarva coast from the southern tip of Assateague Island to the northern end at Cape Henlopen.

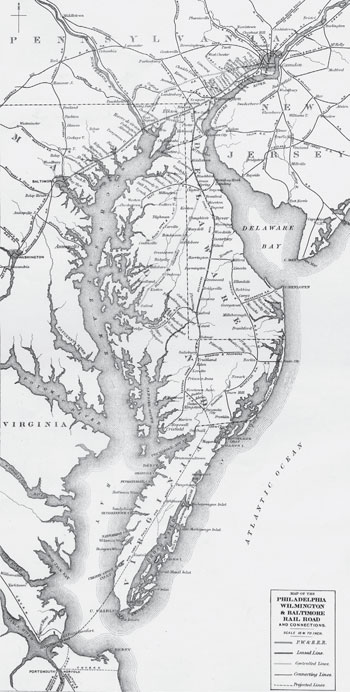

This nineteenth-century map shows the Delmarva barrier islands that shielded the peninsula from the Atlantic Ocean. Courtesy of the Delaware Public Archives.

It would not have been possible to write this book without the assistance of the dedicated people who staff libraries, archives and historical societies. I would like to thank Michael DiPaolo of the Lewes Historical Society and the staffs of the Assateague Island National Seashore, the Snow Hill Public Library and the Julia A. Purnell Museum for their assistance in securing material on the storms that have affected the Delmarva coast. I would also like to thank Randy L. Goss of the Delaware Public Archives for his assistance in securing many of the images that appear in this book. In particular, I would also like to thank Nancy Alexander, of the Rehoboth Historical Society, who suggested this topic, for her patience while I combed through the societys collection of print material and photographs.

I would also like to thank my son Tom and his wife, Karla, for their support and technical assistance. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Madelyn, for her constant editorial advice and support. She read every word in this book numerous times and spent countless hours correcting my spelling, punctuation and grammar. Without her help and support, this book would not have been possible.

CHAPTER 1

ASSATEAGUE: 1524

MASTERS OF THE WIND

We reached a new country, Giovanni da Verrazano wrote in 1524, when the Italian explorer first saw the barrier islands of North America along the Carolina coast, which had never been seen by any one, either in ancient or modern times. At first it appeared to be very low, but on approaching it to within a quarter of a league from the shore we perceivedthat it was inhabited. The son of a Florentine silk merchant, Verrazano was not impressed with the low, sandy islands that lined the coast, and he sailed farther southward to look for an inlet that would lead to deep quiet water to harbor his ship, the La Dauphine. Seeing no appropriate inlet leading to the coastal bay, he turned northward toward the Delmarva coast.

Italian sea captains sharpened their navigation skills by carrying religious Crusaders and merchandise on the Mediterranean Sea; in the late fifteenth century, they ventured into the Atlantic. There, they mastered the art of ocean sailing equipped with a few simple toolsan all-important compass to show direction, a line and chunk of wood dropped over the side to estimate speed, a traverse board to record the course and a simple knowledge of the geometry of the earth and the North Star to determine latitude by simple celestial navigation. Above all, however, experienced navigators relied on their knowledge of the winds: prevailing easterly winds to carry a ship to America, prevailing westerly winds to bring mariners home to Europe, signs of coming storms, strong winds, light winds, winds that would carry a ship to sea and winds to bring it back again. The success of their voyages and their lives were determined by their mastery of the winds.

Educated in France, Verrazano made several sea voyages and became a competent navigator. In 1524, he secured a commission from the king of France to find open water that would lead to the Pacific Ocean and the lucrative markets of the Far East. Instead, he found the barrier islands. Common to the east coast of North America, these low-lying sandy islands were separated from the mainland by a coastal bay and ran parallel to the coast. Verrazano may have encountered European barrier islands that lined the eastern edge of the North Sea from the Netherlands to Denmark, but the spotty islands on the eastern side of the Atlantic Ocean paled in comparison to the sandy barriers that lined the North American coast. When he reached the Outer Banks of North Carolina, the explorer remained so far away from the coast that he mistook the broad expanse of Pamlico Sound for the Pacific Ocean. Continuing northward, Verrazano arrived at the southern tip of the Delmarva Peninsula, where he encountered the line of barrier islands that stretch from Cape Charles to Cape Henlopen. In much of Virginia, the barrier islands are mostly a disconnected series of islands set a considerable distance from the mainland; to this day, they remain undeveloped and sparsely populated. Beginning at the southern tip of Assateague, however, the islands are a broad ribbon of sand divided by a number of inlets and separated from the mainland by narrow coastal bays. Buffeted about by winds and waves, these islands sands are constantly changing. Inlets appear and disappear, and chunks of the beach become islands only to be reattached to the mainland decades later. Five centuries ago, Verrazano decided to venture into one of the coastal bays. Historians debate the exact locations that Verrazano visited on this voyage, but it appears that he entered Chincoteague Bay from the south and sailed northward until he anchored in the vicinity of Sinepuxent Inlet. Anchoring

Next page