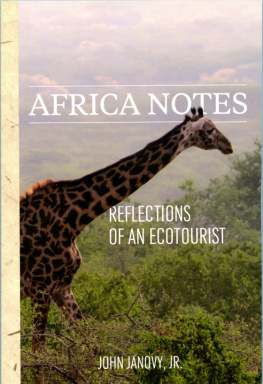

AFRICA NOTES

Reflections of anEcotourist

John Janovy, Jr.

SmashwordsEdition

Copyright Center for Great Plains Studies,2018

Except for brief quotes used in reviews, nopart of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,or transmitted in any form by any means, including mechanical,electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without priorwritten permission of the copyright holder. NOTE: This e-book isbeing published exclusively by John Janovy, Jr., with writtenpermission and endorsement from the copyright holder, theUniversity of Nebraska Center for Great Plains Studies. The Centeris a non-profit organization that promotes teaching, research, andoutreach on subjects pertaining to the North American Great Plains,a region of enormous economic and social importance to the UnitedStates and Canada. Tax-deductible donations can be sent to theCenter at 306 Hewitt Place, 1155 Q Street, Lincoln, NE68588-0214

Paperback copies of Africa Notes may beordered from Nebraska Marketplace for $20 plus shipping andhandling; the web site is https://marketplace.unl.edu/liedcenter/africa-notes-reflections-of-an-acotourist-mp-124.html

Cover design by Alexa Horn.

ISBN: 978-0-9863887-3-6

*******

CONTENTS

*******

AN INTRODUCTION

We all have travel experiences, many ofwhich are, in my view, challenging. Nevertheless, we save up money,buy tickets to far-off lands, and walk, fully aware of what we aredoing, into metal tubes in which we will be sealed then taken sixor seven miles into the air, through hurricane-force winds, to anenormous building where well have to run a mile or two whilecarrying thirty pounds of stuff if we dont want to spend the nightwatching sparrows come down out of the I-beam rafters to pick uppopcorn dropped by fellow adventurers. Furthermore, we routinelyexhibit this behavior for what some might think are the most flimsyof reasons, for example, going to Africa after dreaming about itfrom the time we were in the fourth grade.

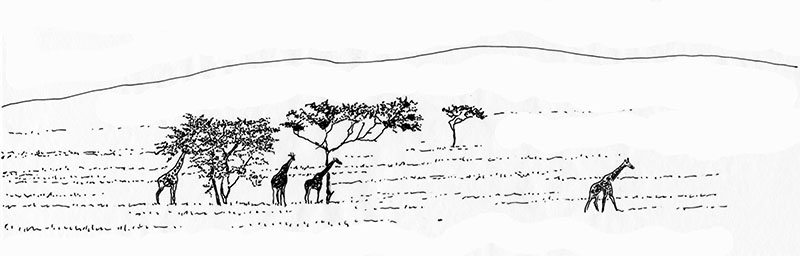

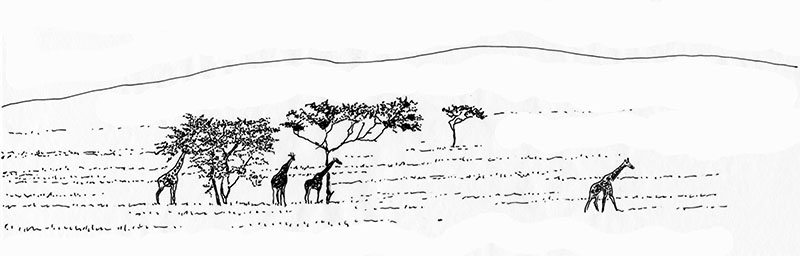

For decades prior to our Botswana andTanzania adventures, I was told by professional colleagues to seeAfrica before its gone. When my wife, Karen, and I finally madethose trips, we were simply stunned by the incredible beauty ofeverything animals, plants, habitats, and people. I took thousandsof digital photographs; none of those images can even begin toconvey what an impala herd looks like in the bush. My kudu picturesare great, but they cant come close to telling you what a kududoes to your mind the first time you see one in the wild. Mywildebeest photographs are amazing; their main function is to bringback the memory of taking them. With my background as a biologist,half a century of doing research on animal parasites, and teachingzoology courses to thousands, this travel taught me how ignorant Ireally was of all those species Id seen only in zoos.

