Draw it with

your eyes closed:

the art of the

art assignment

EDITED BY

PAPER MONUMENT

PAM LINS

HEATHER HART

Take an 18 24 inch piece of paper and make a drawing using nothing but your car.

CARRIE MOYER

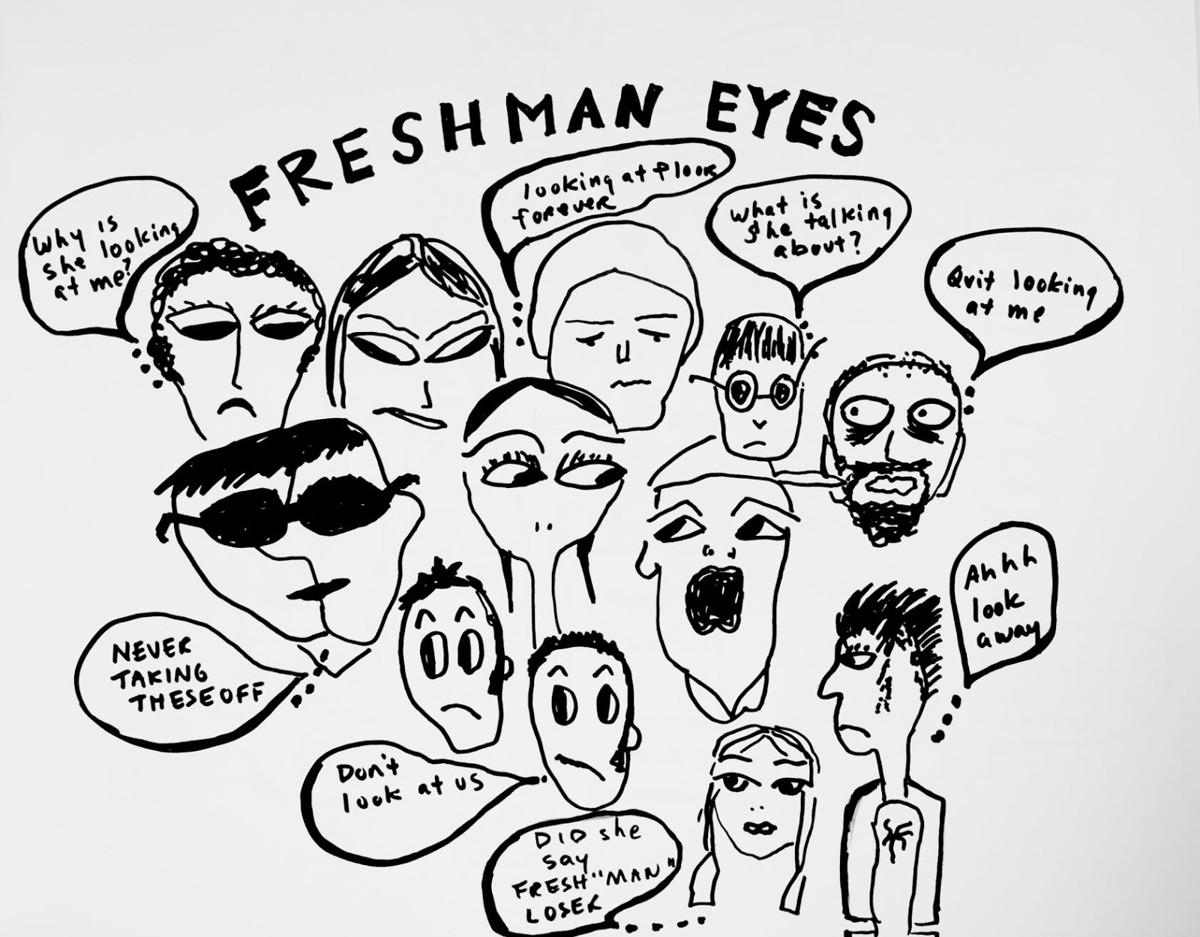

In my freshman year at Bennington College, I took a set design class with Tony Carruthers: a mad, charismatic Scotsman, multimedia artist, and legendary teacher. He asked us to design a set based on L. Ron Hubbards Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Heath . Tony had a brilliant way of cajoling us to open up our little high-school brains (Who cares about the fucking actors? Theyre just props!) and embrace the absurdity of the task at hand. My maquette was negligiblea red-hot volcano surrounded by a ring of jutting cardboard and tin foil flats (think Metropolis )but the experience of studying with a larger-than-life true believer was indelible. I wasnt stuck in Oregon anymore. This was what REAL ART felt like.

OLIVER WASOW

As I see it, there are three ways to approach teaching art.

1. The Cheerleader

For better or worse (OK, worse) this is the model I most adhere to.

Im from the if you dont have anything nice to say, dont say it school. It serves no ones needs but I cant help it. Codepenents make the worst teachers.

A good teacher probably needs to believe that one thing is better than another, but I have difficulty with the idea of objective differences in quality. My critique sessions tend to resemble confidence-building exercises. Oprah giving hugs. You go, girl!

