Old Fields

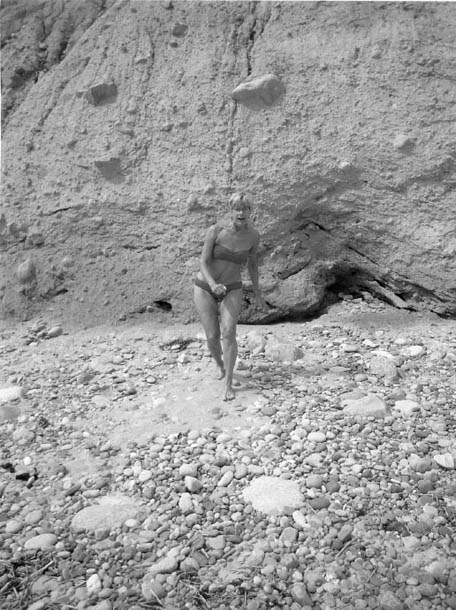

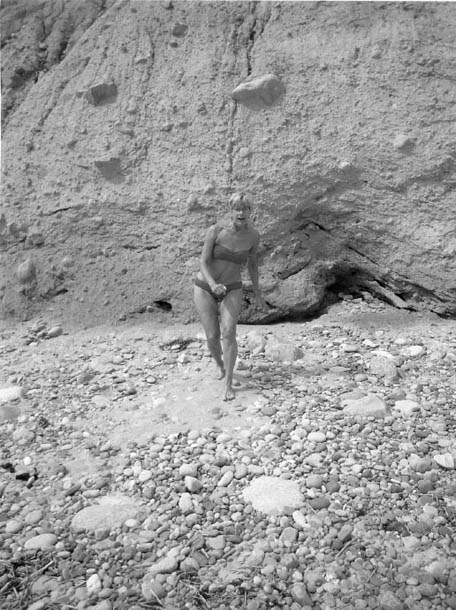

Only rarely do color, light, and form combine to flatten perspective. Here the artist Suzanne Jevne casts almost no shadow, appears to float, and seems to have just thrown the rock embedded in the clay cliff ten feet behind her.

JOHN R. STILGOE

Old Fields

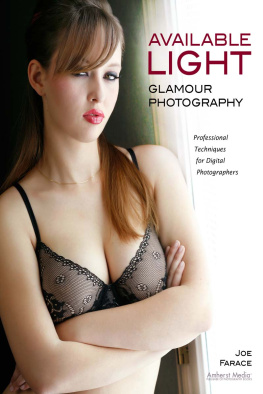

Photography, Glamour,

and Fantasy Landscape

University of Virginia Press

2014 by the Rector and Visitors

of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2014

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stilgoe, John R., 1949.

Old fields : photography, glamour, and fantasy landscape /

John R. Stilgoe.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8139-3515-7 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8139-3516-4 (e-book)

1. PhotographyPhilosophy. 2. Landscape photography.

3. Vernacular photography. 4. Photography, Artistic.

I. Title.

TR183.S755 2014

778.3dc23

2013024097

All illustrations unless otherwise noted from the authors collection. , courtesy Houghton Library, Harvard University.

for Suzanne Jevne

CONTENTS

PREFACE

LANDSCAPE GLIMMERS IN FANTASY FICTION AND IN GLAMOUR PHOTOGraphy. Both subvert contemporary convention and postmodern ideology. They herald the end of traditional ecosystem concern and the imminent arrival of designed life forms, and they offer innovative views of traditional landscape, especially of devalued and abandoned terrain.

They assert that some people, especially some women, are gifted in ways that transform landscape and shatter brittle meritocracies. Fantasy fiction emphasizes unnerving novelty in space and in seeing, and in the magic of visual magic, glamour itself. In the twilight of film photography it appeals to young people and adults no longer adept at deliberate and accidental image making. Glamour photography slithers among photographic genres definitely not art, deftly separating itself from erotica, pornography, fashion imagery, from pinup, cheesecake, and formal portraiture, and from casual and candid picture making of landscape and people. Almost always, its critics focus on its models, not its settings. In the first years of the twenty-first century, glamour photography still embraces barbed definitions of visual magic and disused landscape that suffuse contemporary fantasy fiction written ostensibly for children and teenagers but now read by adults. Together, fantasy fiction and glamour photography inaugurate something glimpsed just around the curve of time.

