Contents

Guide

Page List

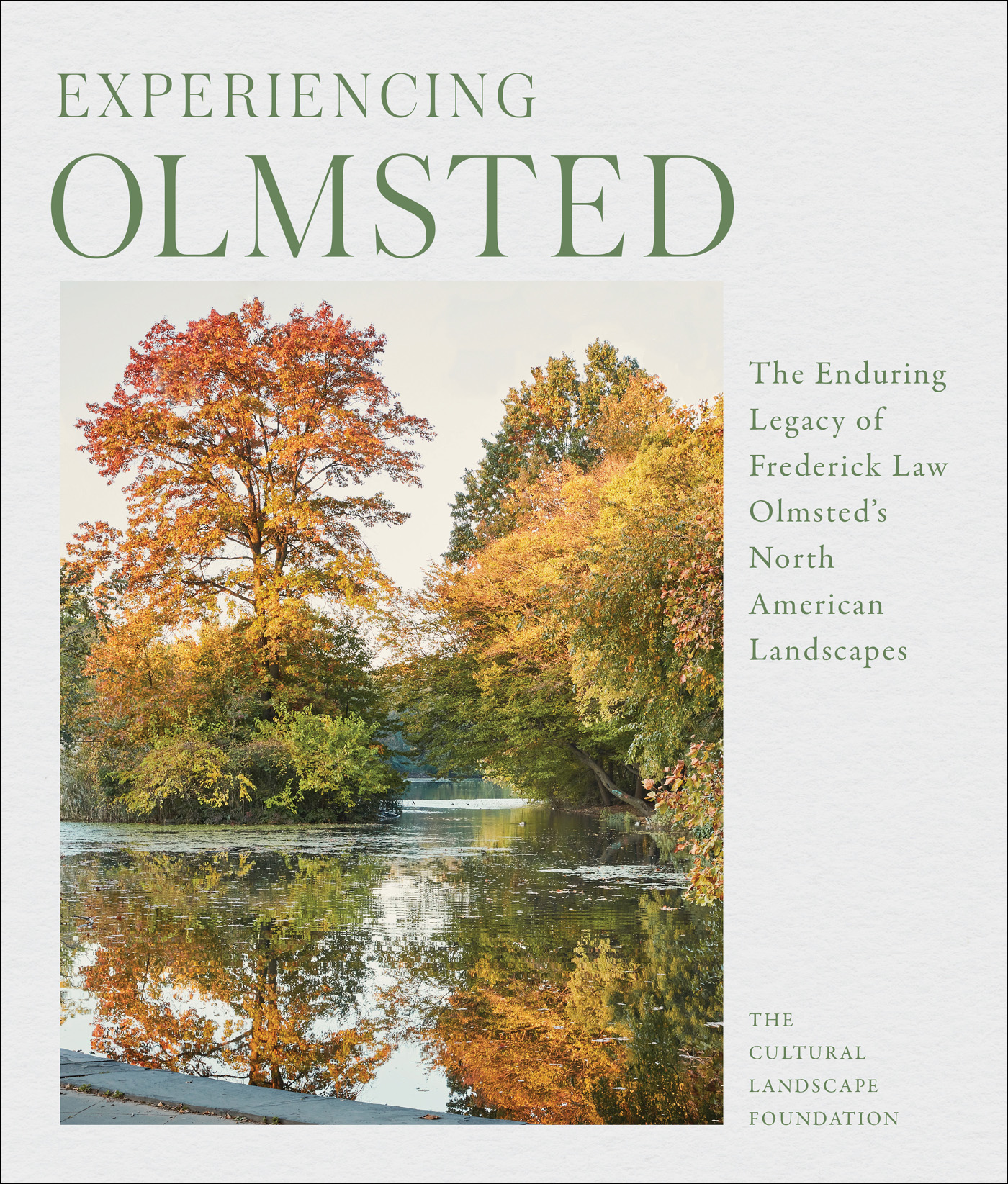

EXPERIENCING

OLMSTED

The Enduring Legacy of Frederick Law Olmsteds North American Landscapes

THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE FOUNDATION

CHARLES A. BIRNBAUM, ARLEYN A. LEVEE, AND DENA TASSE-WINTER

TIMBER PRESS

PORTLAND, OREGON

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

EXPERIENCING OLMSTED

Charles A. Birnbaum, FASLA

Experiencing an Olmsted landscape can alter your mood, calm your spirit, and provide lifelong memories. Distinct from fine art, architecture, music, and dance, a great work of landscape architecturefrom a meticulously planned and designed park or garden to an expansive open space preserved as a natural or scenic reservationis uniquely multisensory and utterly transporting.

In her 1893 treatise Art Out-Of-Doors (written just two years before Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.s retirement from practice), Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer reflected on designed landscapes as an art form, noting, The Arts of Design are usually named as three: architecture, sculpture and painting. It is a popular belief that a man who practices one of these is an artist, and the other men who work with forms and colors are at the best but artisans. Yet there is a fourth Art of Design which well deserves to rank with them, for it demands quite as much in the way of aesthetic feeling, creative power, and executive skill. This is the art which creates beautiful compositions upon the surface of the ground.... The mere statement of its purpose should show that it is truly an art.

