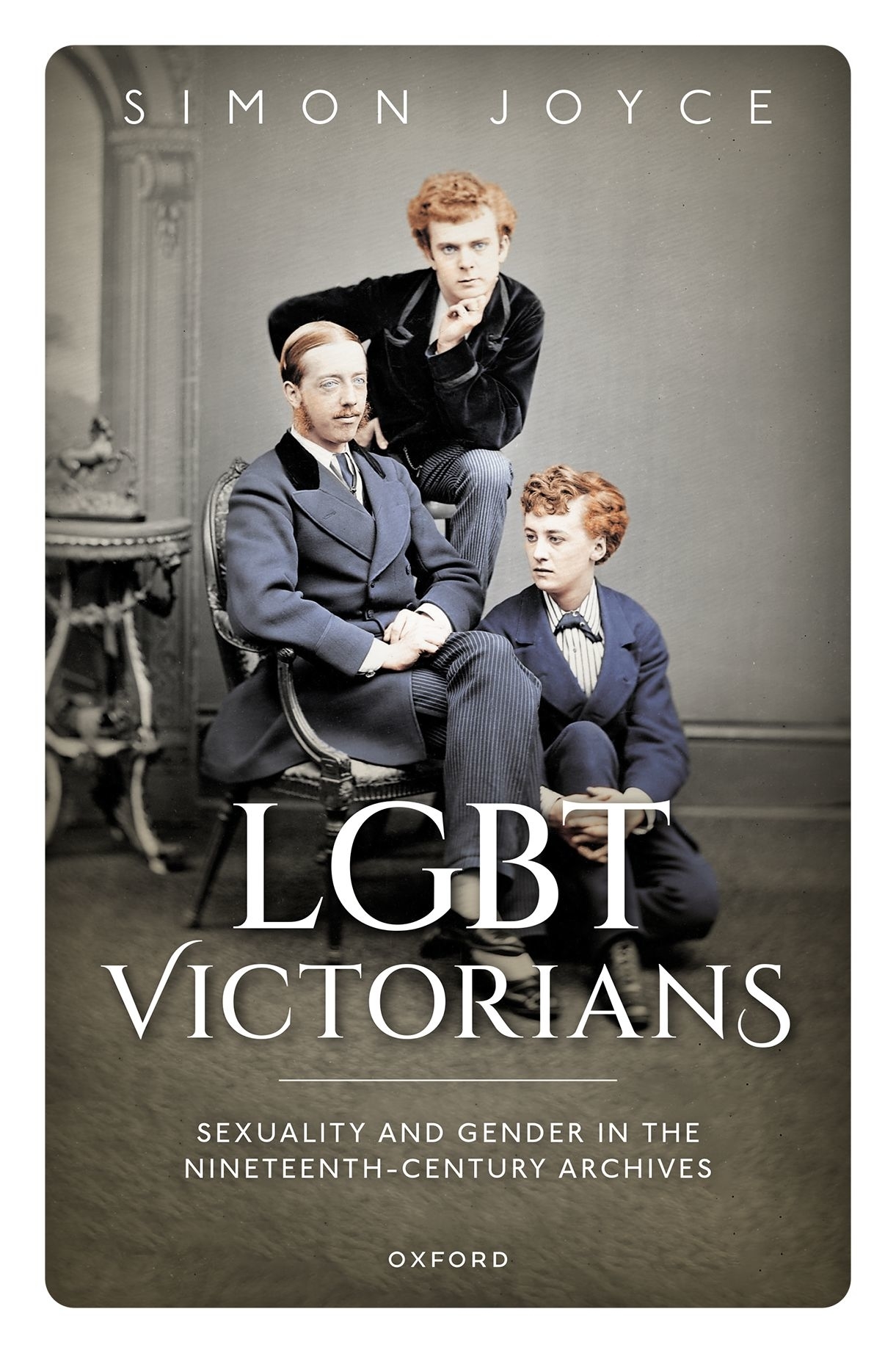

LGBT Victorians

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Simon Joyce 2022

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2022

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022932834

ISBN 9780192858399

ebook ISBN 9780192674203

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192858399.001.0001

Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books Limited

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Acknowledgments

If part of the purpose here is tell the origin story of the book, it has more than one, and perhaps as many as three points of departure. The most direct of these is that I see LGBT Victorians as a delayed follow-up to Victorians in the Rearview Mirror, in which I charted some of the afterlives of the nineteenth century in the culture and politics of the subsequent century. In that book I tried to understand and counter some of the hostility of twentieth-century modernism and highlight some still-positive aspects of the Victorian period. Its blind spot, as some reviewers pointed out, was its tendency to accept more or less at face value that on issues of gender and sexuality the Victorians have little to teach us. Correcting that assumption is one of the points of origin for LGBT Victorians. While Im thinking about the relationship between the two projects, let me also clarify something else they share, and that might trouble readers: in both cases, I use the term Victorian quite loosely, to designate a set of interlinked debates and competing positions through which we can come to understand a larger cultural formation. These can and do involve people who did not strictly live during the years of monarchical reign (including Anne Lister, who lived only a few years into the literal Victorian period) and sometimes in places other than the United Kingdom (such as the influential sexological writer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, who lived mostly in what is now Germany). Even more than the earlier book, I also want the word Victorian, with all of its everyday connotations, to jar when set against the more contemporarybut these days already slightly outmodedacronym LGBT, about which I say more in the introduction. One early working title was Learning from the Victorians about Sex, because I wanted (and still want) readers to wonder ifof all topicsthis is the last thing we can expect to learn about by studying the nineteenth century. If thats the case, I hope you think differently by the time youre finished.

Ive been fortunate and grateful to find a widening circle of people who like to think about such questions as well, sometimes in ways that I do and sometimes not. Some of these people are more interested in the relation between the Victorians and the modernists, some in the history of sexuality, some in aspects of LGBTQIA+ studies (to use a more up-to-date term), some in the individuals who are the focus of particular chapters of this book. Without trying to parcel out subgroups, I want to begin by registering my sincere and unending gratitude to the following fellow travelers: Cassius Adair, Joe Bristow, Colette Colligan, Renee Fox, Dustin