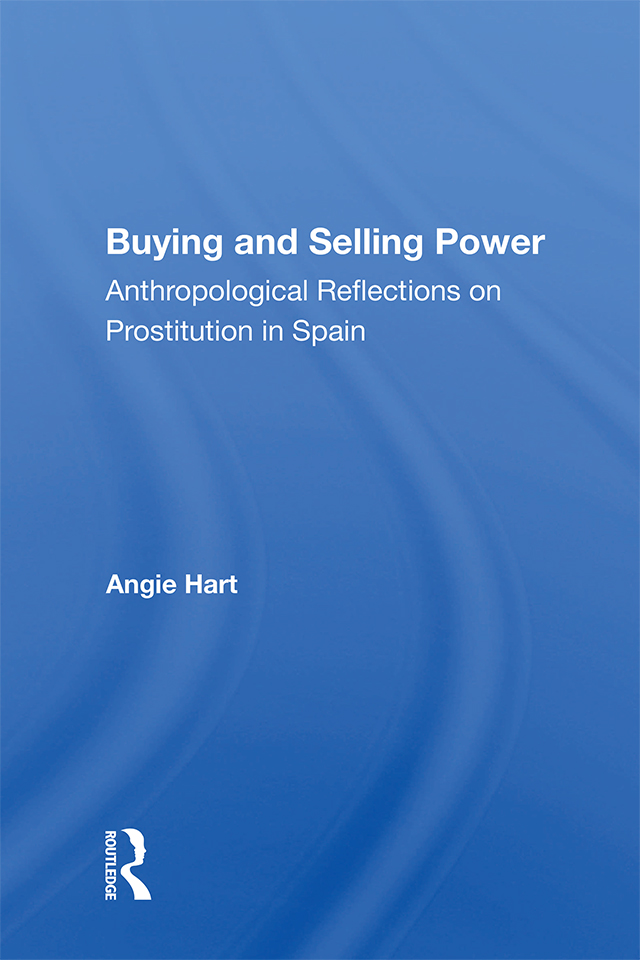

Studies in the Ehnographic Imagination

John Comaroff and Maurice Bloch, Series Editors

Reluctant Socialists, Rural Entrepreneurs: Class, Culture, and the Polish State Carole Nagengast

The Power of Sentiment: Love, Hierarchy, and the Jamaican Family Elite Lisa Douglass

Ethnography and the Historical Imagination John and Jean Comaroff

Knowing Practice: The Clinical Encounter of Chinese Medicine Judith Farquhar

New Worlds from Fragments: Film, Ethnography, and the Representation of Northwest Coast Cultures Rosalind C. Morris

Siva and Her Sisters: Gender, Caste, and Class in Rural South India Karin Kapadia

Articulating Change in the "Last Unknown" Frederick K. Errington and Deborah B. Gewertz

We All Fought for Freedom: Women in Poland's Solidarity Movement Kristi S. Long

The Time of the Gypsies Michael Stewart

Buying and Selling Power: Anthropological Reflections on Prostitution in Spain Angie Hart

First published 1998 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1998 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hart, Angie.

Buying and selling power: anthropological reflections on prostitution

in Spain / by Angie Hart.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-8133-3284-2

1. ProstitutionSpain. 2. Sex customsSpain. I. Title.

HQ226.H37 1998

306.74'0946dc21 97-3878

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-00982-3 (hbk)

At a job interview for a lectureship in an English provincial university, I was 'informally' chatting with the friendly, married Head of Department - I'll call him Fred. We were discussing my anthropological study of a small prostitution barrio (neighbourhood) in Marito, Spain. Fred was the second middle-aged male Head of Department I had spoken to at a job interview who knew the town in which I had conducted fieldwork and who knew the specific area in which I worked. As soon as he said that he knew Marito because he had been on holiday there, and that he knew the barrio I was gripped by boredom and a sense of dja, dja vu.

Respectable Fred introduced the topic to me thus: 'When we were looking at your job application, Angie, my colleagues said, "Ha, ha, we know why you went to Marito, Fred, ha, ha.'" I smiled, albeit weakly, because it was a job interview. "They said, "You know the area where Angie did research, don't you, Fred?"' Fred said to me (laughing), 'But of course I told them that I didn't know it in that way.'

