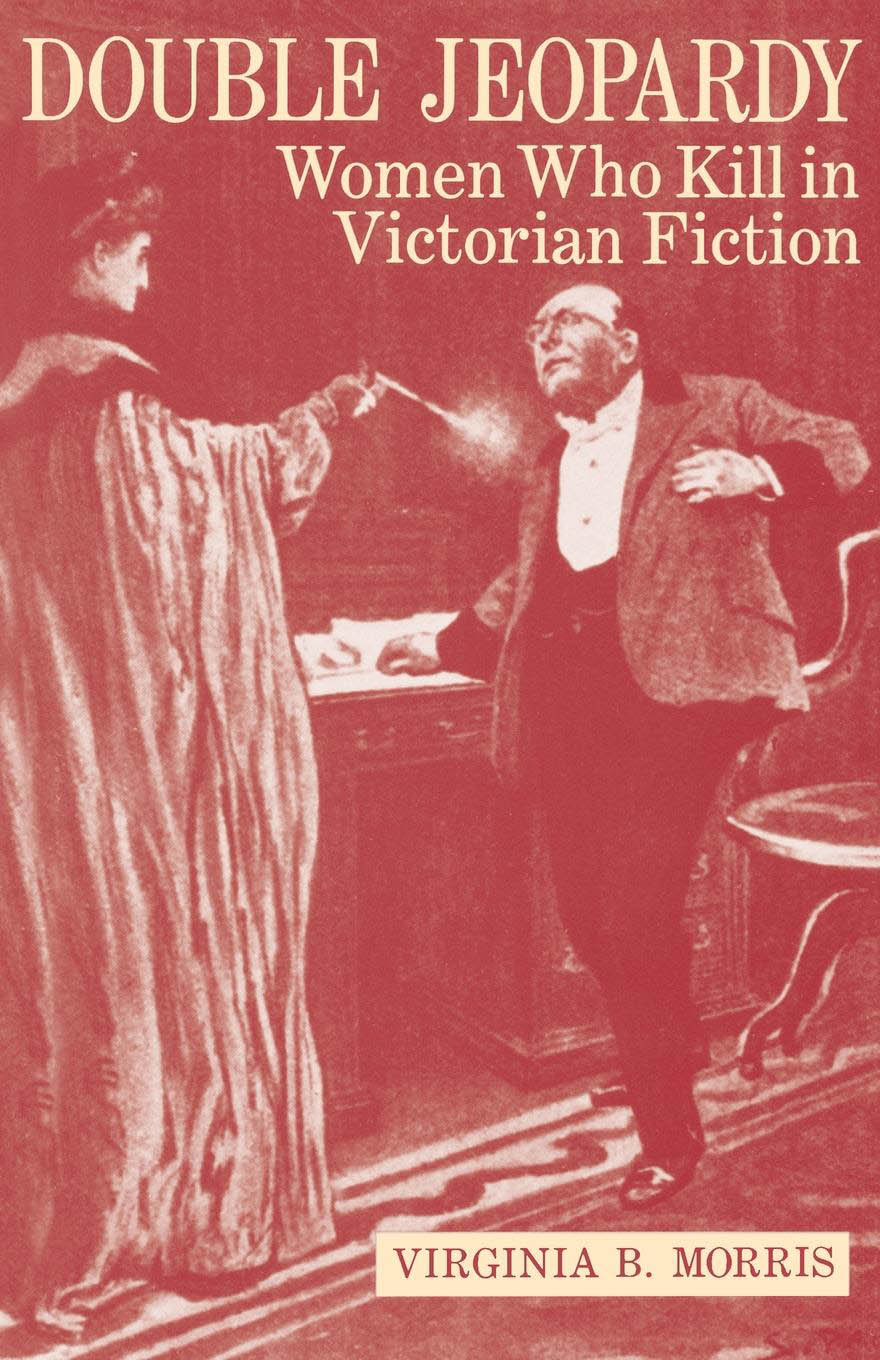

DOUBLE

JEOPARDY

DOUBLE

JEOPARDY

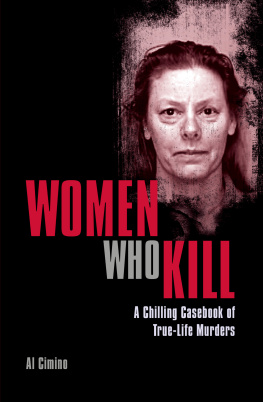

Women Who Kill

in Victorian Fiction

VIRGINIA B. MORRIS

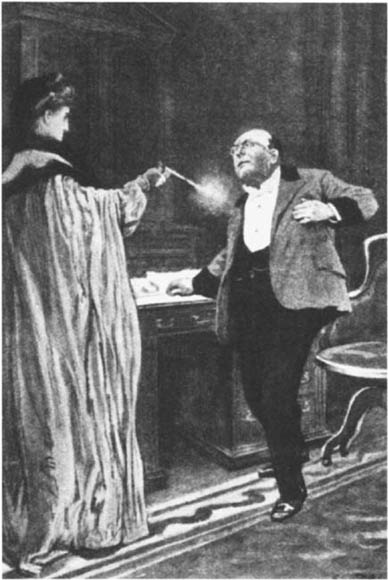

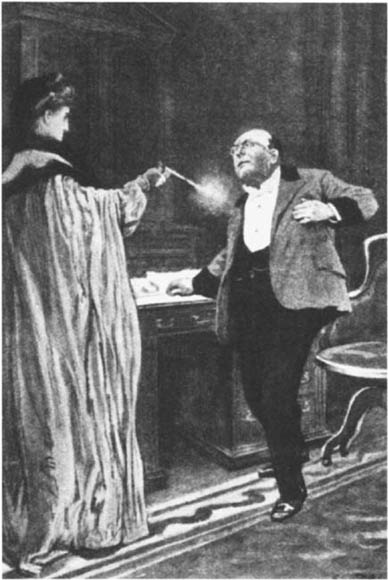

Frontispiece: Depictions of a womans violence were unusual in

Victorian fiction. This illustration showing an elegant and

determined Dark Lady in the act of shooting Charles Augustus

Milverton was a dramatic exception. Strand Magazine, 1904.

