Also by Steven Johnson

Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate

Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software

Mind Wide Open: Your Brain and the Neuroscience of Everyday Life

Everything Bad Is Good for You: How Todays Popular Culture Is Actually Making Us Smarter

The Ghost Map: The Story of Londons Most Terrifying Epidemicand How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World

The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America

Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation

Future Perfect: The Case for Progress in a Networked Age

How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World

Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World

Farsighted: How We Make the Decisions That Matter the Most

Enemy of All Mankind: A True Story of Piracy, Power, and Historys First Global Manhunt

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2021 by Steven Johnson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Riverhead and the R colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

The PBS Logo is a registered trademark of the Public Broadcasting Service and used with permission. All rights reserved.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following images:

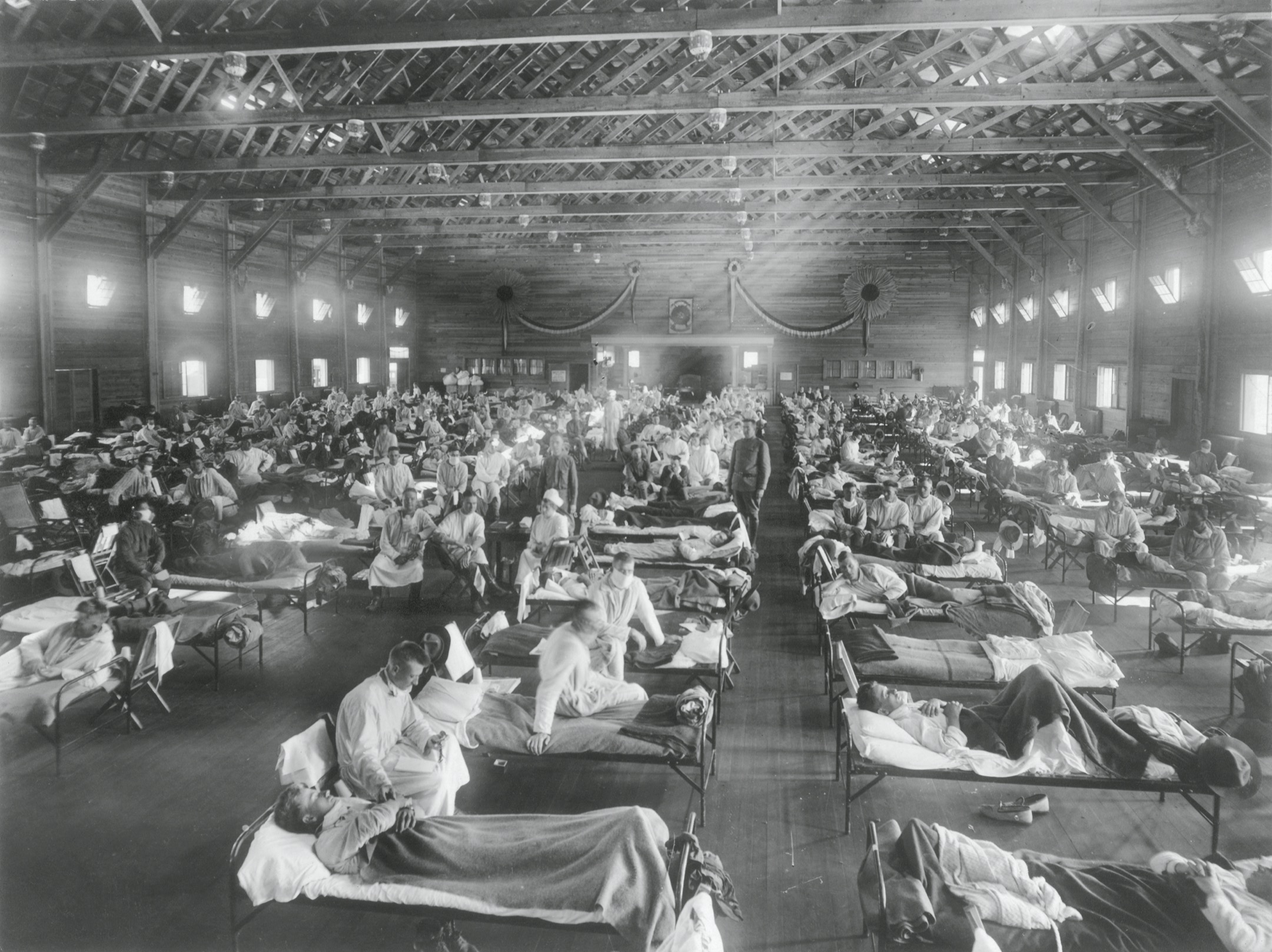

: Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas (NCP 001603). OHA 250: New Contributed Photographs Collection. Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

.