Friedman, Ardel Haefele-Thomas, Lisa Hager, Diana Maltz, Kristin Mahoney, Deborah Morse, Mary Mullen, and Suzanne Raitt, who have all given me significant help and insights throughout the many years Ive been working on this book. My deepest gratitude also to Cathryn Steele at OUP, who has been a patient and considerate editor in these pandemic times, and three anonymous readers who made excellent suggestions for sharpening and clarifying parts of my argument that have all made this a stronger book.

My second point of origin might register that this work for me has involved learning, and sometime re-learning, how to think in different disciplinary subfields than those in which Ive tended to locate myselfin particular, a reorientation to a field of queer/lesbian and gay studies that bears little resemblance to the one I knew well back in the 1980s and 90s. In many ways, this book is a sorting through and coming to terms with those changes, and besides the people already named I want to express my gratitude to some institutional supports. Two important William and Mary colleagues, Tom Heacox and Terry Meyers, retired as I was writing this book, but their bold steps to break down the reflex conservatism of a Southern liberal arts college allowed my own work to happen with a minimum of friction by having already fought and won battles I didnt need to engage. I also want to thank the many students (but especially the queer, trans, and nonbinary ones) from whom I learned so much while I was teaching and working through this material, especially Meg Anderson, Kate Avery, Joel Calfee, Silvia Greer, Sam McIntyre, Cristina Sherer, and Halla Walcott.

Because this work required more time in various archives than I would typically need, I also want to acknowledge the institutional support provided by William and Mary, in research funds made available through the Margaret Hamilton professorship, the Plumeri Award for Faculty Excellence, and the Sara and Jess Cloud professorship, as well as a generous faculty sabbatical program. I have greatly appreciated the help, kindness, and expertise of the staff at the Kinsey Institute (Indiana University), the Public Records Office (Kew), the Edward Carpenter archives (Sheffield), Shibden Hall (Halifax), and all of those who are working on the Anne Lister diary transcription project, which continues to transform the ways we have thought about Lister. Many of these people also helped with supplying images for the book; others are reproduced here thanks to Lawrence Senelick, the Essex Record Office, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Henry Sheldon Museum. Between researching Lister and Edward Carpenter, I ended up spending a lot of thoroughly enjoyable time in Yorkshire; for making those trips so memorable, I want to thank Charlotte Booth and Tim Joyce, who has been almost like a brother to me for so many years now.

I also want to pay tribute to two wonderful teachers and mentors who died while I was completing this book and have influenced it in ways I can hardly count. The courageous and politically engaged example set by Alan Sinfield was a crucial gift from my years at the University of Sussex that is visible in the many ways that