Praise for Unsettling: Surviving Extinction Together

In her love letter to the environment, Elizabeth Weinberg threads through geography, plant, and animal existence to dislocate and relocate some of our colonizing mythologies in order to reconnect humans to the planet. Moving through a queer, feminist lens, readers can begin to radically rethink the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. A triumph of ecological imagination.

Lidia Yuknavitch, national bestselling author of The Book of Joan and The Chronology of Water

From the gigantic glory of whale poop to the humbling majesty of Denali, Elizabeth Weinbergs Unsettling is a wonderfully scientific and passionately personal exploration of the intertwining human disasters of climate change and lack of social justice. Required reading for anyone thinking we are the dominant species.

Jon Scieszka, First US National Ambassador of Childrens Literature, and author of the climate-activist graphic novel series AstroNuts

Deeply researched and beautifully written, Unsettling deftly weaves memoir, history, and science to chronicle all we have lost: species, rivers, forests, Indigenous cultures and peoples, and our place in a living landscape. But in braiding Weinbergs own coming-out story with her profound connections to the world around her, Unsettling also presents a path away from an antagonistic relationship to the natural world and toward a fluid, equitable, and hopeful future.

Maya Sonenberg, author of Bad Mothers, Bad Daughters (winner of the Richard Sullivan Prize for Fiction)

Facing the severe realities of climate change can be overwhelming. Elizabeth Weinbergs dazzling book crafts a welcome entry ramp, inviting readers on a deeply researched, wonder-filled, big-hearted exploration. She weaves science, history, social justice, and personal growth into elegant nature writing with a conscience. Weinberg is a compelling tour guide, deepening our connection to the planet and one another.

Hannah Malvin, founder and director of Pride Outside

Its too late are hopeless words that make us either fade back into the dissonance between humanity and the natural world or burn out in climate grief. Unsettling reminds us that beauty has not just existed but persists . Weinberg asks us what might happen if we meet each others gaze, grieve what is lost, and resist the certain doom of Its too late, to be the heroes we each need in what still is and what will be.

Jenny Bruso, founder of Unlikely Hikers

At once a celebration of our world, a Jeremiad, and a memoir, Unsettling: Surviving Extinction Together makes the stakes of climate change devastatingly clear. Whether shes illuminating the biodiversity of the site of a whalefall in the deep sea or the scale of the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets or the traumatized resilience of urban coyotes, Elizabeth Weinberg is a passionate advocate for the ways in which were going to have to reconceive our very relation to the planet in order to become our own heroes and turn aside oncoming catastrophe.

Jim Shepard, author of Like Youd Understand, Anyway and Phase Six

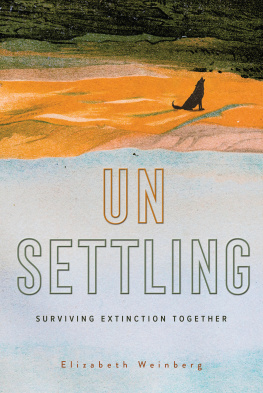

UNSETTLING

UNSETTLING

Surviving Extinction Together

Elizabeth Weinberg

Broadleaf Books

Minneapolis

UNSETTLING

Surviving Extinction Together

Copyright 2022 Elizabeth Weinberg. Printed by Broadleaf Books, an imprint of 1517 Media. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Email copyright@1517.media or write to Permissions, Broadleaf Books, PO Box 1209, Minneapolis, MN 55440-1209.

Cover image: Landscape: Nastasic/iStock; coyote: SlothAstronaut/iStock

Cover design: Michele Lenger

Print ISBN: 978-1-5064-8205-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-5064-8206-4

For Leslie

Contents

Off the coast of Oregon, a gray whale swims along the seafloor, bumping and scraping her head along the bottom of the ocean, loosening the soft sediment into a dense, waterborne cloud. She gulps in a mouthful of the muddy water, briefly savoring its earthy, salty taste, then forces it out through the hairy baleen hanging from her upper jaw. She scrapes the crustaceans left behind off with her tongue and slurps them down. She surfaces for a breath, then dives to feed again.

Off the coast of Oregon, that same whale logs at the surface, half asleep and breathing through the twin holes on the top of her head. She sighs, and steam rises into the air. Then, from the other end of her body, she lets out a mighty plume of digested invertebrates. All that protein has to go someplace, after all.

This whale friend of ours is massive, nearly fifty feet long. Shes eaten more than a ton of food today. Her poop is prodigious.

Whales like her are so big, and so numerous, that their excrement drives entire ecosystems. Many species eat deep underwater, then defecate at the surface. Scientists describe their poop as flocculent , meaning wooly, like the tufts and curls adorning sheep. The loose, clumping nature of whale poop allows it to float, a mass of nutrients bobbing along the water like so many little sheep.

But it doesnt stay there for long. Bacteria and algae consume the nutrients and grow, then are eaten by small invertebrates and fish. Those, in turn, are eaten by larger fish and seabirds, which are then eaten by sharks, sea lions, and whales, until whale poop is fueling a whole web within the ocean. Scientists call it the whale pump.

Its just shit, sure. But as so often seems to happen in the natural world, the pieces that seem least significant are the most important.

And the whale, so often thought of as the tip-top of the food chain, also drives the bottom of it. Because why live a life thats just one thing?

Most adult baleen whales only eat for half the year. They spend the summers at high latitudes gorging themselves on krill and fish, building up their fat reserves, then journey thousands of miles to the tropics or subtropics to mate or give birth over the winter. The lower latitudes have fewer predators, making them a safe place to rear a vulnerable newborn, but they are also, for the most part, devoid of food. During these sun-warmed winters, whales will fast for months on end.

For several years, I worked as a science writer for a system of marine protected areas in the United States, including one that protects the breeding and calving grounds of thousands of humpback whales in Hawaii. Most of my work was remote, and I rarely got into the field. But when I did get to go to Hawaii, my spouse Leslie and I tacked on a vacation, including a day of whale watching and snorkeling. A catamaran took us off the coast of Maui early in the morning, and we had been motoring for about half an hour when the captain cut the engine. In the stillness, a puff of fog rose into the air, and then, there they werea mother humpback whale and her calf, resting together.

It was the first time Id seen whales in person, and I wanted to dance and to cry. They were so big , even the baby. And despite all wed put whales throughcenturies of whaling, noise pollution, climate changethey were here, and they were together.

That was in 2017, and though I didnt realize it at the time, seeing that mother and calf was even more miraculous than it felt. Beginning in 2015, fewer whales began showing up in Hawaii each year, and those who were spotted were mostly males. In 2017, the Hawaii Marine Mammal Consortium only sighted six calves in its annual survey of the Big Islands Kohala Coast.

Researchers are still trying to figure out why the whale numbers dropped, but it seems to be linked to food availability: thanks to a combination of climate change and El Nio, conditions in the North Pacific were particularly hostile to krill and other humpback whale food sources in those years. With less food in their Alaska feeding grounds, whales probably couldnt build up their fat reserves, and the females either skipped the breeding season and stayed up north to eator they died. Either way: fewer whales in Hawaii.

Next page