Karen printed her hundreds of photographs,labeled them, and put them into two large albums. Watching her faceas she goes through those albums makes me realize that she also hasthat lingering, nagging desire to go back. Our encounters withAfrica, even knowing how managed they were, and how stereotypicalin many ways, produced changes in us that we simply cannotdescribe. I honestly believe those changes now strongly affect ourviews of the natural world, of human diversity, of geological andevolutionary history, of language, of politics, and of culture ingeneral. This book is my attempt to explain those changes, how theycame about, and especially how they are now integrated into ourmemories, past experiences, and perceptions of current events.

Of course, there exists a staggering amountof literature on the African continent, from which anyone withaccess to a library or the internet could easily become partiallyeducated prior to visiting the Serengeti. But one of our driversdescribed the perceptions of many tourists, especially Americans,by commenting that most people think of Africa as a singlecountry. He made this observation as we were traveling throughtribal lands listening to a radio conversation in Swahili, a Bantulanguage adopted across much of the continent to alleviate theproblem of communicating between cultures and human lineages datingback half a million years and speaking up to three thousanddifferent languages and dialects. The drivers conversation, ofwhich I understood nothing except his comment about averageAmericans perceptions of a continent, evidently concerned asleeping leopard. Once he clicked off, returning the handset to itsplace on his nicely decorated dashboard, he pushed the pedal to themetal. I immediately had two unspoken questions: How quickly dosleeping leopards wake up? And, had he ever thought about enteringhis Toyota Land Cruiser in the Baja 1000?

Among the real surprises awaiting one on atypical tourist safari is the number of tourists. That number isenormous, but not as large as local vendors, lodge staff, andmarket hagglers would like to see arrive in places like Arusha,Tanzania, with a Visa card and a backpack full of crisp, post-2009currency. The other surprise that awaits a person taking advantageof packages offered by companies such as Classic Escapes, theoutfit that put together our trips, is the sophistication of staffand facilities in various game reserves and national parks. Karenand I were in ten different facilities in Botswana and Tanzania,some featuring tents that redefine the term. As a Boy Scout, noneof my World War II vintage pup tents ever had full bathrooms withhot showers. As a traveler making my way down the Baja Californiapeninsula in 1989 and 1990, my tent was quite a bit more elaboratethan the one I had as a Boy Scout, but still featured no indoorplumbing. Nor was I ever greeted with a song and a hot washcloth atany scout camp in Oklahoma or public campground in Mexico, althoughin places like El Rosario the scabby dogs did show up, sniffingaround our backpacks, a welcoming committee of sorts.

Of all my tourist impressions, the sheeraudacity of constructing then maintaining resorts deep in the bushhas to be one of the most powerful. At Duma Tau, in Botswana, wewere given a tour of the facilities, including vehicle maintenanceshop, water purification plant, electrical power plant, bakery, andlaundry. Power was all solar, backed up by battery. The only thingI remember about the water is that in all of our Botswana camps,there was pure, safe water to drink, supplied by the plant, withthe only plastic bottles being souvenirs given to us. We were ableto charge cell phones and cameras. Our local host, finishing thetour, reminded us that our venues were originally hunting camps,but now that they had been converted to tourist lodging and dining;they were ultra-sophisticated green operations that could indeed bedisassembled, totally, and removed. The implication was that avacated site would be reclaimed by mopane trees and elephants, andthat within a very few years nobody would be able to recognize theplace for what it had been.

Only the laundry was sobering. Women washedlinens and guest clothing by hand in large metal sinks, scrubbingin a manner reminiscent of pre-World War II rural Oklahomahouseholds where washboards were actually used, regularly, and notas musical instruments in some folk band. That mental image ofthose women in Botswana standing beside the sinks and scrubbingsurfaced in Tanzania two years later when I sent a pair of pantsNorth Face Paramount Peak II, quintessential tourist gearto bewashed. Id worn them for several days; they had paint spots fromwhen Id worn them a year earlier while remodeling a piece ofrental property. Those paint spots had not come out during half adozen machine washes at home. The spots were gone, however, whenthose same pants returned from a laundry in the African bush.Disappearance of paint spots under such circumstances makes animpression on you and forces you to rethink the power of peopleversus the power of machines.

Next page