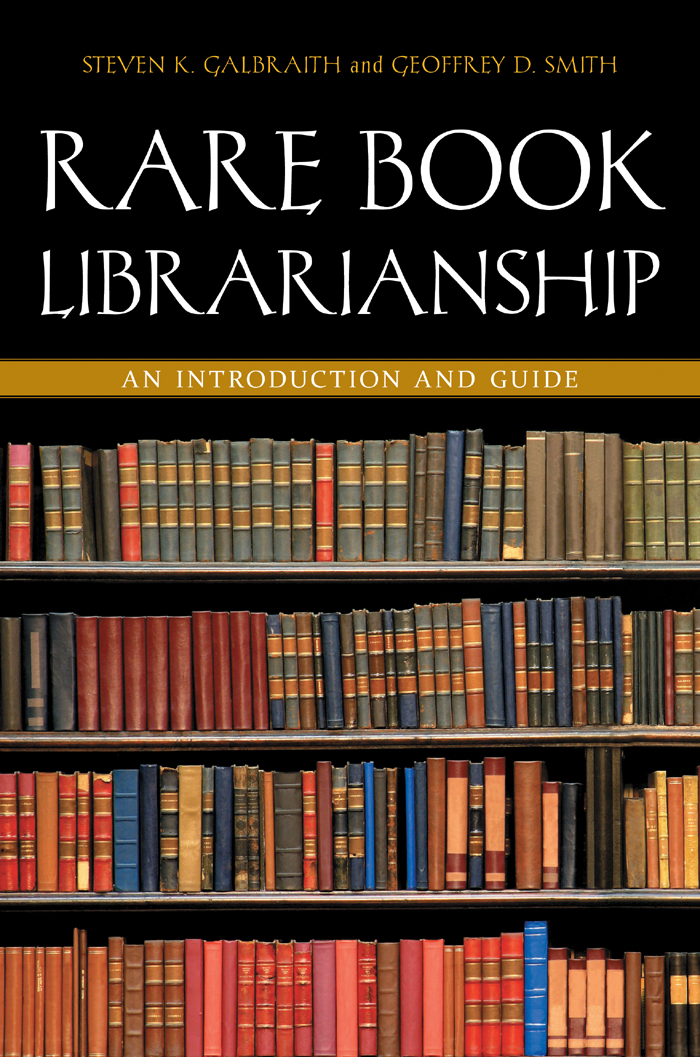

STEVEN K. GALBRAITH is Curator of the Cary Graphic Arts Collection at Rochester Institute of Technology. He has a Ph.D. in English Literature from The Ohio State University and an M.L.S. from the University at Buffalo. Prior to coming to RIT, he was the Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Books at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, the Curator of Early Modern Books and Manuscripts at The Ohio State University, and a reference librarian at the University of Maine. He is the author of The Undergraduates Companion to English Renaissance Writers and Their Web Sites and has served as general editor of the Undergraduates Companion Series and the Author Research Series for Libraries Unlimited. He has written articles and reports on early English printing, book conservation and digitization, and the poet Edmund Spenser.

GEOFFREY D. SMITH is the Head of the Rare Books and Manuscripts Library at The Ohio State University. He holds a PhD in American Literature and Textual Studies from Indiana University. He is the author of American Fiction, 19011925: A Bibliography (1997), and is general editor for a series of textual editions of William S. Burroughs under The Ohio State University Press. The first volume of the Burroughs series, Everything Lost: The Latin American Notebooks of William S. Burroughs, was published in December 2007. He has written critical articles on Henry James, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and William Dean Howells, in addition to numerous publications on rare book and textual studies topics.

Rare Book Librarianship

An Introduction and Guide

Steven K. Galbraith and Geoffrey D. Smith

ABC-CLIO, LLC

Copyright 2012 by ABC-CLIO, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a

review, or reproducibles, which may be copied for classroom and educational programs

only, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Galbraith, Steven Kenneth.