The last time I had had this kind of conversation, at the previous interview, when the Head of Department had said that he did not know my fieldsite in that way, I had said 'You never know', implying that he might well have been a sex worker's client. This time I kept my mouth shut and simply smiled at Fred, trying to remember that this was a job interview. Inwardly I was seething. It seemed to me that yet again I was not being treated like a serious candidate.

This kind of predictable insinuation about heterosexual prostitution was not restricted to job interviews. It was a thoroughly unoriginal party piece, together with the line, 'I suppose you worked as a sex worker then', nudge, nudge, wink, wink, say quite a lot more.

It is difficult to convey the sense of frustration I feel at these kinds of conversations. In the case of Fred, I was not bothered about whether or not he had been to a sex worker. My work in Marito had really drummed home to me the fact that 'clients' were not just pejorative labels; they were human beings. I felt that being or not being a client was neither particularly remarkable nor particularly funny. Whilst I appreciated the value of small talk, this certainly did not seem like an appropriate conversation for a Head of Department to be having with me at a job interview. I was trying to get an academic job on the basis of my scholarly work. Yet I had to contend with smutty innuendo, disguised as middle-class niceties. Writing this, I almost feel as if I am exaggerating. The saddest thing is that I know I am not.

Trying to be amusing, people in a variety of different contexts ask me whether I worked as a prostitute in Marito. I take offence, not at the suggestion that I might have worked as a sex worker, but rather at the idea that it was something to be laughed about. Even though many people make this suggestion, it is usually clear to me that they never really think I had worked as a prostitute. They see the roles of academic scholar and prostitute as mutually exclusive. The fact that they can make jokes about it means that they do not believe I brought together these separate categories. I doubt whether most people would find it amusing if they seriously thought I had worked as a prostitute. I am sure they would see it as wholly inappropriate.

I would rather riot get too sucked into the 'Did she, or didn't she?' debate because these assumptions about my (non-)prostitute status are implicitly sexist and heterosexist. Nobody ever asked me, even in jest, if I had tried being a client. The question about my working as a prostitute often went hand in hand with an allusion to the (non-)client status of any male who happened to be in the room. At a middle-class 30-something house-warming party I spent much of my time avoiding the company of a woman - I'll call her Julie (about to do a degree in Social Policy after a course on Women's Studies) - who kept telling me and a number of the rest of the party that I must know the man she was talking to because he was one (i.e., a client). This was the first time I had met him and Julie. He looked embarrassed and rather puzzled. Julie tittered, obviously enjoying the situation. I felt weary because I had seen it all before and did not like it.

The books and supervisors say that fieldwork is overwhelmingly important in the development of an anthropological identity. In my experience, this turned out to be depressingly true. I seem to spend a lot of time running away from my 'anthropological identity' particularly at job interviews and at parties. Whilst generally speaking I try not to (and often cannot) go into the closet, I remember presenting myself in one context as a bilingual secretary because I could not be bothered with the jokes and the jibes.

Another popular line that people at job interviews and parties take on my work is that of 'You worked in a terribly dangerous area'. Fred, after expanding on his knowledge of Marito and its prostitution zones, informed me that his friends in Marito never went to this area. It was too dangerous to walk through. You got mugged, beaten up and hassled by prostitutes, pimps and drug pushers: 'I'm sure it was no place for a young girl [sic] to be doing fieldwork in.' My experience of working in the barrio was that it was dangerous, but not so terribly dangerous that one could not walk through it. And I felt that it was a perfectly appropriate place for me to be doing fieldwork. The point here is that Fred, with little knowledge of that location and little knowledge of my background, felt the need to lecture me on what was appropriate. The context in which he did this was tremendously important: the reader will remember that I was at a job interview for a social science lectureship. I felt that by pointing to my fieldwork location as inappropriate, Fred was, in a roundabout way, making judgements about my anthropological and personal identity. I had gone to the wrong place, done the wrong work, met the wrong people. Alas, a promising young female anthropologist and yet a tainted rose.