Glamour itself creates tension. Always the tension allures. It snares the eye, skews the consciousness, and sometimes evokes physical action. It halts walking adults, stills conversation, now and then produces goose bumps, often despite will power marshaled against it. All kissing cousins of the erotic feelings pornography often stimulates, the physical responses suggest that glamour is power only slightly refined from raw energy. Children glimpse it rarely and fleetingly and want to know it intimately, but formal education trains their eyes from it. Anthropologists once wrote of animal magnetism and political commentators still gush over charisma, but schoolteachers and scholars shun glamour and glamour photography especially. Some children descry the organized avoidance and veer toward the power that scares so many self-styled responsible adults.

Visual magicglammyre or glamourwarns discerning people that words and numbers prove less than comprehensive, but only photographers, often idiosyncratic amateurs long estranged from mainstream art but now on the cusp of discovery, routinely embrace it. Fantasy fiction introduces glamour to wider audiences: its preoccupation with faerie, what young scholars define as some place other than the everyday, emphasizes visual acuity. Apparition and appearance order the best of fantasy, especially that written for adolescents. Glamour structures much of J. R. R. Tolkiens 1937 The Hobbit and subsequent books, but in the 1970s it focused fantasy authors already dismissing kinetic media. As most children and adults forsook looking around for gazing at cinema and television screens, fantasy writers followed the lead of a handful of early twentieth-century photographers whose images contradicted cinema views. Later photographers clashed with the makers of Hollywood and television imagery and ideology, then diverged from the main-traveled roads media studies scholars trudge. Art historians ignore the deviants, as do almost everyone else: academics dismiss their work as sexist or worse. Post-1970s fantasy fiction, especially that directed at very smart adolescents in well-nigh subversive ways, dismisses ordinary landscape and visual media. It maps a scarcely discernible path away from mere consumption of images, a faint, overgrown path meandering into the ruins and lone-lands of glamour photography. It populates new landscape with new genii loci in ways glamour photographers approve.

Glamour is power its makers scarcely control. Visually produced magic frightens the timid: they condemn it as delusive or compulsively alluring. Women and photographers who wield its power understand its relation to place and to an elitist acuity that grows stronger by the year. They know that genuine glamour originates often in accident, frequently slips free of stricture, and sometimes harms. The timid fear glamour, but they fear more the ways it empowers children bored with school and mass media alike.

Modern fantasy fiction recognizes glamour as elucidating secularization and worries about planetary climate transformation, social realignment, and the imminence and potential preeminence of biological engineering. It prepares readers for inchoate change heralded by visual force. It warns of danger, difference, and opportunity, while savoring all; it champions hard looking, seeing shadows of transparent or invisible things and forces. It gradually replaces the photography that establishment critics still dismiss as illustration enterprise neither art nor advertising. Indeed, except among cognoscenti it supplants almost all but cell-phone snapshot photography. Despite the proliferation of digital cameras and camera-fitted cell phones, few young people know much about photographic technique, and almost none know glamour photography. Many women equate it with pornography and scorn it or pretend to scorn it even as they feel its allure. Many men know it as something distinct from pornography but rarely mentioned aloud since the middle 1970s. Nowadays they accept it as power imbued with chance, an emblem of imminent change fitfully traced in the best fantasy fiction.

A camera can make anyone, even a child or other novice, momentarily a gifted photographer. While pencils, paints, and paper cannot make a neophyte a superb artist any more than a saxophone or violin can make their holders instantly musicians, it is possible for a first-time photographer to make a superb image. It is possible, if unlikely, because it is technically feasible.

What cameras do independently makes meditative photographers wary. Photographers often forget the mischief latent in cameras, but a few know the intermittent, sometimes intransigent independence of their instruments. So long as he clicks away thoughtlessly, or with only a little regard for exposure and composition, the typical image maker almost never discovers surprise. Only when he begins making better than average images in other than average light and surroundings may he encounter excellence by chance. Glamour thrives in traditional photography now alien to an electronics-addicted, image-consuming generation. It suffuses quality fantasy fiction because glamour is raw, often erratic visual power a few photographers understood by 1925 but which disappeared from Hollywood film soon after. But ten years later, 35 mm photography, itself a product of the Hollywood industry using 35 mm cine film, almost obliterated a photographic effort mainstream critics by then derided. Only a few photographers persevered. Their success shaped a new genre of edgy fiction emphasizing special people making abandoned or unfrequented landscape special.

Next page