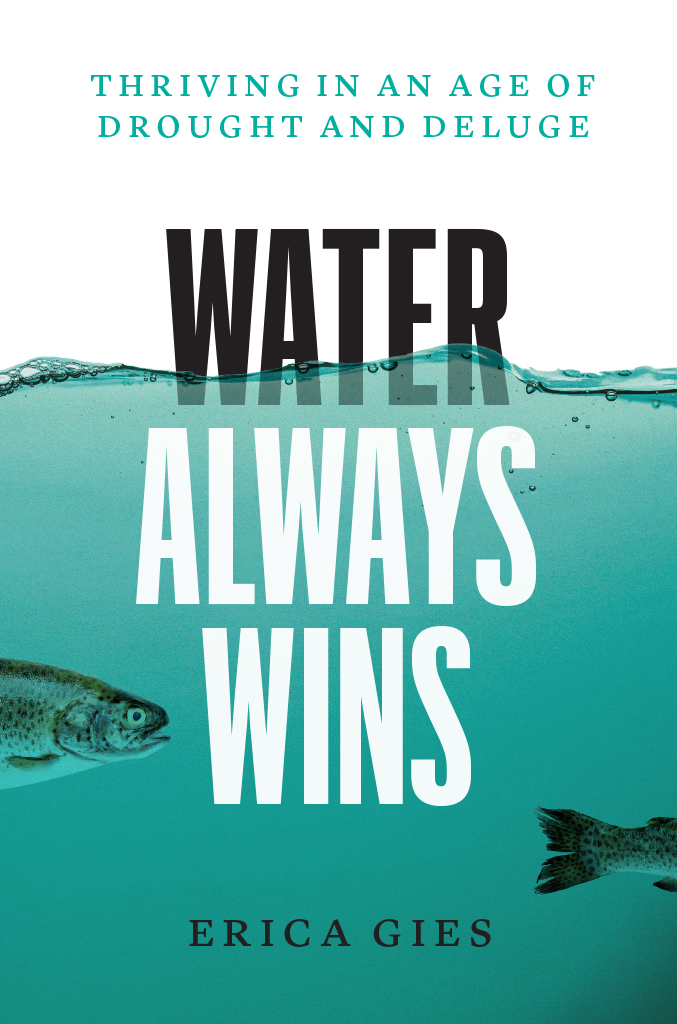

Water Always Wins

Water Always Wins

Thriving in an Age of Drought and Deluge

Erica Gies

The University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

2022 by Erica Gies

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71960-3 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-71974-0 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226719740.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gies, Erica, author.

Title: Water always wins : thriving in an age of drought and deluge / Erica Gies.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021050909 | ISBN 9780226719603 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226719740 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Water conservation. | Water resources development. | Freshwater ecology.

Classification: LCC TD388 .G54 2022 | DDC 333.91/16dc23/eng/20211116

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021050909

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For water and all its relations, be they mineral or microbial, beaver or bipedal.

And for the water detectivesfor their curiosity, vision, and work toward a livable future.

Contents

How Ancient Rivers Can Help Ease Droughts

Waters Relationship with Tiny Forms of Life

The Original Water Engineers

How Water Shaped Culture in Ancient Peru

Antidote to the Industrial Era

Protecting Water Towers in Kenya

Where Fresh Water Meets Salt

Living with Water

On a sunny winter day in San Francisco, Joel Pomerantz brakes his bike in Alamo Square Park near that famous spot where Victorian houses, the Painted Ladies, front the citys modern skyline.

Do you notice anything? he asks me.

I brake too and look around, flummoxed. I lived in this city for seventeen years and have been to this park countless times. Everything seems ordinary. On the paved path at our feet, Pomerantz points to an oblong puddle, which I would assume was left over from the last sprinkler watering.

That?! I ask, incredulous.

Look closer, he says, pointing to its ring of mossy scum. Thats a sign that this water is nearly always here. This diminutive puddle, which I have likely passed without noticing many times, is actually evidence of natural springs beneath the park that seep continually, he tells me. Its a small sign of waters hidden life, the actions this life-sustaining compound continues to pursue, despite our illusion that we control it. As climate change amplifies floods and droughts, people like Pomerantz are recognizing the importance of such minutiae that highlight waters agency.