Van Rensselaer goes even further in her preface, proclaiming, It is one which has produced the most remarkable artist yet born in America; and this is reason enough why Mr. Olmsteds fellow-countrymen ought to try to understand its aims and methods.

Following Olmsted Sr.s death in 1903, during the next half century, the firm he founded was led by his nephew and stepson, John Charles Olmsted (18521920), and his son, Frederick Rick Law Olmsted Jr. (18701957). After John Charles Olmsteds death in 1920, Rick ran the firm until his retirement in 1949, and remained a partner until his death (see selected staff biographies of the Olmsted firms at the end of this book). While the thousands of projects undertaken in these yearsa cross section of which are included in this volumewere produced under the mantle of the firm name, here we have endeavored to illuminate the involvement of the individual talented practitioners employed by the firm, whose creative interpretations enhanced each landscape. Although the Olmsted firm remained active until 1979 under the leadership of Artemas Partridge Richardson II and Joseph George Hudak, the projects during that period reflected contemporary realities such as limited acreage and more demanding recreational needs, a different set of circumstances than the firm encountered in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

In the postwar era, a lack of appreciation for the historic built legacy of the earlier century of practice led to neglect, subdivision, or at worst, erasure.

Fortunately, during the last forty-plus years, much has been done to make Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.s pioneering approach to the art of landscape architecturenamely, planning, design, and stewardshipmore visible and publicly accessible. The result is a new golden age for Olmsted.

This new era is marked by the founding of a dedicated nonprofit, the National Association for Olmsted Parks, and the designation of Fairsted, the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site (FLONHS) in Brookline, MA, as a unit of the National Park Service. Both events took place in 1980, the same year that the Central Park Conservancy was created in New York City. Fundamental to the work of these entities, and the rediscovery of the Olmsted design legacy, are the extraordinarily rich Olmsted archives.

Fairsted houses what is probably the most significant landscape architectural archive in the country, if not the world. Spanning the 1850s to 1980, the collection of professional office records of the Olmsted firms includes more than 6000 projects and contains approximately 138,000 plans and drawings. The collection also includes 100,000 photographs and lithographs, 70,000 pages of plant lists, numerous files of project correspondence, business records, and other ephemera. Essential complementary collections are the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers and the Olmsted Associates Records at the United States Library of Congress. These collections (the latter as of yet only partially digitized) contain more than 173,000 items, including business correspondence and reports, newspaper clippings, drawings, photographs, and more, all illuminating the design intent and historical context for both the landscape architects and their patrons.

Buoyed and enabled by these unrivaled archives (noted in the bibliography of this book) is a treasure trove of publications created for many different audiences: in-depth scholarship (for example, the twelve-volume series of the Frederick Law Olmsted Papers project started in 1972 and completed in 2020), and numerous articles and analyses in academic journals and collections; site-specific publications for myriad Olmsted landscape typologies, including parks, subdivisions, institutional grounds, and much more (including Fresh Pond: The History of a Cambridge Landscape, Jill Sinclair, 2012, and San Franciscos St. Frances Wood, Richard Brandi, 2012); exhibitions at museums, universities, historical societies, and other institutions (Art of the Olmsted Landscape, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, and elsewhere, 19811983, and Viewing Olmsted: Photographs by Robert Burley, Lee Friedlander and Geoffrey James, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, Canada, 1996 to 1997); documentaries (Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing America, 2014, and Olmsted and Americas Urban Parks, 2011), park and open space surveys conducted at statewide, regional, and municipal levels (including Dayton, OH; Rochester, NY; Massachusetts, and Maine); popular histories about Olmsted Sr. or where he appears as a central character (A Clearing in the Distance, Witold Rybczynski, 1999, and Devil in the White City, Erik Larson, 2003); coffee table books (Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing the American Landscape, Charles E. Beveridge and Paul Rocheleau, 2005); and even books for children (Parks for the People: Frederick Law Olmsted, Julie Dunlap, 1994). Online databases have been developed to enable easier exploration for both scholars and travelers of this extensive nationwide legacy of designed spaces. The name Olmsted has achieved such currency that even real-estate advertisements include it in a propertys provenance as a client enticement. And lets not forget that both Olmsted Sr. and Jr. wrote and published extensively, providing a deep and wide historical record that documents their design philosophies, ambitions, and often site-specific design intentions.

With this expansive primary and secondary resource knowledge base facilitating greater attention to the Olmsted firms design legacy, a body of research, analysis, and revitalization project work followed, ushering in an ever-expanding Olmsted renaissance. Landscape histories and historic-cultural landscape reports undertaken by leading landscape architects and historians, aided by federal and state government agencies, conservancies and friends groups, and local residents and funders continued for the next decades, establishing a planning and design approach not just for Olmsted-designed landscapes, but for the broader emerging landscape preservation discipline in search of such strategies and tools.