CRISPR: Genome Editing and Engineering: And Related Issues

Developmental Editor: Julie Mellors

Graphic Design Specialist: Kristine Julien

2018 Gale, A Cengage Company

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at Gale Customer Support, 1-800-877-4253.

For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions.

Further permissions questions can be emailed to permissionrequest@cengage.com

Cover image reproduced with permission of Meletios Verras/Shutterstock.com.

While every effort has been made to ensure the reliability of the information presented in this publication, Gale, A Cengage Company, does not guarantee the accuracy of the data contained herein. Gale, A Cengage Company accepts no payment for listing; and inclusion in the publication of any organization, agency, institution, publication, service, or individual does not imply endorsement of the editors or publisher. Errors brought to the attention of the publisher and verified to the satisfaction of the publisher will be corrected in future editions.

Gale, A Cengage Company

27500 Drake Rd.

Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535

978-0-0286-6668-6 (Consumer)

978-0-0286-6669-3 (Library)

Contents

Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering, History of

Around 1919, Hungarian engineer Karl Ereky (18781952) coined the term biotechnology to mean any product produced from raw materials with the aid of living organisms. Using the term in its broadest sense, biotechnology can be traced to prehistoric times, when hunter-gatherers began to settle down, plant crops, and breed animals for food. Ancient civilizations even found that they could use microorganisms to make useful products, although, of course, they had no idea that microbes were the active agents. About 7000 BCE, the Sumerians and Babylonians discovered how to use yeast to make beer, and wine making dates from biblical times. In about 4000 BCE, the Egyptians found that the addition of yeast produced a light, fluffy bread instead of a thin, hard wafer. At the same time, the Chinese were adding bacteria to milk to produce yogurt.

