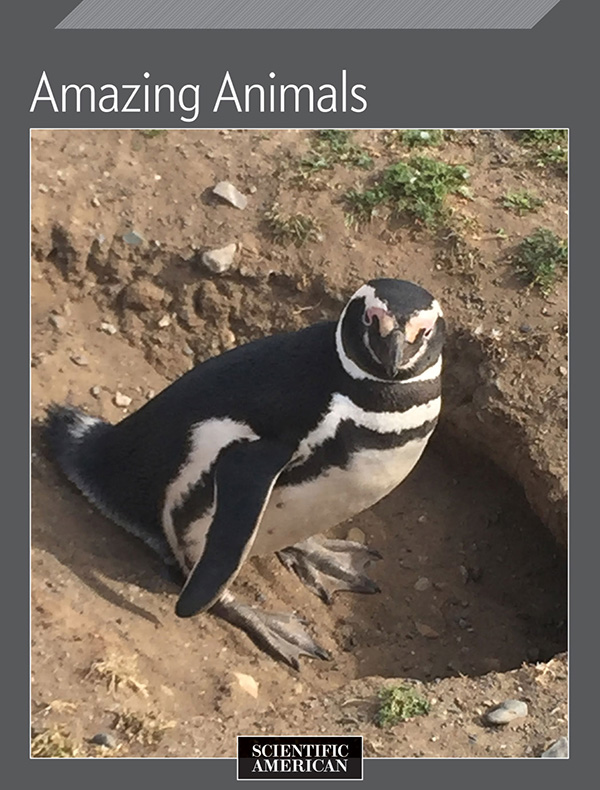

AMAZING ANIMALS

From the Editors of Scientific American

Cover Image: Lisa Pallatroni

Letters to the Editor

Scientific American

One New York Plaza

Suite 4500

New York, NY 10004-1562

or editors@sciam.com

Copyright 2017 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc.

Scientific American is a registered trademark of Nature America, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published by Scientific American

www.scientificamerican.com

ISBN: 978-1-2501-2156-1

AMAZING ANIMALS

From the Editors of Scientific American

Table of Contents

Introduction

by Andrea Gawrylewski

Section 1

1.1

by Ximena Nelson

1.2

by Rob Dunn

1.3

by Crispin T.S. Little

1.4

by Elizabeth A. Tibbetts & Adrian G. Dyer

1.5

by Emily V. Driscoll

1.6

by Christie Wilcox

Section 2

2.1

by Katherine Harmon Courage

2.2

by Carolynne K-lynn L. Smith & Sarah L. Zielinski

2.3

by Julie Hecht

2.4

by Barbara J. King

2.5

by Holly Dunsworth

Section 3

3.1

by Daniel T. Ksepka & Michael Habib

3.2

by Kenneth C. Catania

3.3

by Axel Meyer

3.4

by Rdiger Riesch

3.5

by Stephen Brusatte

3.6

by Josh Fischman

3.7

by Steve Mirsky

The Secret Lives of Animals

In Africa a species of termite builds columns of mud and spit, sometimes up to 18 feet tall. Paper wasps with brains the size of two grains of sand can recognizethe faces of their fellow wasps. On the seafloor, dozens of unique marine bacteria,worms and crustaceans make their homes within rotting bones of dead whales.Why do animals do such strange things? In this eBook, scientists offer answers to thisquestion. They also reveal surprising discoveries about how animals think and feel. And theyexplain how some of the oddest creatures ever to roam the earth came by their weird traits.

The animal behaviors that seem peculiar to us humans actually make a lot of sense for survival.Take, for instance, those termites. It turns out that their mud house is climate-controlledthe CO2 from the bugs respiration rises out of the top of the mound, whereas at nightthe outer chambers of the column let in oxygen to keep the critters from suffocating.Other insects have crueler survival tactics. The female jewel wasp injects venom directly intoa cockroachs brain to paralyze it, preserve it and feed it to her unborn spawn.

