Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

METHUSELAHS ZOO

What Nature Can Teach Us about Living Longer, Healthier Lives

STEVEN N. AUSTAD

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Steven N. Austad

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Austad, Steven N., 1946- author.

Title: Methuselahs zoo : what nature can teach us about living longer, healthier lives / Steven N. Austad.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: A natural history of longevity in a wide variety of species along with an exploration of what we can learn from other species to preserve and extend human healthProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021049887 | ISBN 9780262047098 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: AnimalsLongevity. | Longevity. | AgingPrevention.

Classification: LCC QP85 .A97 2022 | DDC 591.4dc23/eng/20211221

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021049887

d_r0

To Veronika, who understands

Contents

List of Illustrations

Ornithologist George Dunnet in 1951 at age twenty-three and 1986 at age fifty-eight. The same bird is shown in both photos. Dunnet died in 1995. The bird was last seen the year after his death. Source: Photo courtesy of the Outer Hebrides Natural History Society.

Old Tjikko, the worlds oldest known tree in all its scraggly glory. The text explains why Old Tjikko, despite its age, is unlikely to teach us much about healthy aging. Source: Photo courtesy of Petter Rybck.

Longevity and the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) migration. Virtually no insects perform regular two-way migrations as do many bird species. Monarchs of the eastern United States are an exceptionan exception that illustrates an intriguing longevity pattern. After wintering in colonies of millions in central Mexico, they begin a multigenerational northward migration. The overwintering generation lay eggs in Texas and Oklahoma and then dies. The new generation continues north, living a couple of months before laying eggs and dying, handing the baton, so to speak, to yet another short-lived generation. This generation continues north, lays eggs, and like its parents dies after a short couple of months. But these eggs are different. Whereas the other generations live only about two months as adults, this generation will survive as long as eight months, fly several thousand miles back to Mexico, live through the winter, and then head north again in the spring. A key to this remarkably longevous generation is that they hormonally shut down their reproductive activity for the first six months or so of their adult lives. It is reproduction that apparently limits their longevity. The presence or absence of a substance called juvenile hormone is what turns reproduction and aging on and off. Sources: W. S. Herman and M. Tatar, Juvenile Hormone Regulation of Longevity in the Migratory Monarch Butterfly, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 268, no. 1485 (2001): 25092514. Figure modified with permission from Journal of Experimental Biology.

Pterosaur size and flight. All pterosaurs, even the largest species, apparently could fly. Among the largest were Hatzegopteryx (middle) and Aramourgiania (right). The giraffe and human are shown for scale. Source: Drawing courtesy of Mark Witton.

Cookie, a Major Mitchells cockatoo, the worlds longest-lived bird, still looking fit and alert at age eighty-one. Birds are famous for maintaining health until almost the end of their lives. Cookie lived to age eighty-three, and in his later years, Chicagos Brookfield Zoo threw him a birthday party each year. Source: Photo courtesy of Chicago Zoological Society/Brookfield Zoo.

Wisdom, the oldest known wild bird, shown here tending her egg just before her sixty-eighth birthday. Note her identification band (right leg). Currently at least seventy years old, she is still churning out chicks.

Indian flying fox with pup. The rigors of flight while carrying large pups during pregnancy or even after birth combined with the extra food demands to feed a growing pup may play a role in male bats often being the longer-lived sex.

The elephant bird (Aepyornis), an extinct island giant of Madagascar, compared to ostrich, human and chicken. The also extinct giant moas (not shown) of New Zealand were considerably taller but not as heavy as the elephant bird. All giant island bird species became extinct in historical times. Source: Drawing by De Agostini via Getty Images.

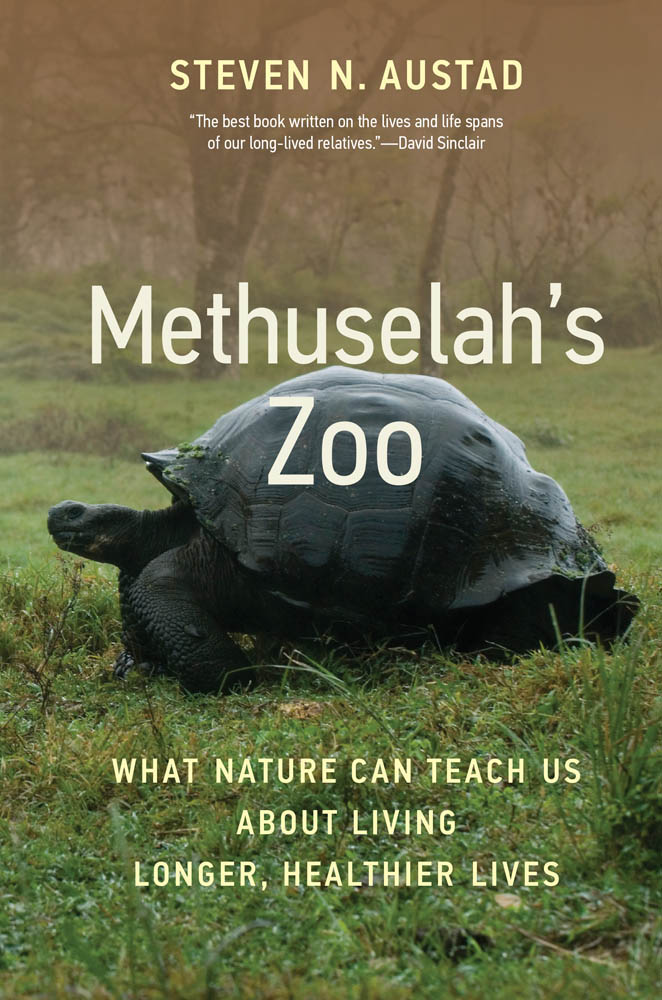

Jonathan, an Aldabra giant tortoise still living on the island of St. Helena, often erroneously called the worlds oldest animal. This photo of Jonathan, the tortoise on the left, has variously been claimed to have been taken in the 1860s, in the 1880s, and in 1902 or around 1900 (a cropped version showing only Jonathan and the two men standing behind him). As of March 2021, Jonathan was reputedly still alive. Jonathan is clearly very old, but any exact age is pure speculation or perhaps wishful thinking.

The tuatara is not a lizard. It is an ancient reptile that diverged from snakes and lizards 250 million years ago. The name means spines on the back in the Mori language. The slowest-growing reptile is one of the longest-lived species as well. This is an 1886 engraving. Source: Photo by George Bernard/Science Photo Library.

Size variation in imported red fire ant workers (circle) and queen (right). Larger workers live longer than smaller workers, but the queen can live twenty-five times as long as even the largest worker. Source: Photo courtesy of S. D. Porter.

A thirty-seven-year-old naked mole-rat in all its charismatic glory. About the same size as a mouse, naked mole-rats live up to seventeen years in the wild but more than twice as long in the laboratory. According to Rochelle Buffenstein, this same animal was still alive at thirty-nine years of age. Source: Photo courtesy of Rochelle Buffenstein.

The olm or human fish. With its absurdly slow life style, they mate every dozen years or so. One individual was found in the exact same spot it was originally captured after seven years. Adults are about twenty centimeters (eight inches) long, including the tail. Source: Courtesy of Shutterstock.

Barbara, one of the oldest-known African elephants. Part of the Amboseli elephant project, she was estimated to be sixty years old when this photo was taken. She died in 2020 at the estimated age of seventy-two years. Source: Photo courtesy of Phyllis C. Lee, Amboseli Trust for Elephants.