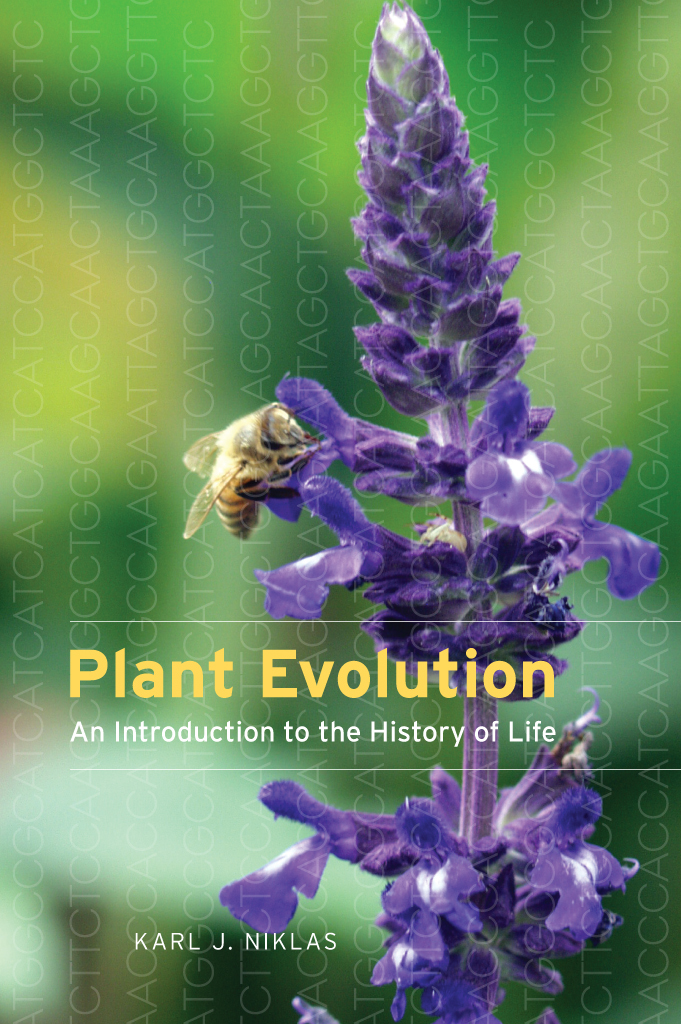

Plant Evolution

An Introduction to the History of Life

KARL J. NIKLAS

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

Karl J. Niklas is the Liberty Hyde Bailey Professor of Plant Biology and a Stephen H. Weiss Presidential Fellow in the Plant Biology Section of the School of Integrative Plant Science at Cornell University. He is the author of Plant Biomechanics, Plant Allometry, and The Evolutionary Biology of Plants, and coauthor of Plant Physics, all published by the University of Chicago Press.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-34200-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-34214-6 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-34228-3 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226342283.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Niklas, Karl J., author.

Title: Plant evolution : an introduction to the history of life / Karl J. Niklas.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016002294 | ISBN 9780226342009 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226342146 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226342283 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: PlantsEvolution. | Evolution (Biology)

Classification: LCC QK980 .N556 2016 | DDC 581.3/8dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016002294

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

CONTENTS

The thought we read is related to the thought which springs up in ourselves, as the fossil-impress of some prehistoric plant to a plant as it buds forth in springtime.

ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER, Parerga und Paralipomena (1851)

It is nearly two decades since the publication of The Evolutionary Biology of Plants and much has been learned in each of the scientific disciplines that contribute to our understanding of evolution and evolutionary theory. By necessity, therefore, Plant Evolution: An Introduction to the History of Life is a new book and not a second edition of my earlier work. To be sure, some of what is contained in the present volume draws heavily from my previous book. Although extensively rewritten, chapters provides a perspective on evolutionary ecology.