Humans tend to think that we are unique in our intelligence, social skill and depth of emotion.Yet we think too much of ourselves. The humble chicken, for example, is strikingly clever.Males secretly subvert the pecking ordergoing behind the back of their more dominantrivals to court females. Some wild animals even show whatcould be construed as grief: dolphins will carry the body of their dead calves with them, andelephants will revisit the bones of lost herd members for years after they die.

And then there are animals that are simply jaw dropping. The prehistoric bird Pelagornissandersi, with its 24-foot wingspanmore than twice the wingspan of the albatrosswas anunparalleled ocean soarer. And deep in the tunnels of wetlands, a tiny mole with afleshy, pink nose the shape of a star devours up to five items of prey a second.

Enjoy this tour of the secret lives of animals. My guess is that you will feel somewhat athome, even among the strangest creatures. After all, we are animals, too.

-Andrea Gawrylewski

Collections Editor

SECTION 1

The Wild Things They Do

The Spiders Charade

by Ximena Nelson

Imposters abound in the animal kingdom. Peruse any textbook descriptionof mimicryin which one species evolves to resembleanotherand you will encountervarious classic examples,such as the king snake, which copies the coral snake, or thehoverfly, which masquerades as a bee. Less familiar but in many ways even more fascinatingare the mimics in a genus of jumping spider known as Myrmarachne,which look for all the world like ants. Unlike other jumping spiders, with their furry, round bodies,Myrmarachne species have smooth, elongate bodies that give the appearance of having the threedistinct partshead, thorax and abdomenof ants, despite having just two.

To complete the charade, the spiders walk on their threerear pairs of legs and raise the fourth pair overhead, wavingthem around to simulate ant antennae. They even adopt antscharacteristically fast, erratic, nonstop mode of locomotion inplace of the stop-and-go movements other jumping spidersmake. It is an Oscar-worthy performance and the secret of thisgroups success: more than 200 species of Myrmarachnethrive in the tropical forests of Africa, Asia, Australia and the Americas.This rich diversity makes ant mimicry the most commonform of mimicry. Yet it is the least known.

New research is exposing the mind-boggling complexity ofthe ant mimics charade, however. Like the king snake and hoverfly,Myrmarachne species gain a survival advantage by lookinglike other speciesin this case, lethal ant species, becausepredators of spiders steer clear of both the ants and their look-a-likes.But, it turns out, the spiders pay for that advantage: togive a convincing performance, they must expose themselves toconsiderable risk. The evolutionary forces that led to their fakeryhave left the ant-mimicking spiders living on the knifesedge, walking a fine line between avoiding one enemy and fallingprey to another. In revealing the unexpected perils of mimicry,studies of these remarkable arachnids show the phenomenonof mimicry in a new light.

FAKING IT

My fascination with mimicry began one day in 1995 in theoffice of my then supervisor, Robert R. Jackson, while discussingpotential research topics for my masters degree. Jackson, aspider expert at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand,had cemented his reputation as a leading arachnologist throughhis work on Portia, a genus of jumping spiders renowned fortheir mammalianlike levels of clever behavior. Accordingly, hesuggested that I work on a species of Portia. As an afterthought,he mentioned the antlike jumping spiders found in the tropics. Iwas instantly intrigued. We eventually became colleagues, sharinga laboratory, and for 20 years we traveled throughout Africa,Australia and Asia to research these remarkablecreatures. Throughout our journeys we have discovered many unusualconsequences of mimicry that underscore just how much morecomplicated the business of deception is than conventional wisdomwould suggest.

The standard view originated with English naturalist HenryWalter Bates, who in 1861 provided the first scientific theory toexplain mimicry in nature, based on his observations of Amazonianbutterflies. Bates supposed that an edible species thatresembled an unpalatable or downright toxic one would gain asurvival advantage by tricking potential predators into leavingit alone. In Batess scenario, predators would learn from experiencethat eating the nasty species was a bad idea. After thatunpleasant encounter, the predators would avoid the toxic speciesand would then avoid the mimics, tooeven though themimics themselves were harmless. This parasitic charade, inwhich one species exploits anothers defenses, is now known asBatesian mimicry.