Creating a Bird-Watchers Journal

excerpted from Nature Journaling, by Clare Walker Leslie and Charles E. Roth

Introduction

Many of us are looking for ways to connect better with nature to learn its patterns, to help protect its inhabitants, to gain an understanding of what makes our own lives tick. Scientists since the dawn of the human mind have sought to know nature better, and to know their own selves better. Many of them went out with pen, parchment, paintbrush, and telescope to record their sightings. The nature journal has been the companion for every man, woman, child, and old sage with an insatiable curiosity about the natural world.

Creating a Bird-Watchers Journal is adapted in large part from Nature Journaling: Learning to Observe and Connect with the World Around You (Storey Books, 1998). Before we get down to the specifics of a bird-watching journal, lets focus for a moment on nature journaling.

You wont find the word journaling in your dictionary. It is a word we created as an action form of the noun journal. Simply put, nature journaling is the regular recording of observations, perceptions, and feelings about the natural world around you. That is the essence of the process.

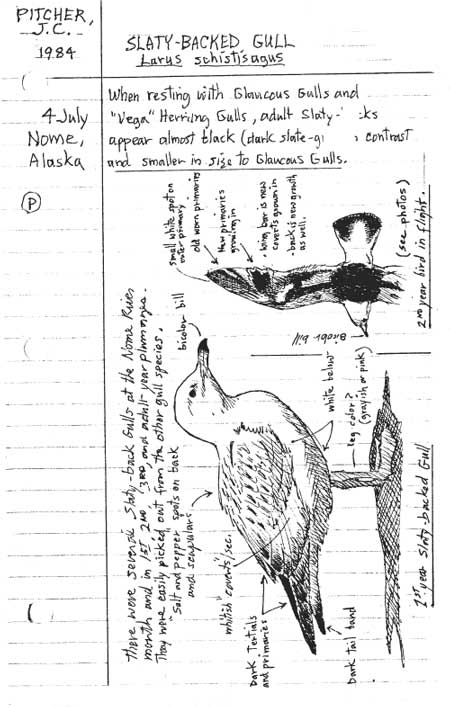

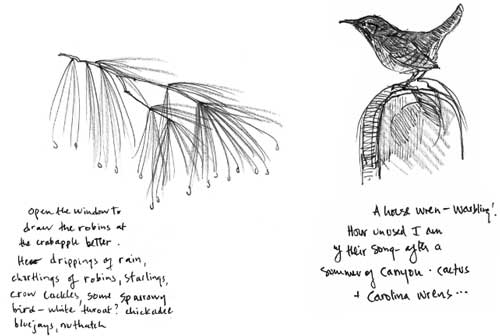

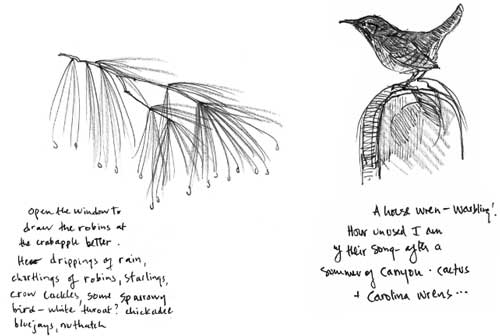

Journaling can be done in a wide variety of ways, depending on the individual journalists interests, background, and training. Some people prefer to record in written prose or poetry, some do it through drawing or painting, others with photographs or tape recordings, and still others through musical notation. There are people with the training and inclination to record with mathematical precision and in scientific shorthand. Some like to incorporate the writings and thoughts of others to stimulate their own journaling. Many people use all or a combination of these techniques.

Begin Exploring

Journaling is your path into the exploration of the natural world around you and into your personal connection with it. How you use your journal is entirely up to you.

You can be as involved as is your interest. Are you a classroom teacher, a self-taught and curious naturalist, an artist who loves nature, a scientist who would love to draw nature, someone who finds in nature a place for healing, meditation, and connection?

Go find a piece of paper; it doesnt matter what type or size. Find any pencil, marker, or drawing tool. Now open your eyes, take a deep breath, and ask yourself: What is happening outdoors, this particular season, this time of day, and in this particular place where I live? (You can be outdoors, or inside looking out.)