Like all of my other books, this one is personal and eclectic. Every book, no matter how technical, is a reflection of the authors mind, and Plant Evolution is no exception, since it is a distillation of what I consider to be significant concepts, principles, and facts. This book was written with a single purpose in mindto show why the study of evolution is important and why the study of plants is essential to understanding evolution. To paraphrase Theodosius Dobzhansky (19001975), if nothing in biology makes any sense except in the light of evolution, then nothing in evolutionary biology makes sense if not illuminated by studying plant biology. This claim rests on the fact that plants are very different from animals or fungi, yet much of the standard evolutionary literature is zoocentric. It is ironic to a botanist such as myself that biology textbooks sometimes begrudgingly treat plants as decorations on the tree of life rather than as the forms of life that allowed that tree to survive and grow. This is a blue planet, but it is a green world.

Plant Evolution does not provide a comprehensive overview of evolution. It is a collection of nine essays that attempt to cover the major lines of evidence that prove that evolution is factthat is, evidence from the fossil record, molecular biology, comparative embryology, comparative anatomy, comparative physiology, the experimental manipulation of species, and biogeography. No author can survive the pretense of claiming to understand everything about evolution, and no single book can delve into every aspect of evolution, even superficially. Each book can only bring a particular perspective to illuminate some corner of the history of life. My goal was to cover the fundamental processes of evolution from the perspective of a botanist who has enjoyed studying plants and who has tried to comprehend the breathtaking discoveries made about them over the past two decades. By way of inclinations and biases, you should know that I was trained first as a mathematician and second as a paleobotanist. As a student of numbers, I know that understanding evolution depends in part on understanding mathematics. I hold to the idea that if we cannot quantify something, we do not truly understand it. In addition, probability theory, the dynamics of changing gene frequencies, and many other aspects of evolutionary theory are mathematics in different guises.

But I am also a student of the dead. Knowing the fossil record is just as important as knowing about living organisms. If we neglect the past and study only the living, we would be totally ignorant of over ninety percent of all the species that ever lived and we would have no real insight into the causes and consequences of phenomena such as global climate change and mass extinctions. The study of the fossil record requires no apologyit is vital and important to every aspect of modern biology.

This book is intended to serve as the text for an upper-level undergraduate course, or as a text for an early postgraduate course. I freely admit that it is my intention to steer students toward studying plants professionally. For this reason, I have tried to keep the writing style of this book simple (albeit without sacrificing accuracy) and to use jargon sparingly. Jargon is unquestionably necessary at times. But technical words spoken glibly in the classroom or released on paper tend to sound like explanations rather than descriptions, and jargon in any form can easily mystify and alienate a student. Jargon has yet another negative aspectit can build walls around disciplines and thereby hide a disciplines relevance to other fields of study. Unfortunately, biology has more than its fair share of terminology. Consider for example that the basal body is called a kinetosome by the protozoologist, who calls the cell biologists undulipodium a flagellum, which is a very different structure from the flagellum studied by the bacteriologist. Likewise, what a phycologist calls siphonocladous, a bryologist calls symplastic, which is not to be confused with what the zoologist calls a syncytium. As these few but perhaps painful examples of terminology attest, the study of evolution, which employs the vocabulary of all of the scientific disciplines, involves learning the meaning of many technical terms. I have done my best to inflict as little pain as possible, and I have provided a glossary for some of the more troublesome technical terms (or those that I may have used idiosyncratically).

This book is intended as a textbook, or as a reading for a seminar; it was not written to cite the primary literature wherever a declarative sentence appears in the text. A few citations appear from time to time, but only when necessary to acknowledge the contributions of particular individuals. This tactic was predicated on the notion that libraries and Internet search engines are available to students. It was also based on the fact that the most recent literature is easily found on the Internet, whereas the older literature is more difficult to find electronically. A few key words, such as the name of a researcher, typed into the Internets vast resource network can locate the required new literature easily. Whether the literature found in this manner provides reliable information is another matter. Each of us must exercise great judgment when reading anything, including this book. In lieu of references in the text, a suggested reading list is provided at the end of each chapter. An emphasis is placed on the older literature, which is often neglected or forgotten. Even though one of my goals was to integrate the new discoveries made about plants with the literature published one or more hundred years ago, re-reading this older literature gives credence to the proclamation

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).