VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

First published in the United States of America by Viking,

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2023

Copyright 2023 by Steven Johnson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Viking & colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us online at penguinrandomhouse.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data

Names: Johnson, Steven, 1968 author. Title: Extra life : the astonishing story of how we doubled our lifespan / Steven Johnson. Description: New York : Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2023. | Includes bibliographical references and index.| Audience: Ages 812 | Audience: Grades 46 | Summary: Humans live longer now than they ever have in their more than three hundred thousand years of existence on earth. And most (if not all) of the advances that have permitted the human lifespan to double have happened in living memory. Extra Life looks at vaccines, seat belts, pesticides, and more, and how each of our scientific advancements have prolonged human life. This book is a deep dive into the sciencesperfect for younger readers who enjoy modern history as well as scientific advancesProvided by publisher. Identifiers: LCCN 2022021894 (print) | LCCN 2022021895 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593351499 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593351505 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Health expectancyHistoryJuvenile literature. | Medical careHistoryJuvenile literature. | Life expectancyHistoryJuvenile literature. | Medical sciencesHistoryJuvenile literature. | TechnologyHistoryJuvenile literature. Classification: LCC RA418 .J588 2023 (print) |LCC RA418 (ebook) | DDC 614.4/2dc23/eng/20220617 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022021894 LC ebook record available at htps://lccn.loc.gov/2022021895

Ebook ISBN 9780593351505

Cover art courtesy of Monique Sterling

Cover design by Monique Sterling

Edited by Ken Wright and Catherine Frank

Design by Monique Sterling, adapted for ebook by Andrew Wheatley

This is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

pid_prh_6.0_142201953_c0_r0

For my mother

INTRODUCTION

It may not feel like it if you check the news, but you are living in a world that is far safer than the one in which your great-great-grandparents lived. Countless everyday experiences that used to pose terrible threats to our lives now pose no meaningful health risk at all. That glass of milk you had with dinner last night? A little more than a century ago, it might have contained germs that could cause the deadly disease tuberculosis. The scrape on your knee from falling off your longboard? That might have triggered a fatal infection just eighty years ago. Driving a car is ten times safer than it was when people first got behind the wheel.

