10. Flight Nursing on the Pacific Front:

Alaska, China-Burma-India

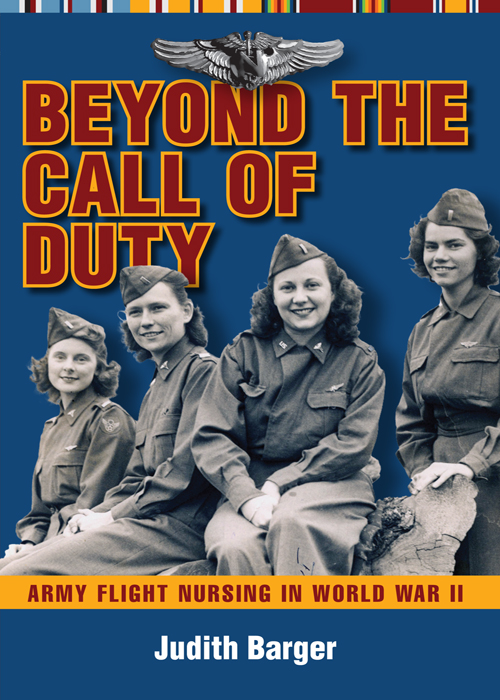

A t the height of World War II, five hundred army flight nurses served with the army air forces as members of thirty-one medical air evacuation squadrons located throughout the world.

Faced with casualty rates growing from about five thousand a month in 1943 to eighty-one thousand a month by the end of 1944, military leaders were quick to realize the value of flight nurses and enlisted technicians in making the newly organized air evacuation program a success. We found afterwards that the use of nurses was probably the wisest thing the air evacuation [program] ever had, remarked Colonel Ehrling Bergquist after the war. Bergquist, who had been command surgeon for the 9th Troop Carrier Command and later the 1st Troop Carrier Command in Europe during the war, continued: The young ladies were highly enthusiastic, and they sold the air evacuation program. They wore distinctive uniforms, and people knew who they were. The result was that whenever people wanted to talk about air evacuation These specially trained army nurses had met the challenge and taken nursing to new heights. Often decorated for their accomplishments, they exemplify the ability of a group of nurses to cope successfully with the challenges of war.

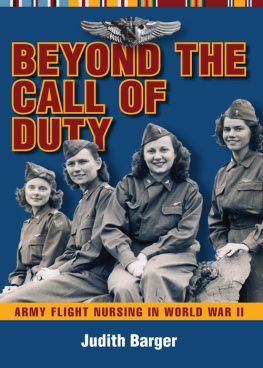

The venerable history of the United States Army Nurse Corps, of which these women were a part, has been told elsewhere. This book chronicles the story of army flight nursing in World War II from the years preceding the war when pilot Lauretta Schimmoler founded the civilian Aerial Nurse Corps of America with intent to provide flight nurses for a military program, to the establishment of the air evacuation program in the United States Army Air Forces and the training of the army nurses who provided in-flight patient care, to the participation of flight nurses in air evacuation missions overseas.

A unique feature of the book is the inclusion of firsthand accounts by twenty-five of these remarkable women, whom I was privileged to interview in 1986 when their recall for events of their flight nurse duty was still remarkably vivid and informative. I was on active duty as an air force nurse at the time, living in San Antonio, Texas, where military colleagues helped me locate a handful of former army flight nurses in the city and one out of state. I met some of them at luncheons for retired military nurses in the city. These women gave me names and contact information for others who had been in their squadrons during the war. I contacted them by telephone, and in some cases by letter as well, to seek their participation in a study about coping with war. Those who declined cited their own or their spouses health, a busy schedule, travel distance and expense for me, and the feeling that their experiences would not prove helpful. I conducted all interviews in person with those who agreed to take part, traveling at my own expense to a location of their choice. Most interviews were in the womens homes, though several took place at a hotel in Cocoa Beach, Florida, where I was asked to speak at a World War II Flight Nurses Association reunion. I had served as a flight nurse myself, assigned to the 9th Aeromedical Evacuation Group at Clark Air Base in the Philippines from 1973 to 1975, logging over 1,260 flight hours on air evacuation missions with patients throughout the Pacific.

The stories the women shared with me often confirmed and occasionally contradicted the literature about army flight nursing in World War II found in unit and medical histories, air evacuation histories, human-interest stories written during and shortly after the war, and oral histories recorded years later. But always the interviewees accounts are insightful, offering a glimpse of what it was really like to serve as a flight nurse in World War II and to cope with the exigencies of wartime nursing. Their stories are both humorous (It is possible for a nurse with slacks on to aim at the pilots relief tube, but, believe me, its very difficult, and you have to hope that the plane is going to fly steady while youre there!) and heartfelt (But you feel so helpless when your patients going out and there isnt anything you can do. We had no oxygen on board, no IVs to give himnothing to help a patient like that. And all I could do was just watch him.), entertaining (One time one of the planes I got was just covered with glossy prints, and they were all nudes. So I took my Band-Aids, and I dressed the entire ceiling of the plane.) and revealing (I was petrified of flying. I was scared to death to fly. I was scared on every trip.).

By the time I completed this book, only five of the twenty-five flight nurses whom I had interviewed were known to be living. I tried repeatedly to obtain their consent to include material from their interviews with me, but not all responded. As other authors have found when recounting the stories of World War II veterans, over the intervening years some of the interviewees had been lost to declining health, changes in living arrangements, and unknown exigencies that come with the passage of time.

I am grateful to staffs of the following agencies for permitting me access to documents and photographs held in their archives between 1974 and 1986 and in some cases again in 2006 and 2007: the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama (medical air evacuation squadron histories and Reba Whittle diary); the National Archives and the National Headquarters of the American Red Cross, both in Washington, D.C. (correspondence pertaining to the American Red Cross); and the Edward White II Aerospace Medical Museum (Hangar 9) located at Brooks Air Force Baselater Brooks City Basein San Antonio, Texas (documents about Elsie Ott). The Hangar 9 materials are now located at the Air Force Research Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton Ohio. Thanks also to staffs of the United States Army Medical Department Museum at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas (Leora Stroup papers) and the Bucyrus Historical Society in Bucyrus, Ohio (Lauretta Schimmoler papers) for permitting me access to documents and photographs held in their archives, and to the Oral History Research Office of Columbia University for granting me permission to cite and quote excerpts from Kenneth Leishs interview with Ellen Church in its collection. The staff of the Central Arkansas Library System interlibrary loan office was consistently helpful in locating published materials not available locally. I am also indebted to Ethel Carlson Cerasale and Helena Ilic Tynan, who let me reprint photographs from their private collections, and to Micah Jones and Robert Skinner, who clarified some research matters. Chris Robinson prepared the maps for the book. A special thank you goes to Joyce Harrison, acquisitions editor for Kent State University Press, for guiding this book through the publishing process with such grace and good will.