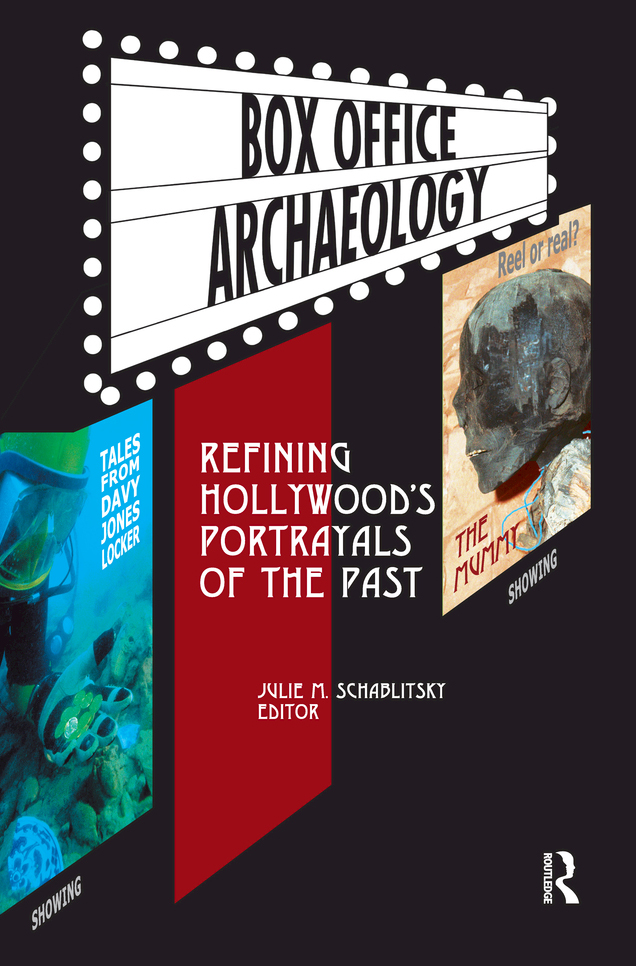

BOX OFFICE ARCHAEOLOGY

Box Office Archaeology

Refining Hollywoods Portrayals of the Past

Julie M. Schablitsky

Editor

First published 2007 by Left Coast Press, Inc.

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2007 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Cover photograph of John DeBry gathering artifacts from Richard Condents ship the Fiery Dragon which sank off Madagascar.

Photo by Nick Caloyianis courtesy of the Discovery Channel.

Cover photograph of mummy recovered from an excavation in the Theban necropolis. Photo by Stuart Tyson Smith.

ISBN 978-1-59874-055-4 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-59874-056-lpaperback

Contents

| Julie M. Schablitsky |

|

| Stuart Tyson Smith |

|

| Mark Axel Tveskov and Jon M. Erlandson |

|

| Charles R. Ewen and Russell K. Skowronek |

| James P. Delgado |

|

| Robert S. Neyland |

|

| Randy Amici |

|

| Charles M. Haecker |

|

| Paul R. Mullins |

|

| Rebecca Yamin and Lauren J. Cook |

| Julie M. Schablitsky |

| Bryn Williams and Stacey Camp |

|

| Vergil E. Noble |

Several years ago, I researched and excavated a 19th-century, ethnically heterogeneous, working-class neighborhood in Virginia City, Nevada. I had never watched the classic Western television series Bonanza but I knew the series was set in this world-famous mining district. After becoming intimate with the history of this once urban town, I watched a few episodes of Bonanza. The connection to the mining industry was tenuous and overshadowed by handsomely dressed cowboys and brightly colored Indians. Virginia City, Nevada, was only a backdrop to play out life lessons taught and learned by the affluent Cartwrights. From this experience, I became interested in the way history was collected for use in films and how gilded Hollywood history affected society.

To explore this interest, I organized a session, Screening the Past: An Archaeological Review of Hollywood Productions, for the Society for Historical and Underwater Archaeology Conference in York, England, in 2005. When archaeologists begin to explore their discipline's subject matter and its representation in popular culture, they are initially concerned with physical inconsistencies and facts. As expected, during the session many of us focused on older movies and Hollywood's telling of the past. Vergil E. Noble, one of the session discussants and chapter author, re-centered us through a discussion of the differences between archaeology and movies.

One comment, in particular, resonated with all of us, "Hollywood does not need to accurately tell a story if they can effectively teach the lesson." Since then, we have realized that archaeologists and Hollywood directors have different ways of delivering messages. Therefore, their stories need to contain certain elements (such as romance and violence), while purging others (ordinary people and the mundane). Archaeologists do not have the luxury of ignoring uninteresting or ambiguous information, so they can easily become excited by the discovery of a broken toothbrush.

On Thanksgiving Day, 2006, I watched an interview between Mel Gibson and ABC correspondents about Gibson's movie, Apocalypto. This production is based on the decline of the Mayans and their disturbing ritualistic response to an overstressed environment. To understand the Mayan culture, Gibson solicited the help of archaeologist Richard Hansen; however, not all of the professional guidance was followed in the movie. Toward the end of the ABC interview, Gibson revealed that Apocolypto held a lesson. The Mayans were guilty of using every resource from their environment and ultimately, conspicuous consumption led to their demise. The behavior of our modern culture, Gibson warned, is a mirror image of this ancient society.

Reflecting back, Vergil's revelation that Hollywood movies teach lessons is correct. The fact that archaeologists contribute detailed information needed to translate these lessons is also true. Although movies and archaeology have two separate purposes, they often tell the same stories, albeit in different formats. By the end of this book, I believe we will collectively realize that archaeology and Hollywood share common ground and perhaps this is why our conversation on movies began.

Chapter 1

The Way of the Archaeologist

Julie M. Schablitsky

No one should have illusions about television. It is never going to be primarily an educational and cultural medium.

Eric Sevareid (CBS correspondent, 1960)

Scholarship that focuses on the accuracy of Hollywood's portrayals of past events, places, and people is short sighted and ineffective at encouraging film producers to adhere to historical truths. For the past thirty years, historians have berated producers of movies and television shows for "getting it all wrong." Unlike modern movie budgets, television and movie production companies had limited funding, sets were simple, and intensive research on a historical-based story was the exception rather than the rule.

Today's Hollywood productions are savvy, the sets are impressive, and the wardrobes are impeccable. Movie producers take the time and allocate funding to hire historical consultants and employ prop masters to fine tune their sets. Before the film begins to roll, the actual setting is visited by production personnel; photos are taken, historical documents are copied, and historians and/or archaeologists are consulted. Within weeks, a mirror image of a historic town or building interior can be replicated from this research.

When Hollywood seeks out experts for use on the creation of their productions, they commonly solicit the knowledge of the amateur historian. Often, their published material is geared toward the public and their approach to the subject is filled with specific details rather than broad themes like those provided by professionals (Carnes 1996:21). When professional archaeologists are called on, they are used for specific aspects of the movie such as the reconstruction of lost languages. In other instances, their laboratories may be visited so that the film sets can be dressed with historically accurate tea sets, lighting, and decorative pieces.

A large part of this new attention to historic detail by producers is the direct result of a newly educated public. Active participation in historical reenactor groups, access to museums, and an increase in the number and variety of documentaries have created audiences who can discern between 19th- and 20th-century fashions and regional differences between American Indian homes. Although the cinematography and accuracy has dramatically improved over the years, filmmakers have not been inspired to capture an absolute past. Instead, Hollywood takes risks, pushes the envelope, and exercises creative liberties with our history. Unlike the archaeological community, their success is not measured by a scholarly panel but by the number of viewers who buy tickets and tune in to their stories.