Copyright 1990 by the University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky

Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506-0336

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Morris, Virginia B.

Double jeopardy : women who kill in Victorian fiction / Virginia B. Morris.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-8131-5358-2

1. English fiction19th centuryHistory and criticism. 2. Women murdersPublic opinionGreat BritainHistory19th century. 3. Detective and mystery stories, EnglishHistory and criticism. 4. Women murderers in literature. 5. Trials (Murder) in literature. 6. Murder in literature. I. Title.

PR878.W6M67 1990

823'.809352042dc20 90-32879

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

For Ken

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My interdisciplinary interest in criminal justice and literature, which engendered the idea for this book, evolved from teaching at John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The enthusiasm of my literature students, the encouragement of my colleagues, and the financial assistance of the Research Foundation of the City University of New York sustained my commitment during the research and writing. I owe special thanks to Professor Robert Crozier, Elisabeth Gitter, Patricia Licklider, Barbara Odabashian, and Robert Pinckert.

The Womens Division of the American Society of Criminology has welcomed my participation in its multidisciplinary analysis of the subject of women and crime, and many Division members have generously shared their particular expertise. I have been enormously enriched by that association and I am grateful for it.

I would like to acknowledge the indispensable critical response of those anonymous readers who saw the evolving manuscript. Much of its strength is the result of their comments.

To Karen Halloran and Jane Driscoll, who put the first version on computer discs and then answered endless technical questions about how to work with them, my eternal thanks.

But without the boundless enthusiasm and merciless editing of my husband, Ken Morris, there would have been no chapters to type, no manuscript to read, no book to publish. To him, and to our daughters Courtenay and Mavis, I owe more than I can say.

INTRODUCTION

Twice Guilty: The Double Jeopardy of Women Who Kill

When women murdered in Victorian fiction, they struck home literally and metaphorically. Their victims were usually their husbands, lovers, or children; their crimes almost always occurred in a domestic setting. In committing murder, these otherwise ordinary women also struck hard at the cherished image of Victorian womanhoodthe gentle, nurturing guardian of morality and the home.

Violent crimes committed by women characters focused new attention on the motives for these desperate and unexpected acts. Even the most misogynistic reader had to acknowledge that women did not commit random murder. The simple equation linking unbridled sexuality to criminality did not explain the behavior novelists described any more than did dismissing guilty women as being too masculine. Instead, womens economic and emotional dependence on men, and mens physical and psychological dominance over women contributed to, even precipitated, their one shocking moment of violence.

The books of manners and morals written for womeneven those that acknowledged the discontent women had begun to express in the 1830s and 1840signored the repressed, and therefore dangerous, rage of many Victorian women. So did most of the fiction. But some English novelists who recognized the mounting tensions over the inequitable status of the sexes portrayed sympathetic criminal women in their fiction. In turn, the novels about violent women articulated a broad range of social problems that could, and did, lead to murder, problems that included discriminatory divorce legislation, mens physical abuse of their wives, and womens legal and economic subservience. There can be little doubt that the Victorian audience recognized the realism of the situations that the novelists described and the intolerable dilemma of the trapped woman even if they perceived each murderous action as the product of an isolated, individual moment of despair.

Mary S. Hartman observes in Victorian Murderesses that the events which prompted the rare real-life women to kill display a pattern which suggests that, far from committing a set of isolated acts, the women may all have been responding to situations which to some degree were built into the lives of their more ordinary middle-class peers. Middle-class women in particular, she says, read fictions with formulaic treatments of love and courtship, with marriage as an inevitable happy ending. Sexual compatibility and physical domination were not discussed in romantic fiction, where the problems of married life received relatively little attention. Novels with women killers, on the other hand, examined the disparity between the ideal world described in the romantic fiction and the reality of womens marital experience. None of these fictional killers has a tolerablelet alone happymarriage. Deprived of this measure of conventional success, the fictional womans options were comparable to those of her real-life counterpart: she could suffer passively or find some assertive way to resolve her dilemma.

The overwhelming majority, both in life and in fiction, chose to accept their plight. If they tried to ameliorate their situation, they generally avoided personal retaliation either by leaving the abusive environment outright or using whatever legal means they could muster to resolve the dispute. Both of these approaches had serious practical limitations, however, because few women had alternative places to escape to and the laws tended to support the authority of men. But some of the mistreated women, if they were not physically or emotionally debilitated by their experiences, responded by attacking their abusers. Victims-turned-aggressors were, occasionally, subtly lauded for their courage; in some circumstances the criminal nature of their actions was overlooked, excused, or even glorified as striking a blow for liberation. Although no women killers in Victorian literature were transformed by their crimes into cultural heroines, almost all committed more or less justifiable homicide. But the self-contradiction which lay behind Victorian attitudes toward womens criminality, the dichotomy between women as morally superior to men and yet in every other way inferior to them, was not resolved even in the most thoughtful fiction.