Draw a cloud, a bird flying by, a tree branch, ivy vines on a building wall, a potted plant, a garden flower. Dont judge your drawing. You are not an artist yet. You are a scientist, simply recording what you see, in this moment in time.

Be very quiet, be very still. Slow your breathing and think only bud, plant, bird. After one minute or less, no more, write what you drew and go on to the next sighting, keeping it relevant to season, time of day, and place. You have begun nature journaling.

A Flexible Medium

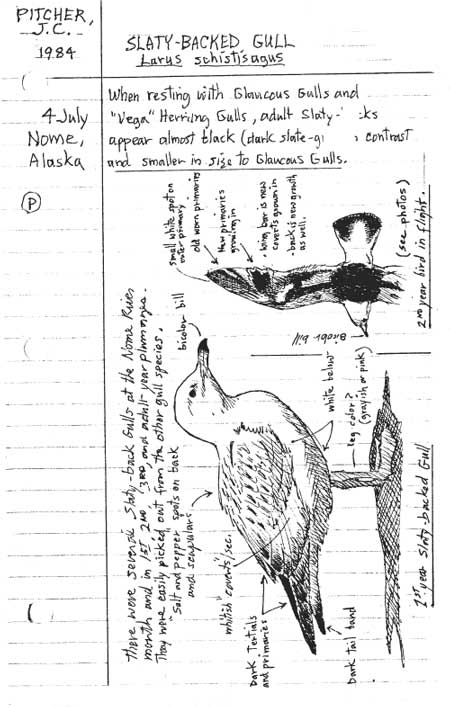

The appeal of the nature journal throughout the course of human history has been its flexibility. People have entered lists of birds seen at certain hours. Some count insects in a square yard of field and record their findings. Others keep moon-phase and weather charts. You can write poems, draw poems, or carefully diagram and draw a dead gull youve come upon on the beach. The journal is yours to use as you wish.

A Life Out-of-Doors

When I was young, I played outdoors all the time. Nature was a part of my daily world, as it was for my sisters and our friends. We never knew the specific names of things, but trees were towers to be climbed, bushes were caves, wooded paths were for bicycles, and creek banks were for endless games. Today those woods are gone, but I am the naturalist and artist I am now because of those magical days of play and camaraderie outdoors.

Now I teach and paint and write about the connections between drawing and nature. People ask where I began my study; it is too long a story to tell here, but it goes back to those woods.

I left for college and then to teach art and continue my training as a cellist. But the out-of-doors kept distracting me. I tried connecting the teaching of art with teaching about nature. It didnt work. So I quit to learn the path of a naturalist and a painter of nature on my own.

One day, canoeing with a friend across a wild stretch of open sea out to an island off the coast of Massachusetts to count migrating shorebirds, I knew I had found my way. A lone peregrine swept over us, swarming up a mass of dunlins that were feeding along the beach. I had my drawing pad and binoculars; I drew wildly in the rocking canoe.

And today I still have the print made from that startling event.

Clare Walker Leslie

For bird-watchers, a journal can become a personal course that is largely self-taught, or it may be simply a diary of sorts in which you record your birding adventures. This bulletin is not about a prescribed activity that is done in the same way by everyone; in fact it is about developing a very personal book, one that reflects the life around you the bird-watching experiences, encounters, reflections, and observations that you are moved to record, remember, study, and reflect upon.

Journals Help Science and Birds

Finding the Most Birds

Although you can travel widely to observe birds, you dont actually need to leave your own neighborhood. Your immediate area will provide a plethora of birds during the different seasons, according to the habitat each species requires.

Look for areas of transition from one kind of plant community to another; they tend to attract more birds of different species than do either of the separate communities. On the fringes of woods, for example, forest-dwelling warblers mingle with chickadees commonly seen at our feeders and in our shrubs. At the edges of swamps, shy woodcocks compete for earthworms with robins content to nest over our front doors.

Up until this century, field ornithology consisted primarily of exploration and classification. Classification usually meant the actual collection of nests, eggs, and even birds. It was an effective way to learn about birds but hardly beneficial to the birds themselves. Many keen birders collected all three types of specimens, often many sets of the same species. One source reports an individual who had 235 sets of robins eggs surely a case of more enthusiasm than good judgment. The modern technique of identifying birds by sight, using their size, shape, flight pattern, and so on as clues, makes a great deal more sense than shooting them does.