: Photo of replica of Heatleys apparatus for the extraction and purification of penicillin courtesy of the Science Museum / Science and Society Picture Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Johnson, Steven, 1968 author.

Title: Extra life : a short history of living longer / Steven Johnson.

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020033229 | ISBN 9780525538851 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525538875 (ebook)

Subjects: MESH: Public Health Practicehistory | Life Expectancyhistory |

Delivery of Health Carehistory | Socioeconomic Factorshistory |

Technologyhistory

Classification: LCC RA418 | NLM WA 11.1 | DDC 362.1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020033229

Book design by Meighan Cavanaugh, adapted for ebook by Maggie Hunt

Cover design: Gregg Kulick

pid_prh_5.7.0_c0_r0

For my mother

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

TWENTY THOUSAND DAYS

The stretch of the Kansas River just north of the town of Junction City has military roots that date back to 1853, when a post was established to protect travelers heading west in the years after the California gold rush. Within a few decades, the site became known as Fort Riley, and for a time it hosted the United States Cavalry School. In 1917, as the armed forces began preparing for the American entry into World War I, a small city with a population of fifty thousand was erected practically overnight to train Midwestern soldiers headed overseas to fight in the Great War.

Camp Funston, as it was called, contained around three thousand temporary buildingsthe predictable barracks and mess halls and commanders offices, but also general stores, theaters, and even a coffeehouse. The pop-up city had meaningful amenities for the young recruitsone soldier wrote home with an account of hearing a symphony entertaining the troops at Camp Funstonbut the temporary nature of the structures meant that most of the quarters were barely insulated. The first winter of the camps existence was an unusually frigid one, forcing the soldiers already bunked together in tight quarters to cluster even closer around the stoves in the barracks and the mess halls.

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas, 1918

As winter drew to a close in early March 1918, a twenty-seven-year-old private named Albert Gitchell presented himself at the infirmary complaining of muscle pain and fever. Gitchell was a butcher by trade, and had been serving as a mess cook at Camp Funston, preparing food for hundreds of his fellow soldiers in training. Doctors diagnosed his illness as influenza and dispatched him to the contagion ward in hopes of preventing the spread of the disease, but the intervention proved to be too late. Within a week, hundreds of other residents of Camp Funston reported influenza symptoms. By April more than a thousand soldiers at Camp Funston had been hospitalized. Thirty-eight of them died, a surprisingly high number for a disease that usually threatened only the very young and the very old.

The crowded infirmaries and the bodies piled in the morgue at Camp Funston were early clues that something unusual was happening at that Kansas army base. But what was really happening there would not be visible to scientists until the development of electron microscopy decades later. Inside the lungs of Albert Gitchell, a sphere covered in spikes fastened itself to a cell lining on the surface of the young privates respiratory tract. The sphere burrowed through the cell membrane into the cytoplasm, fused its own limited strand of genetic code with Gitchells, and began making copies of itself. Within about ten hours, the cell was teeming with newly replicated spheres, stretching the membrane to a breaking point, until, in one catastrophic instant, the cell exploded, releasing hundreds of thousands of new spheres into the mess cooks respiratory tract. Some of those spheres were coughed or sneezed into the air of the mess hall and the barracks. Others remained in the lungs of private Gitchell, latching onto other cells with the same brutal machinery of self-replication.

The doctors at Camp Funston had no way of knowing it at the time, but those spheres attacking Albert Gitchells lungs constituted a new strain of the H1N1 virus that would come to terrorize the entire world over the next two years in the pandemic commonly referred to as the Spanish flu. Just as the virus itself replicated in the respiratory tracts of the soldiers, the scene at Camp Funston would be replicated at military bases around the globe in the coming months, fueled by the steady flow of soldiers across the United States and onto the European front lines. American troops brought the virus to the military port at Brest, on the northwest edge of Brittany in France; the virus then erupted in Paris in late April. Italy soon followed. On May 22, the Madrid newspaper