ONCE AND FUTURE FEMINIST

Editors-in-Chief Deborah Chasman & Joshua Cohen

Managing Editor Adam McGee

Senior Editor Chloe Fox

Engagement Editor Rosie Busiakiewicz

Editorial Assistant Rosemarie Ho

Publisher Louisa Daniels Kearney

Marketing and Development Manager Dan Manchon

Finance Manager Anthony DeMusis III

Book Distributor The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts,and London, England

Magazine Distributor Disticor Magazine Distribution Services 800-668-7724, info@disticor.com

Printer Sheridan PA

Board of Advisors Derek Schrier (chairman), Archon Fung, Deborah Fung, Alexandra Robert Gordon, Richard M. Locke, Jeff Mayersohn, Jennifer Moses, Scott Nielsen, Robert Pollin, Rob Reich, Hiram Samel, Kim Malone Scott

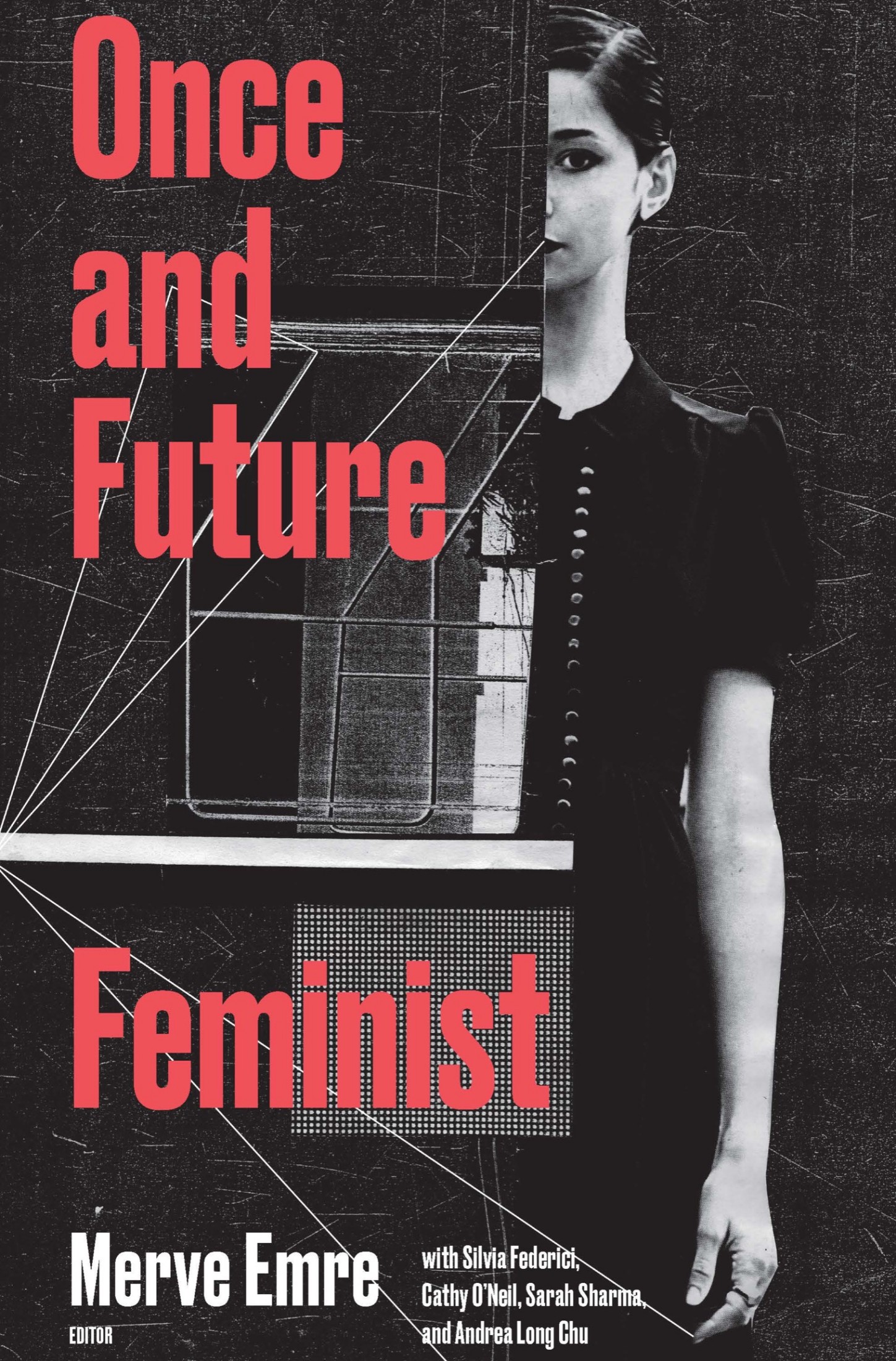

Cover and Graphic Design Zak Jensen

Typefaces Druk and Adobe Pro Caslon

Once and Future Feminist is Boston Review Forum 7 (43.3)

To become a member or subscribe, visit:bostonreview.net/membership/

For questions about membership and donations, contact: Dan Manchon, dan@bostonreview.net

For questions about subscriptions, call 877-406-2443 or email Customer_Service@BostonReview.info.

