For Tyler

Text copyright 2019 by Chronicle Books LLC.

Photography copyright 2019 by the individual photographers.

is a continuation of the copyright page.

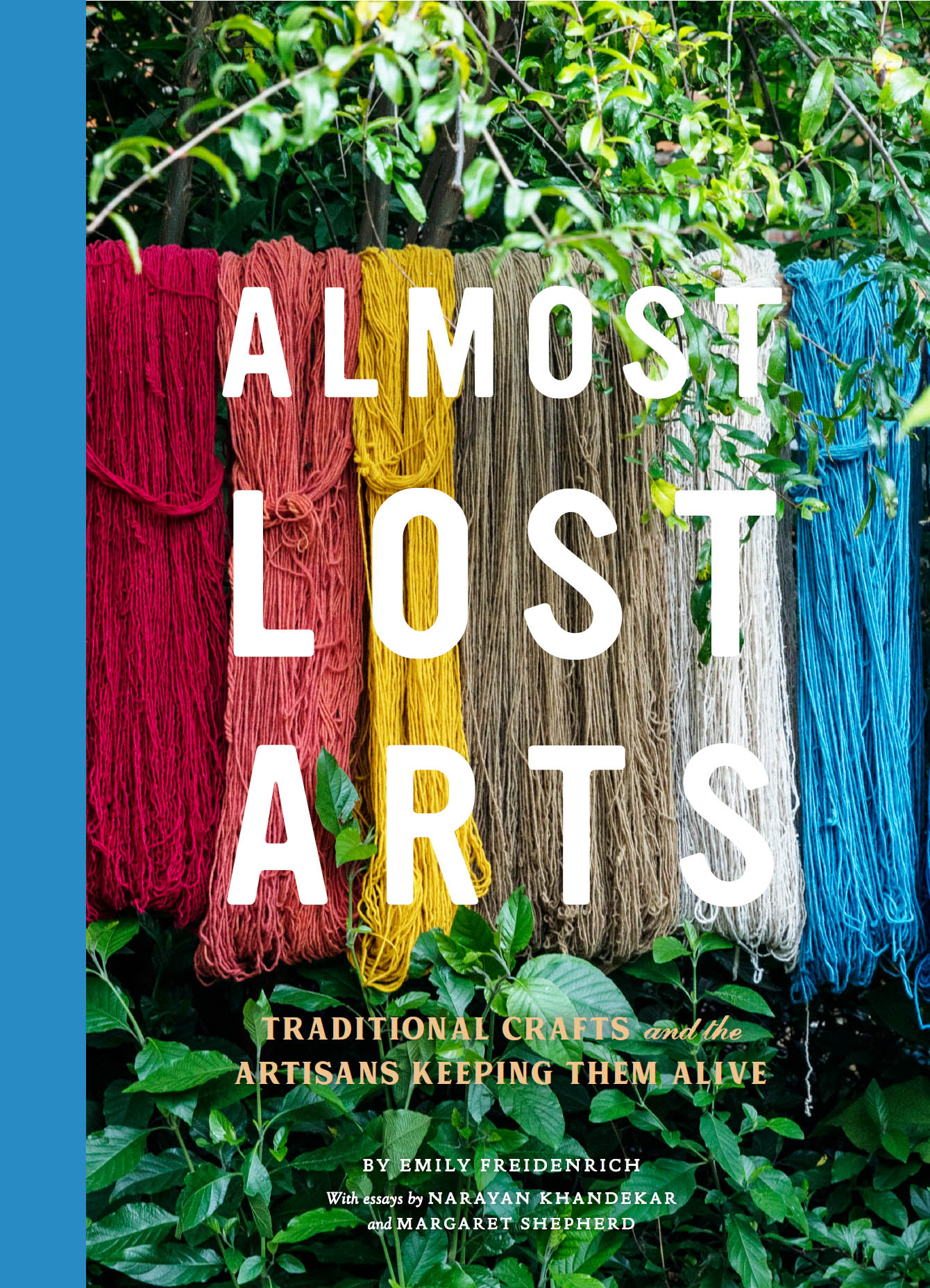

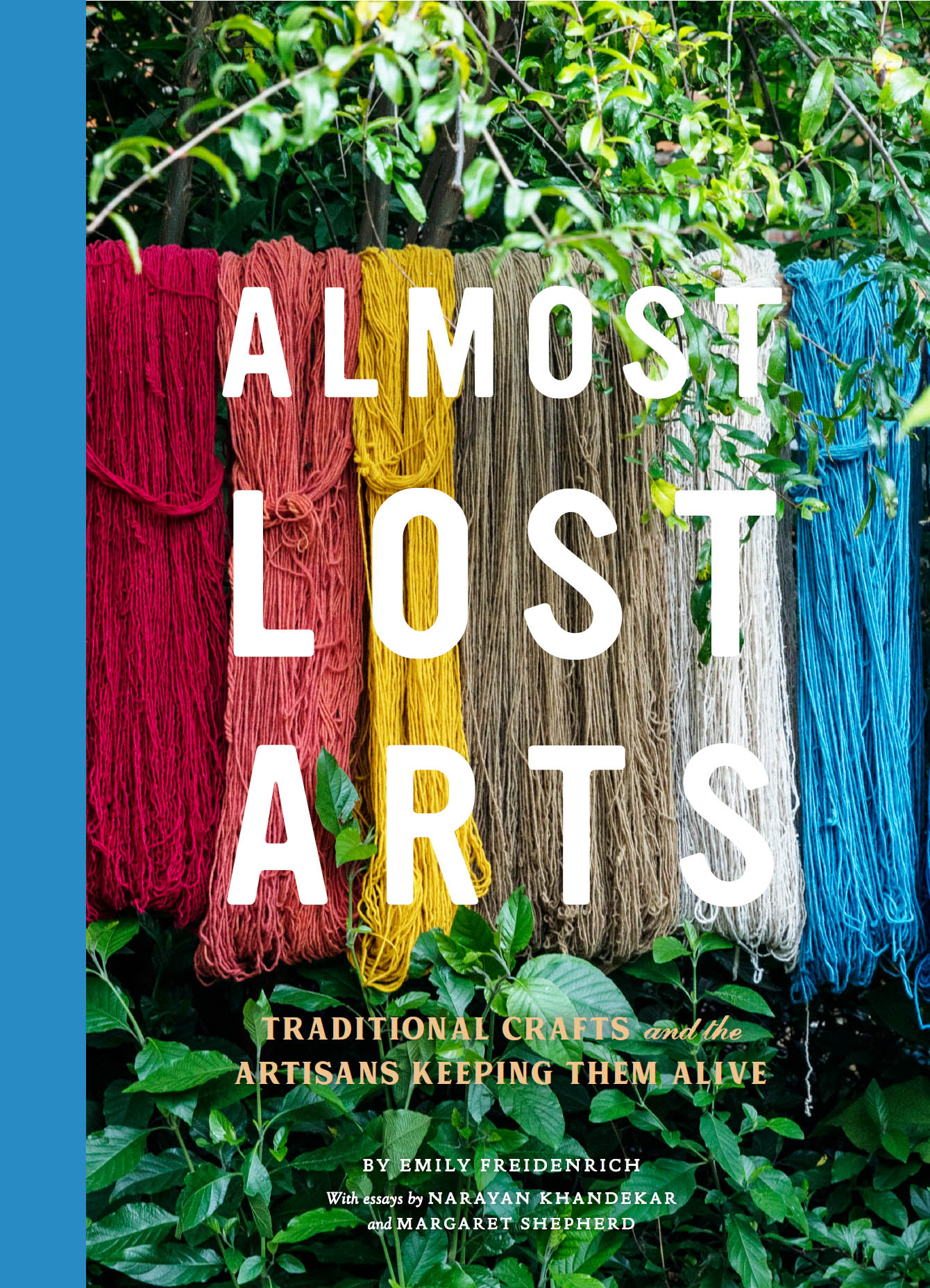

Cover image by Adriana Zehbraukas/ The New York Times /Redux

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 9781452170244 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Freidenrich, Emily, author. | Khandekar, Narayan, 1964- | Shepherd, Margaret.

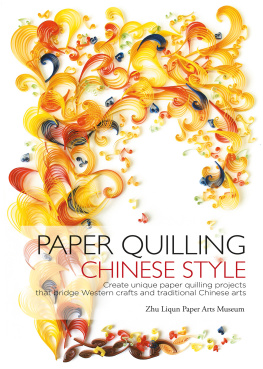

Title: Almost lost arts : traditional crafts and the artisans keeping them alive / by Emily Freidenrich ; with essays by Narayan Khandekar and Margaret Shepherd.