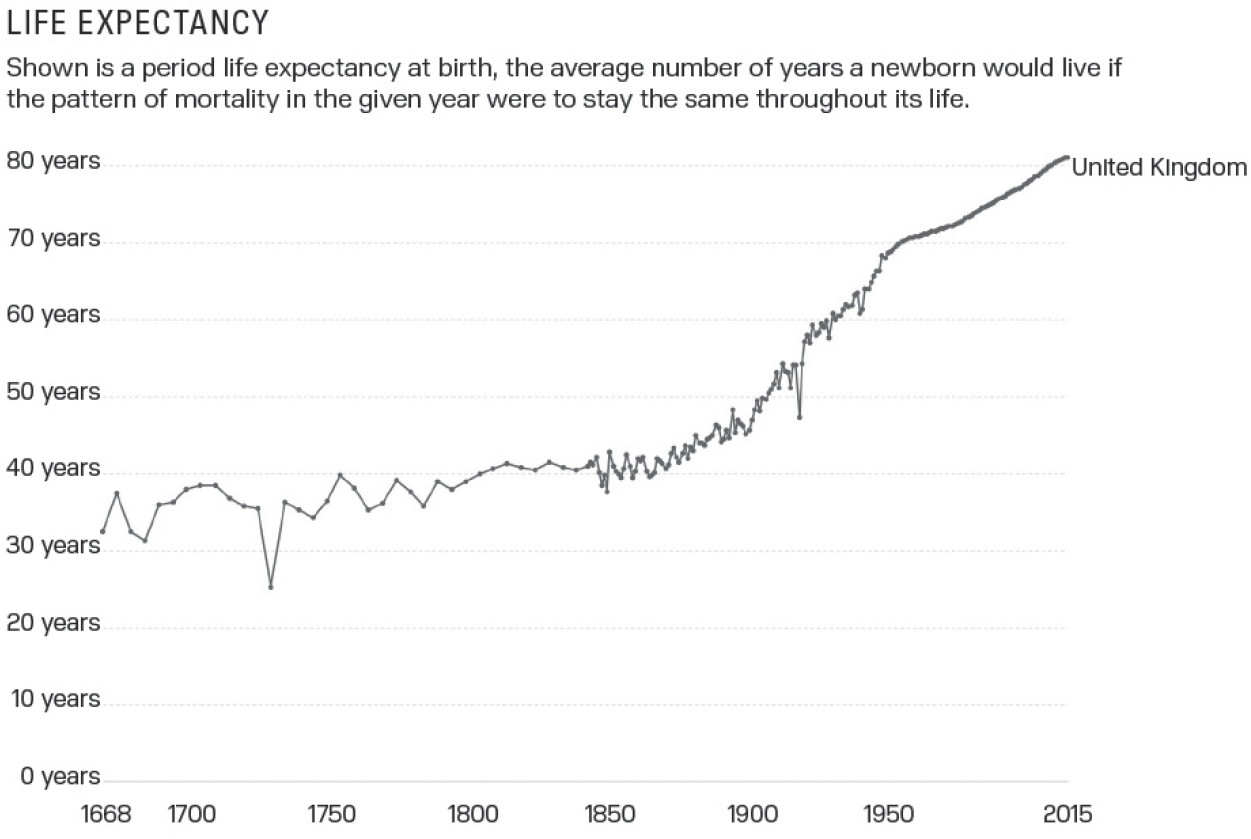

There are a thousand other improvements in health and safety like these, but they all add up to one amazing statistic, maybe the most important statistic of all. Its what we call life expectancy: the number of years that the average person born at a given place and time can expect to live. Take a look at this chart of life expectancy in the United Kingdom, where they have been measuring it the longest:

The average person born in the United States a century ago could expect to live a little more than forty years. Today that number is just below eighty years. And Americans are four times more likely to live into their hundreds than they were a few decades ago. Its an incredible transformation, and its not just happening in wealthy countries like the United States or the United Kingdom. A hundred years ago, life expectancy in India was only twenty-five years. Now its seventy years. As a species, its as though weve been given an entire extra life to live, compared to our ancestors.

Some of that extra life is the result of elderly people living longer. Think about your own extended family. Many of us have grandparents or great-grandparents who are in their eighties or nineties. Living that long is normal now. But it didnt used to be.

Another major factor in the story of life expectancy is how it changed what it means to be a child. For most of human history, about a third of all children died before they turned eighteen. Today its closer to one in a hundred.

So why isnt the story of extended life something we hear about all the time? Why isnt it front page news? Because, most of the time, it doesnt involve the sudden, dramatic changes that draw media attention. The changes that made our world so much safer were subtle, incremental ones. They were slow and steady. In the long run, they add up to the most momentous transformation you could imagine. But in the short run, they are often invisible.

One of the reasons we have a hard time recognizing this kind of progress is that, by definition, it is measured in nonevents: the smallpox infection that didnt kill you at age two, the lead paint that didnt give you brain damage, the drinking water that didnt poison you with cholera. We dont tend to think about these kinds of things for a good reason: they didnt happen! But they might well have happened if you or I had been born just two centuries ago, even in the wealthiest countries in the world.

Think about it this way: We build monuments and pay tribute to the lives lost in wars or great tragedies, and that makes sense. But we dont have a habit of building monuments that celebrate deaths that didnt happen, monuments to all the lives saved. Maybe its time we did.

In a sense, human beings have been increasingly protected by an invisible shield, one that has been built, piece by piece, over the last few centuries, keeping us ever safer and further from death. It protects us through countless interventions, big and small: the chlorine in our drinking water, the vaccinations that rid the world of smallpox, the data centers mapping disease outbreaks all around the planet.

A crisis like the global pandemic that began in 2020 gives us a new perspective on all that progress. Pandemics have an interesting tendency to make that invisible shield suddenly and briefly visible. For once, were reminded of how dependent everyday life is on medical science, hospitals, public health authorities, drug supply chains, and more. And an event like the COVID-19 crisis does something else as well: it helps us perceive the holes in that shield, the vulnerabilities, the places where we need new scientific breakthroughs, new systems, new ways of protecting ourselves from emergent threats.