I make a better cheerleader than coach.

2. The Role Model

This one I dont do. I couldnt, even if I tried. It comes from reading too many famous artist biographies. Its nurtured by bitter old faculty members who would rather be in their studios working, and it inevitably leads to creepy teachers sleeping with students. Really, it does no one any good at all.

3. The Dialogue Facilitator

This is probably the best way to approach teaching art, and if I can shut up long enough Im not so bad at it. On a good day, Im fairly adept at fostering dialogue and getting students to talk. I can go on at great length, citing points of reference, texts to read, and artists to look at. I can dissect the meaning of a work of art from any number of perspectives. Freud, Marx, even the French GuysI can cite them all and bring multiple meanings to the slightest mark or material. And sometimes, just sometimes, I can even believe what Im saying.

Of course all of this is made much easier if Im teaching in a room with a projector and a high-speed Internet connection. Theres really no reference that cant be made more interesting or conversation enhanced with a good Google search. Sure, this can result in a good hour of class time being spent watching kittens play piano, but really, is that so wrong?

GEORGE RUSH

In my experience, assignments are sort of like folk songs, or certain kinds of jokes. Theyre retold and adapted from generation to generation of teachers, tinkered with, misheard, brought up to date. Even when I think Ive come up with something new, it always ends up being a version of something else.

In comedyas opposed to casual joke-tellingthere are various mechanisms in place to deal with the issue of stolen jokes. Was a joke stolen outright, inappropriately adapted, or merely the coincidence of thematic overlap? One can imagine a jury of comics sitting in a dark club, parsing the language of a joke and determining whether or not an infraction had been committed. When Robin Williams, an infamous pilferer of other comedians material, was called out, he would just pay off the offended comic. The popular and unfunny Dane Cook famously accused another comic of stealing his essence. And though we may imagine certain artists and art professors making the same claim, in teaching art there are no expectations of intellectual property rights. If there were, how would these be enforced?

I often teach beginning drawing and a favorite assignment is ostensibly from the Bauhaus, though Ive looked and never found it published in any of the books about the school. Maybe it was passed through Josef Albers to the Yale crowd of the 1960s and 70s. The painter Peter Charlap passed it to me and I havent changed it a bit. In any event, it never fails and I often use it to start the semester. It immediately teaches the students something about change, time, erasure, composition, and drawing as an event. And the drawings produced by the students are beautiful, which always helps morale. There are two versions:

Erasure with Line

( Read out loud to class, waiting for students to complete each step before going on to the next one. )

Im going to give you a set of instructions to follow.

These instructions are intentionally cryptic.

You cant ask any questions.

You must reason your way through the problem.

Using line only, draw one simple geometric shape, such as a square, triangle or circle.

Without overlapping or intersecting, draw a different shape.

Now, draw another. Choose your favorite.

Make the other 2 like your favorite.

Enlarge one of the shapes.

Reduce one of them.

Make one shape touch one edge of the page.

Make the other two touch two different sides.

Without moving the shapes from the sides, make each touch the other two.

Introduce a new shape thats different.

Keeping the original 3 shapes in the same places, make them like the new shape.

Make one shape larger than all the others.

Make one 50% smaller than the largest shape.

Make one of the 2 remaining shapes touch 2 sides of the page.

Discuss.

Erasure with Tone

Use 18 24 inch paper and vine charcoal.

On a new sheet of paper and using no line,

draw a white circle.

On the same sheet, and using no line,

draw a black circle.

Draw a gray circle.

Move one circle so that it is touching the edge

of the page.

Make one circle 50% larger than all the others.

Add another shape of your choice, any value.

Take a new sheet of paper.

Copy the negative shapes only.

Fold the sheet into 4 quadrants.

Make the shapes different values.

Repeat one quadrant into another.

Discuss.

PATRICIA TREIB

The first art assignment I ever received, on my first day at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, in 1997, was the most humbling and powerful one Ive ever experienced. After introducing our 2-D Foundations class to the work of Giorgio Morandi by way of a full color monograph, Matthew Girson instructed us to pick up an assortment of generic bottles, vessels, and brushesbut no paint or surfacesand led us on a walk out of the classroom into the morning heat. Upon arriving at a stretch of newly made asphalt near Buckingham Fountain, we were asked to set up a Morandiesque arrangement using the bottles. Girson told us to paint what we saw onto the absorbent surface of the black asphalt, using our brushes and water from a drinking fountain. This was surprisingly effective. Using these austere means, we were able to make recognizable, nuanced images. We became conscious of the sun as an integral element in the existence of the image: it would never sit still, because it was evaporating before our eyes. We had to detach from the object, having no means to preserve our labor. What could have been a mere novelty became something else when we were instructed to continue our paintings for the rest of class: five more hours. Even though we ended the day empty-handed, I felt energized by the beauty of an immaterial experience.

MOLLY SMITH

FIRST SCULPTURE ASSIGNMENT

Next page