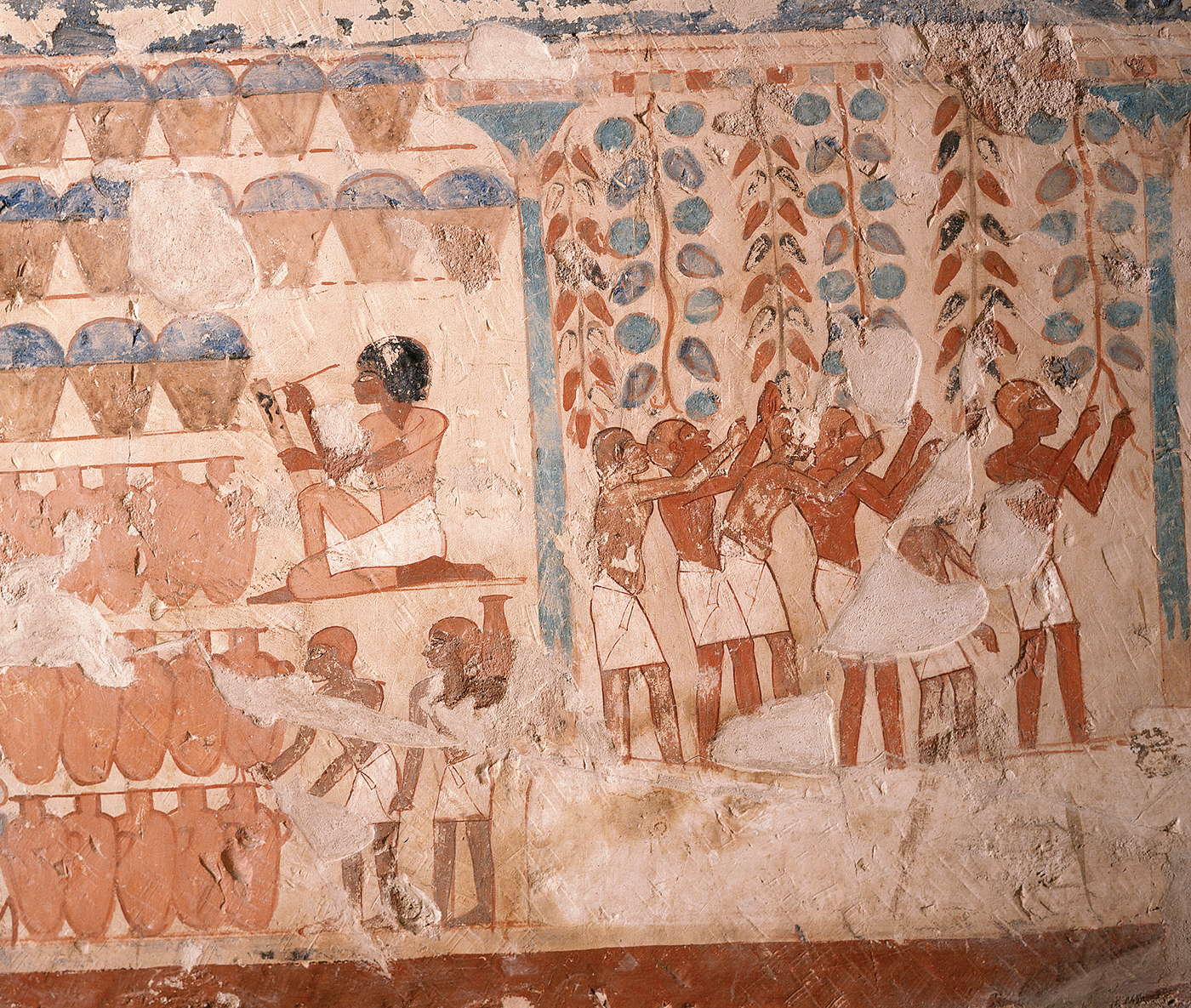

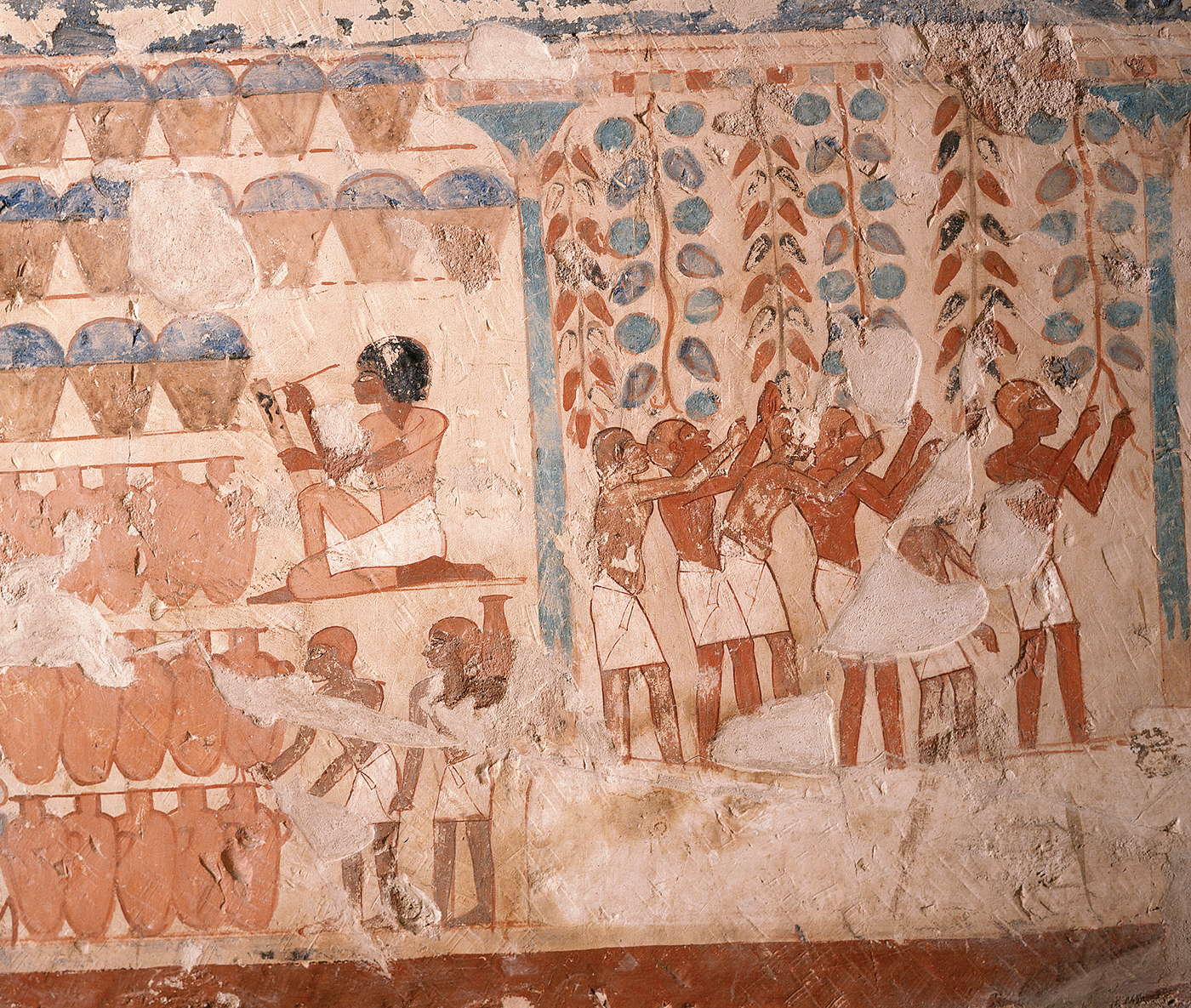

Egyptian artwork, dating from between BCE 1550 and 1295, depicts the harvest of the grapes and subsequent counting of the jars of wine. This art suggests that ancient civilizations fermented grape juice to make wine, establishing the basics of a process still used in wineries today.

De Agostini/G. Dagli Orti/Getty Images

Genetic Engineering versus Biotechnology

For many, the term biotechnology is often equated with the manipulation of genes, but as Ereky's definition suggests, this is only one aspect of biotechnology. For the more specific technique of gene manipulation, the term genetic engineering is more appropriate. Although the term was in use before the 1970s, genetic engineering is considered to date from that decade. At that time, molecular biologists devised methods to isolate, identify, and clone genes as well as to mutate, manipulate, and insert them into other species. One of the key elements in such research was the discovery of restriction endonucleases (restriction enzymes). These enzymes cut (cleave) DNA at a number of sequence-specific sites and often leave sticky ends. Isolated DNA from any organism could be cleaved with a estriction enzyme and then mixed with a preparation of a vector that had been cleaved with the same restriction endonuclease. By virtue of the sticky ends, a hybrid molecule that contained the gene of interest could be created, which could then be inserted into such a cloning vector. The importance of restriction endonucleases was recognized in 1978 when Werner Arber (1929), Daniel Nathans (19281999), and Hamilton O. Smith (1931) were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of these enzymes.

Further Advances and Ethical Concerns

The first experiment to combine different DNA molecules was performed in 1972 in the laboratory of Paul Berg (1926), who shared the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Walter Gilbert (1932) and Frederick Sanger (19182013) for their contributions concerning the determination of base sequences in nucleic acids. The following year, Stanley N. Cohen (1935) and Herbert Boyer (1936) combined some viral DNA and bacterial DNA in a plasmid to create the first recombinant DNA organism.