Description: San Francisco, California : Chronicle Books LLC, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018039987 | ISBN 9781452170206 (alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Handicraft. | Industrial arts. | Artisans.

Classification: LCC TT145 .F74 2019 | DDC 745.5dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018039987

Design by Kayla Ferriera.

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

The Meaning of Making

GETTING OUT THERE AND DOING THINGS WITH YOUR HANDS IS HONEST AND HUMAN. Photographer Ray Bidegain is talking about what drives his work in alternative process and wet plate photography, but his words largely reflect the feelings of the other artists, artisans, and makers interviewed in this book. From traditional adobe-builders to an antiquarian horologist, from sign painters to bronze casters, all of them work with their hands. Almost Lost Arts celebrates these few skilled artists and devoted artisans dedicated to creating something tangible, or useful, or beautiful, every day.

Whether they are continuing or reviving a craft that is decades or even centuries old, every maker is inseparable from their process. And it is the presence of the human hand in the end resulta ceramic bowl, or weaving, or photograph, or paintingthat cannot be replicated in a commercial setting. There is purity and honesty in the uncanny perfection that comes with time and experience and skill and love, and equally so in the moments of imperfection that remind us of the maker behind the object.

You may have sensed this. Maybe you once made something that felt as though it captured a part of you. Perhaps youve experienced awe while looking at the uncannily smooth brush strokes of a painting, or admired the skill (earned from a lifetime of dedication) in a piece of furniture. Art critic Walter Benjamin called this effect the aura of an original work of artan awareness in the onlooker of something living that feels almost physical; a sense of the objects history, and of the emotion, skill, and human hand behind it.

In many cases, that history is deeply important. Several artisans in this book follow traditional techniques to keep alive cultural heritage and celebrate national identity. Indigenous Zapotec weaver Porfirio Gutirrez and his family are among the few weavers in their Oaxacan village who follow the ancient recipes for natural dyes (using native plant materials) for their vibrant textiles and weavings. Its an art at the edge of disappearing, as synthetic dyes appeal to many weavers by saving time and offering a wider range of colors. But, according to Gutirrez, they are often toxic and are costing his culture an ancestral tradition that goes back to pre-Columbian times.

Thousands of miles away in Tokyo, the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Printing is dedicated to maintaining the art of the Ukiyo-e print. Its atelier of talented carvers, printers, and publishers collaborate with artists around the world to produce these traditional prints. Meanwhile in Kyoto, lacquer artist Muneaki Shimode carefully repairs broken ceramic vessels with urushi lacquer and gold powder in the stunning Kintsugi technique. Both arts are important representations of Japanese aesthetics, cultural history, and philosophical ideals, but every year, fewer masters are certified in the practices.

Following tradition can also lead organically to innovation, experimentation, and growth. Korean potter Lee Eun Bum, who specializes in the ancient Goryeo celadon tradition, works under the motto of mastering the old to create new. He explains: I always contemplate on how I should approach a traditional technique into my work, how it can be efficient while being useful. Contemporary artist Daniel Arshams innovations in casting processes continue to push the medium to new places, using unconventional media like volcanic ash to cast everyday objects like Chicago Bulls jackets and Pentax cameras.

But for many Old-World techniques displaced by technology over time, innovation comes not just by choice, but by necessity. Since knowledge was once passed from master to apprentice by demonstration and oral history, there are gaps in that knowledge today. When he began making globes as a hobby, Londoner Peter Bellerby spent two years learning his craft through experimentation and failure before he produced the two perfect globes hed set out to make, and had developed a process he could be satisfied with (at least as a start). In Two Rivers, Wisconsin, Hamilton Wood Type & Printing Museum director Jim Moran describes printing machines and aspects of the wood moveable type process that were simply never recorded. The museum is dedicated to uncovering those secrets through the same patient acts of trial and error.

But these challenges are part of the magic and the meaning behind the making. And with time, these arts have been revived, or have managed to survive the threat of obsolescence. The craftspeople youll meet in this book are just a small handful of the makers in our communities and cities all over the world who work every day to carry their cultural history into the future, who dedicate their lives to their work for love of artistry, and who keep alive knowledge that otherwise would be lost.

The Globemakers

I never was formally schooled in the arts, says Bellerby. Many of the greatest makers I know have simply been the type of people who are creative in their free time from a young age. Bellerby has always worked with his hands and was a violin maker and a house restorer before taking up his current profession. These two trades, he says, gave him an understanding of many of the tools and techniques used in globemaking.

Next page