In his free time, Pomerantz hunts and maps ghost streams, the creeks and rivers that once snaked across the San Francisco Peninsula before humans filled them with dirt and trash or holstered them into pipes, then erected roads and buildings atop them. Such treatment of waterways has become standard practices in cities, where more than half of us live worldwide. Pomerantz has devoted three decades to exploring the city with water on his mind, making him a kind of water detective. His eyes see what others misslike this puddle, or certain water-loving plants that are clues to lost creeks. He gestures toward the trees that line the parks edge on Fulton Street. Willows are like a flag, he says. In fact, the name of this park is actually a plant clue: lamo means poplar in Spanish, a species related to willows and other streamside trees .

A few blocks away, he checks for traffic, then guides me to a manhole in the middle of residential Eddy Street near busy Divisadero. Cocking our heads, we hear the sound of rushing water. When that sound is constant, he says, especially in the middle of the night, its a creek imprisoned in a sewer pipe, not somebody flushing.

Later, Pomerantz and I bike to Duboce Triangle, another small park, this one between the Lower Haight and Castro Districts. Duboce lies at a low point of The Wiggle, San Franciscos beloved bike path. Although unmarked for many years, bikers long followed this route , weaving through valleys at the base of hills. A stream, now buried, was the original traveler of The Wiggle, and along its path through Duboce Triangle the city has now built bioswales, vegetated ditches to hold runoff from heavy rains. Although Ive biked the route myself frequently, I never knew it was pioneered by a stream. It makes sense, when you think about it. Cyclists, like water, look for the path of least resistance.

Pomerantzwho has published a map of San Franciscos lost waterways on his Seep City website, advised local agencies as a consultant, and leads walking tours to share his hard-won knowledgeis not alone in his obsession. In Brooklyn, urban planner Eymund Die-gel has mapped Gowanus Creeks lost watershed. In Victoria, British Columbia, artist, poet, and environmental activist Dorothy Field worked with local historians and First Nations to track the hidden path of Rock Bay Creek, then installed signs and street medians inlaid with salmon mosaics to draw attention to where it still flows underground. As curiosity about buried waterways grows in the popular imagination, the quirky passion is now a global phenomenon. Subterranean explorers, featured in a 2012 film called Lost Rivers, are discovering buried waterways encased in pipes below Toronto, Montreal, and Brescia, Italy. The Museum of London had a Secret Rivers exhibition in 2019 to reacquaint Londoners with their lost streams.

Secret rivers, ghost streams, hidden creeks: learning of their existence arouses our innate attraction to mystery and our passion about the places we live. What we learn about the past triggers amazement because our quotidian landscape is so transformed. Weve dramatically altered waterways outside of cities too. Weve straightened rivers meanders for shipping, uncurled creeks to speed water away, drained and filled wetlands and lakes, and blocked off floodplains to create more farmland or real estate for buildings.

But our curiosity about waters true nature is not idle, nor an indulgent wish to return to the past. Water seems malleable, cooperative, willing to flow where we direct it. But as our development expands and as the climate changes, water is increasingly swamping cities or dropping to unreachable depths below farms, generally making lifeours and other speciesprecarious. Signs of waters persistence abound if we train ourselves to notice them. Supposedly vanquished waterways pop up stubbornly, in inconvenient ways. In Toronto, tilted houses on Shaw Street near the Christie Pits neighborhood were long a local novelty, but most people didnt know that the ghost of Garrison Creek was pulling them out of plumb. Worldwide, seasonal creeks emerging in basements are evidence that those houses encroach on buried streams. In my partners moms neighborhood in suburban Boston, most houses come with sump pumps because the development was built on the local Great Swamp. And in the wreckage of disasters like Superstorm Sandy or Hurricane Harvey, we see that homes built atop wetlands are the first to flood.

Next page

![David E Newton] - The global water crisis : a reference handbook](/uploads/posts/book/104432/thumbs/david-e-newton-the-global-water-crisis-a.jpg)

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).