Realizing the potential dangers of moving genes from one organism to another, approximately 90 prominent scientists, whose laboratories were poised to start cloning experiments, met in 1975 at the Asilomar Conference Center in California to discuss the potential risks of gene manipulation. This meeting marked the first time that scientists openly discussed the consequences and potential dangers of their research before that research actually began. The result of the Asilomar Conference was a one-year moratorium before any cloning experiments were to be done. This provided time to develop guidelines for the physical and biological isolation of recombinant organisms, to prevent their escape into the environment, and, if they did escape, to make sure that they would be so weakened as to not survive competition with naturally occurring organisms. By 1976, gene cloning was in full swing around the world.

Illustration of recombinant DNA. The orange gene is not part of the original DNA but replaces a portion of the deleted original gene.

BSIP/JACOPIN/Medical Images.com

Key Technical Developments

Advances in biotechnology were marked by the development of key research techniques. In 1976, Boyer and Robert Swanson (19471999) founded Genentech, the first biotechnology company to use recombinant DNA technology to develop commercially useful products such as pharmaceutical drugs. The year 1977 is considered the dawn of modern biotechnology, because in that year the first human protein was cloned and manufactured using genetic engineering technology: Genentech reported cloning the first human hormone. The year was also important for the development of the technique of DNA sequencing, achieved by Sanger and Gilbert.

In 1978, Genentech isolated the gene for human insulin and began clinical trials that resulted in the approval and marketing of the first genetically engineered drug for human use. This was a major accomplishment. Diabetes, the seventh-leading cause of death in the United States, affects more than 30 million Americans. In the past, insulin was extracted from the pancreases of cows or pigs, then used to treat diabetics. Although insulin from these species is very similar to human insulin and was effective in humans, the small differences between human and animal insulin were enough to cause problems for some patients. Often, patients developed immunological reactions to the foreign protein, reducing its effectiveness. The availability of genetically engineered human insulin eliminated these problems.