THE MINDS PAST

Michael S. Gazzaniga

University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

1998 by The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gazzaniga, Michael S.

The minds past / Michael S. Gazzaniga.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-520-90025-1

1. Neuropsychology. 2. Brain Evolution. 3. Memory. 4. Developmental neurobiology. I. Title.

QP360.G392 1998

612.892 dc21 97-32505

CIP

Credits are contained in the , which constitutes a continuation of the copyright page.

To the memory of

Charlotte Ramsey Smylie,

a great Texan, a great lady,

and a great friend

As long as the brain is a mystery,

the universe will also be a mystery.

SANTIAGO RAMN Y CAJAL

PREFACE

Over a hundred years ago William James lamented, I wished by treating Psychology like a natural science, to help her to become one. Well, it never occurred. Psychology, which for many was the study of mental life, gave way during the past century to other disciplines. Today the mind sciences are the province of evolutionary biologists, cognitive scientists, neuroscientists, psychophysicists, linguists, computer scientists you name it. This book is about special truths that these new practitioners of the study of mind have unearthed.

Psychology itself is dead. Or, to put it another way, psychology is in a funny situation. My college, Dartmouth, is constructing a magnificent new building for psychology. Yet its four stories go like this: The basement is all neuroscience. The first floor is devoted to classrooms and administration. The second floor houses social psychology, the third floor, cognitive science, and the fourth, cognitive neuroscience. Why is it called the psychology building?

Traditions are long lasting and hard to give up. The odd thing is that everyone but its practitioners knows about the death of psychology. A dean asked the development office why money could not be raised to reimburse the college for the new psychology building. Oh, the alumni think its a dead topic, you know, sort of just counseling. If those guys would call themselves the Department of Brain and Cognitive Science, I could raise $25 million in a week.

The grand questions originally asked by those trained in classical psychology have evolved into matters other scientists can address. My dear friend the late Stanley Schachter of Columbia University told me just before his death that his beloved field of social psychology was not, after all, a cumulative science. Yes, scientists keep asking questions and using the scientific method to answer them, but the answers dont point to a body of knowledge where one result leads to another. It was a strong statement one that he would be the first to qualify. But he was on to something. The field of psychology is not the field of molecular biology, where new discoveries building on old ones are made every day.

This is not to say that psychological processes and psychological states are uninteresting, even boring, subjects. On the contrary, they are fascinating pieces of the mysterious unknown that many curious minds struggle to understand. How the brain enables mind is the question to be answered in the twenty-first century no doubt about it. The next question is how to think about this question. That is the business of this little book. I think the message here is significant, one important enough to be held up for examination if it is to take hold.

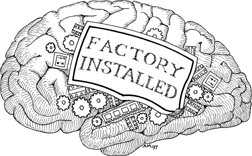

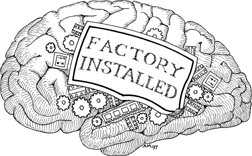

My view of how the brain works is rooted in an evolutionary perspective that moves from the fact that our mental life reflects the actions of many, perhaps dozens to thousands, of neural devices that are built into our brains at the factory. These devices do crucial things for us, from managing our walking and breathing to helping us with syllogisms. There are all kinds and shapes of neural devices, and they are all clever.

At first it is hard to believe that most of these devices do their jobs before we are aware of their actions. We human beings have a centric view of the world. We think our personal selves are directing the show most of the time. I argue that recent research shows this is not true but simply appears to be true because of a special device in our left brain called the interpreter . This one device creates the illusion that we are in charge of our actions, and it does so by interpreting our past the prior actions of our nervous system. If you want to see how I get there, get from factory-built brain to the serene sense of conscious unity we all possess, you will have to read this mercifully short book.

There are many people to thank, not least of whom is the cleaning lady at the Hotel des Grandes Hommes in Paris. Paris is a wonderful place to launch a book. It feeds you and nourishes you and smiles at you while you struggle away in your small room overlooking a small courtyard. The cleaning lady quickly deduced my assignment and carefully plucked her way around the suitcase of science papers, computers, and espresso cups. Always with a smile, she cheered me on until my wife and children arrived; then, as if handing over a baton in a relay race, she announced to my wife, Do you know, this is the first time I have seen him smile in days. So many people keep us going.

Of course, scientific guidance has come from many. Steven Pinker once again read and critiqued the whole effort and provided insight upon insight. He is a remarkable scientist and scholar. Michael Posner did the same, and his usual candor and incisive wit straightened me out on several points. To George Wolford, Leo Chalupa, Michael Miller, Ken Britten, Jeffrey Hutsler, Miquel Marin-Padilla, Charlotte Smylie, and many others I offer many thanks. Finally, I benefited from several lectures over the years, not the least of which came from Robert J. Almo, who is not only an orthopedic surgeon, but also an expert on magic.

Alex Meredith, Ph.D., has once again captured the spirit of our work. Many thanks for his brain art in Chapter 5 and chapter openings. They are perfect.

Most important, I thank Howard Boyer at the University of California Press. Now, this is an editor. He not only cleans up the prose, corrects the sentences, clarifies meaning, and encourages one all the way, he is also smart and savvy, sassy and witty. The book would have been much less without him. And, just when you think you are done, along comes the U.C. Press copy editor. She, too, has contributed much to this book; my profound thanks to Sylvia Stein Wright.

Finally, I am reminded of a crack by Pasko Rakic at Yale University. Rakic, one of the worlds leading neuroscientists, studies how our cortex develops a difficult and challenging problem, to say the least. Every sensible scientist stands in nervous awe of the enormity of such task. In reflecting on this, Rakic quipped, Better not to understand something complex than something simple. My sentiment exactly. Good reading.

MICHAEL S. GAZZANIGA

Sharon, Vermont

THE FICTIONAL SELF

There is no life that can be recaptured wholly, as it was. Which is to say that all biography is ultimately fiction. What does that tell you about the nature of life, and does one really want to know?

BERNARD MALAMUD, Dubins Lives

W ell, we do know about the fiction of our lives and we should want to know. Thats why I have written this book about how our mind and brain accomplish the amazing feat of constructing our past and, in so doing, create the illusion of self, which in turn motivates us to reach beyond our automatic brain.

Next page