Rare book librarianship : an introduction and guide / Steven K. Galbraith and Geoffrey D. Smith.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9781591588818 (pbk.) ISBN 9781591588825 (e-book)

1. Rare book librarianship. 2. LibrariesSpecial collectionsRare books. 3. Rare booksBibliographyMethodology. 4. Rare book librariesAdministration. I. Smith, Geoffrey D. (Geoffrey Dayton), 1948 II. Title.

Z688.R3G35 2012

025.19609dc23 2012012354

ISBN: 9781591588818

EISBN: 9781591588825

1615141312 12345

This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook.

Visit www.abc-clio.com for details.

Libraries Unlimited

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

by Joel Silver

Foreword

It is really all about the books. And the manuscripts. And the photographs, and sheet music, and ephemera, and objects, and everything else that combine to make a rare book and special collections library. Until recently, collecting physical objects was what all libraries routinely did. A library was based on its physical collections, and the librarians assembled and developed those collections, and they also made sure that people were able to use them. The focus in non-special-collections libraries was on information, and the information was found in books. As libraries ran out of space, and as they embraced newer technologies, the provision of information in the form of microfilm and microfiche became standard in research libraries, and many older books and runs of periodicals were made available this way. If, however, a library did not have a requested work in any form, it could and would borrow it, unless the book was rare and therefore not available on interlibrary loan.

What made librarians consider a book to be rare? Sometimes it was the age of the book, or its relatively high financial value. On other occasions a book was designated as rare because it was a limited edition or it was in a special binding, or it was signed by the author or another well-known person. As institutions gathered enough of these rare books, it became clear that they needed to be physically separated from their circulating companions, and that they also needed special care so that they would not be lost or damaged. Special expertise was required as well on the parts of their caretakers, so that the books could be described properly and then made available to inquiring readers in an appropriate and secure environment.

As more special collections departments and libraries opened in American academic institutions, owning rare books and manuscripts became an accepted and necessary activity for many libraries. The books were there to provide information, and they could also be used to show the history of writing and printing, as well as to provide tangible support for the study of how and what our ancestors wrote and read. Special collections librarians were well aware of the importance and high value of their collections, and they worked to build their holdings through purchase and gift, and to make them available to interested and qualified readers who had the need to consult their holdings. Librarians also mounted exhibitions, published catalogs, arranged for talks and conferences, and spent a great deal of time learning about their collections and answering questions related to them.

Over the last half-century, the profession of special collections librarianship in the United States has grown tremendously, as special collections librarians have worked to organize and define themselves as a separate branch of librarianship, distinct from other specialties in its focus on original objects, but similar to other areas of librarianship in its insistence on the highest standards of service and expertise. During this formative period of special collections librarianship, however, the rest of the world of librarianship did not remain static. The tremendous growth of the use of electronic technology in all parts of society, including libraries and librarianship, has transformed libraries irrevocably from reading and reference rooms with supporting collections of books to providers of information in whatever form can best serve users needs. In the academic world, it is now usually information in electronic form that users are seeking, and a prospective library user might consider that the best outcome to an inquiry is that the necessary information and resources can be provided without any need to visit the library in a physical sense. Users have come to expect, and librarians are striving to provide, as much information as possible in electronic form. Physical books are still being purchased, but more library users are expecting that the books that they want or need to read will be made available to them in free and searchable electronic form, suitable for any electronic devices they may own now or in the future, from cell phone to portable e-reader.

What does this mean for special collections libraries? Most importantly, rare book and special collections librarians inhabit a world of librarianship in which user access to all of a librarys collectionsthe more immediate the access, the betteris paramount. While previous generations of rare book librarians tended to focus on the building of their collections above all else, today it is access to and communication about the collections that occupy a greater portion of librarians time. Certainly, collection development has not been forgotten, and librarians, even with their often-reduced acquisitions budgets, continue to make significant additions to their collections. But the ease and expectation of swift electronic communication has changed the way rare book librarians now go about their business, and as