Boston Review

PO Box 425786, Cambridge, ma 02142

617-324-1360

issn: 0734-2306 / isbn: 978-1-946511-10-2

Authors retain copyright of their own work.

2018, Boston Critic, Inc.

d_r0

Deborah Chasman & Joshua Cohen

FORUM

Merve Emre

FORUM RESPONSES

Sophie Lewis

Annie Menzel

Chris Kaposy

Marcy Darnovsky

Irina Aristarkhova

Diane Tober

Miriam Zoll

Andrea Long Chu

Merve Emre

Silvia Federici interviewed by Jill Richards

Sarah Sharma

James Chappel

Cathy ONeil

Michael Bronski

Editors Note

Deborah Chasman & Joshua Cohen

How can women possibly be free if they must carry the burden of reproductive labor? In her The Dialectic of Sex (1970), radical feminist Shulamith Firestone raised this question and argued that technology could provide a promising answer: artificial wombs would provide a way out of a world of gender hierarchies. With the proliferation of assisted reproductive technologies such as egg freezing and surrogacy, it might look like we are making progress.

Merve Emre, our guest editor and lead author, is not so sure. Peoples bodies, she observes, are unruly sites for politics. Techno-utopias may have their attractions, but they flatten human life. Drawing on personal narratives, Emre explores how technologies shape real experiences of reproduction and care, and how they obscure and sometimes worsen inequalitiesin time, money, kinship, and access to healthcare. Such stories are heterogenous, individual, particular to place and person. Can an egalitarian and maximally inclusive feminism emerge from these stories? What would it look like?

Many of Emres respondents share deep concerns about the promise of techno-fixes: they turn pregnancy into a commercial transaction, transform babies into commodities, fetishize genetic perfection, echo histories of racial exclusion and state violenceor simply dont work. These critiques also suggestas does Emrerich sources for alternate visions, including the contributions of black women and queer communities in modeling and theorizing the kind of elective kinship and social structures that might sustain baby-making and distribute its burdens fairly.

With more than 2,000 kids forcibly separated from their parents, our current realities are painfully distant from these hopeful prospects. But utopian imagination is perhaps most important precisely when the gulf between real and ideal is greatest.

Other contributors to this issue also work at the rich intersection of technology, work, and feminism. James Chappel asks why feminist concerns are so rarely attentive to older womenwhose reproductive labor is finished and who are especially vulnerable in an economy with so much precarious work. Sarah Sharma looks to Silicon Valley and Mommy apps whose designs debase women by treating them as outmoded technologies. She asks how we might reimagine technology without gender hierarchies. In a speculative story on sex robots, Cathy ONeil gives us a glimpse of that future.

Finally, two contributors look back toward the future. Jill Richards interviews legendary activist Silvia Federici, a member of New Yorks Wages for Housework in the 1970s, about her vision of womens liberation. Michael Bronski recalls Gay Liberations vision of a society in which gay men and women raised children together. Building from the past and from the margins, they imagine a world more generous, decent, and humane than our owna society organized around elective kinship and the belief that our children are our common responsibility.

On Reproduction

Merve Emre

According to the New York papers, the first artificial womb was discoverednot inventedon the night of February 24, 1894, in a queer little shop on East Twenty-Sixth Street. The shops owner, a reclusive scientist named William Robinson, was roused from sleep by the personal physician of E. Clarence Haight, a Madison Avenue millionaire whose wife had died in childbirth and whose daughter had been born weighing less than two pounds. Desperate to save the baby, the physician begged Robinson to give him something to keep her warm. Robinson hurried to the back of his shop and emerged with what he called his artificial womb: a black steamer trunk with a sliding window cut into the lid, a cruder version of the infant incubators soon to debut at the Great Industrial Exposition of Berlin in 1896. The Little Tot Has Been Nearly Three Weeks in the Artificial Womb, and the Prospects Are That It Will Live to Begin Life in the Normal Way About Three Weeks More, reported the Daily News on March 16.

Like many advances in reproductive technology, the artificial womb lent itself first to speculative fiction, then to scientific research, and finally to feminist theory. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the artificial womb appeared in hundreds of pulpy newspaper stories and dystopian novels, including Brave New World (1932), in whichectogenesisthe development of embryos outside the uterusenables the mass production of human beings. In 1952 the New York State Medical Society started designing an artificial womb that doctors imagined as a goldfish bowl filled with chemical fluids, connected to a life-support machine, that would do the work of a human mother. They did not succeed, but in 1962, doctors at the Royal Caroline Hospital in Sweden announced that they had, unveiling their artificial womb that brought back to life babies born dead and, more horrifying still, babies legally aborted from their mothers. This was the same year that expectant mother Sherri Finkbine learned that the child she was carrying would likely be born with severe deformities; after a highly publicized request for an abortion was denied by her home state of Arizona, she flew to Swedento the same hospital where the artificial womb was being housedto terminate her pregnancy. In the face of growing outrage over restrictive abortion laws, the artificial wombs promise of creating life without any womans consent began to look increasingly dystopian. By the mid-1960s, research into artificial wombs sputtered and then died for a time.

It was not until 1970 that radical feminist Shulamith Firestone imagined a future in which technologies of artificial insemination, test-tube fertilization, artificial placentas, and parthenogenesis (virgin birth, she calls it in her manifesto