Gardening with Shape, Line and Texture

Gardening with Shape, Line and Texture

A Plant Design Sourcebook

Linden Hawthorne

For Freya and Ellen, Richard and Virginia

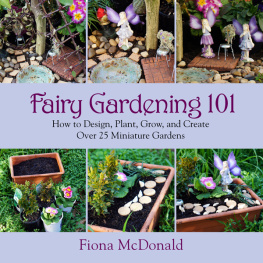

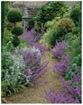

Front cover

The complementary shapes, lines and textures of

verbascums, eremuruses, poppies and alliums contribute

to the success of Beth Chattos Gravel Garden in Essex,

England. Photo by Andrew Lawson

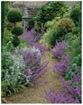

Frontispiece

The restored woodland and water garden designed by

Harold Peto exploits a device that Pope and Kent would

have known as calling in the countryborrowing

the wider landscape as a focal point. (Wayford Manor,

Crewkerne, Somerset) Photo by Nicola Stocken Tomkins

Text copyright Linden Hawthorne. All rights reserved.

Photographs copyright Jonathan Buckley, Torie Chugg, Liz

Eddison, Sam Eddison, Derek Harris, Linden Hawthorne,

Andrew Lawson, Marie OHara, Gary Rogers, Jane Sebire,

Derek St Romaine, Nicola Stocken Tomkins and Mark Taylor.

Illustrations copyright Catriona Stewart. Credits appear on

page 280.

Published in 2009 by Timber Press, Inc.

The Haseltine Building

133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450

Portland, Oregon 97204-3527

www.timberpress.com

2 The Quadrant

135 Salusbury Road

London NW6 6RJ

www.timberpress.co.uk

Design by Dick Malt

Printed in China

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hawthorne, Linden.

Gardening with shape, line and texture : a plant design

sourcebook / Linden Hawthorne. --1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-88192-888-4

1. Gardens--Design. 2. Landscape gardening. 3. Landscape

plants. I. Title.

SB472.45.H388 2009

712.6--dc22

2009022652

A catalogue record for this book is also available from the British Library.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to Erica Gordon-Mallin and Anna Mumford at Timber Press, for faith and patience, and for acquiring the services of the fabulous photographers at the Garden Collection: Andrew Lawson, Derek Harris, Derek St Romaine, Gary Rogers, Jane Sebire, Jonathan Buckley, Liz Eddison, Marie OHara, Nicola Stocken Tomkins, Sam Eddison, Mark Taylor and Torie Chugg. Special thanks also to Catriona Stewart.

Preface

As gardeners we take enormous pleasure in simply strolling through the garden, head down, enjoying the individual beauties of plants. Yet when we sit back to view the combined effectthe whole planting, the whole gardenwe sometimes feel that something is missing: something more is needed if the garden is to be a finer thing than just a plant collection.

Many of us want to create a garden that is truly our own work of art. This book is for the garden-maker whose ambitions extend beyond copying anothers style; however elegant and covetable the original, that approach leads to pastiche, and never gives the satisfaction of a work with its creators own stamp.

In my experience, it is exactly when we do treat a garden as a work of art that we create the most beautiful and unique of plant compositions. To this end, we can benefit from learning a pattern languagea basic design vocabulary that, once grasped, allows us to confidently express our taste with style.

In the first chapter, I describe principles common to other art forms, such as architecture, painting, photography, graphic art and all sorts of design, and I suggest how to apply them in gardens. Grouping plants according to their shape and line is central to my approach, and the plant directories in the chapters that follow are organized this way. The focus will be on their shape, line, texture and formand how they can be used to best effect in your plant compositions.

As with all systems of classification, there are always things that dont fall neatly into line. This is not a book about painting by numbersit is about painting with plants. The groups outlined in this books plant directories are a simple aid to placing plants in a composition. Any plant that you grow or buy can be ascribed loosely to one of these categories, which allows you to place it well rather than cramming it in.

Aesthetic elements alone, though, are not the complete picture in good garden design. All good designin any fielddemands that structural and functional elements are integrated to meet the practical needs of the user to the best aesthetic advantage: in other words, utility with beauty. And although human needs are paramount in the garden, it is essential to consider other living materials, the plants, among the intended users of the space. If their needs are not met, they do not thrive, and your palette is compromised, which is not ultimately conducive to gardening joy.

Good garden design is never simply a visual art, but a craft that marries the earthy practical skills of the gardener with the eye of an artist, and there are many similarities, I think, in the desires and imaginations of both. After all, if gardening didnt engage heart, soul and brain, it would just be so much hard labour.

Clipped balls of box, holly and privet and mirrored plantings of Phlomis, Nepeta and Stachys echoed by the upswept branches of Mahonia lend unity and a strong underlying rhythm.

Painting with Plants

The idea that one can create a garden or landscape in much the same way as an artist composes a picture is by no means new. Many of the great garden designers including William Kent, Gertrude Jekyll, Russell Page, Roberto Burle Marx and Thomas Church were trained in visual arts, and the principles of good composition are seen in all of their gardens, whether traditional or modern.

The principles were consciously expressed in the eighteenth-century English landscape. During his Grand Tour of Italy in the early eighteenth century, William Kent, architect, painter and progenitor of the English Landscape style, studied architecture and became familiar with the work of the Landscape painters Claude Lorrain, Nicolas Poussin and Salvator Rosa. His friend, the poet Alexander Pope, commended the principle that you paints as you plant and coined the dictum that all gardening is landscape paintinga maxim that Kent made his own. Kents landscape work, in which he created three-dimensional pictures from a palette of woods, lawn, water and the contrasts of light and shade, has been described as that of a purely visual artist, rather than the work of a gardener. Put crudely, with this pictorial sensibility he placed garden buildings in an idealized landscape, drawing inspiration from...

Next page