Introduction: Roman Women in Early Modern English Drama

Domenico Lovascio

Appellata est enim ex viro virtus, explains Cicero in Tusculanae Disputationes (first century BCE): virtus takes its name from vir, the Latin for man. The ideal of virtus, embracing a much broader assortment of values than the current notion of virtue, was a foundational staple of Roman society and was viewed as the (almost) exclusive province of men. Building on Cicero (and Varro), Lactantiusa Christian scholar who became an advisor to the first Christian Roman emperor, Constantine Iwould argue a few centuries later in De opificio Dei (third through fourth centuries CE) that Vir itaque nominatus est, quod maior in eo vis est quam in femina; et hinc virtus nomen accepit. Item mulier (ut Varro interpretatur) a mollitie, immutata et detracta littera, velut mollier. Simply put, Lactantius contends that men are stronger than women, and so they gave virtus its name; woman, on the contrary, takes her name, mulier, from weakness itself. Accordingly, women cannot really aspire to virtus: they just lack the necessary strength. The uttermost to which they can tend is living by the ideal of pudicitia, that is, chastity. Thus, the arena in which mens virtus should ideally be put to the test is war; the arena in which women are supposed to test their pudicitia is sex.

In general terms, such a conception of the gender landscape of the society of ancient Rome widely penetrated the early modern English social imagination, which saw ancient Rome as a model for art, culture, politics, military technique, and, especially, masculinity. The Roman man was simply the best man there could exist: disciplined, loyal, strong, constant, and, above all, in control of himself. As Clifford J. Ronan famously remarked, Roman meant man to the superlative degree: stereotypically masculine man the ruler, the killer, the Stoic, the builder, the wielder of wordssomeone self-secure enough to protect (when so inclined) weak and vulnerable females, children, subject peoples, or artists. Hence, the plays with a Roman setting produced for the early modern playhouses seem to have appealed especially to a male audience that relished the opportunity to watch a compelling and inspiring array of masculine virtues enacted on a stage by male players acting renowned male personalities from the Roman past on the backdrop of well-known momentous events in Roman history. By and large, it would be difficult to deny that the manly sphere is far more fully developed than the female one in the early modern English plays set in Rome.

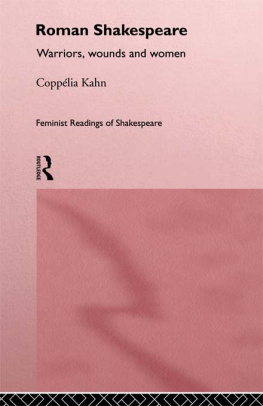

Small wonder, then, that, when it comes to scholarly discussions of the Roman plays of the period, the attention is predominantly focused on male characters, masculine roles in society, and manly systems of values, with the partial exception of William Shakespeares plays. I say partial because, even though Shakespeares Roman women have been the subject of numerous thought-provoking critical contributions in the form of journal articles and book chapters, there is no book-length study dealing systematically with Roman female characters across Shakespeares entire Roman corpus apart from Copplia Kahns landmark Roman Shakespeare: Warriors, Wounds and Women. Over twenty years have gone by, but nothing even remotely comparable to Kahns study has been produced in this period on Roman women in Shakespeare or any of his contemporaries, whereas, for example, the Greek women and the European women of early modern English drama have been recently dealt with in a monograph and a special journal issue respectively.

At a time in which the reception of the Roman past in early modern English literature and culture shines as a particularly thriving area of inquiry, it seems rather odd that no monograph study or edited collection has emerged focusing on the Roman women of early modern English drama. Thousands of pages have been written in the past three decades on Roman male characters as well as on non-Roman women in early modern English drama (e.g., Cleopatra, Boudicca, Dido, Cordelia, Desdemona, etc.); nevertheless, little has emerged regarding what makes Roman women Roman and what their role in those plays is beyond their supposed function as supporting characters or even mere backdrops for the male protagonists. In other words, as Lisa Hopkins and I lamented in 2016 in the introduction to the thematic issue of Textus. English Studies in Italy on The Uses of Rome in English Renaissance Drama, it seems legitimate to argue that not enough has been done about what might be gathered about the representation of female characters in the specific context of Roman drama, especially given that the narrative of the founding of the Republic was centrally bound up with the story of a woman, Lucrece. At the time, Hopkins and I formulated a number of questions that we perceived as especially urgent:

Do female characters in Roman plays feature the same traits that can be found in other genres or do they present any peculiar traits? Does the Roman ideal of virtus in any way clash with the popular stereotype of woman as invariably disorderly and possessed with an insatiable sexual appetite? Are Roman female characters somehow special in early modern English drama? Do the portrayals of women in Roman drama mirror to any extent the actual condition of English women by projecting English values onto their implicit judgments or do they in fact constitute a privileged venue in which to project desires and aspirations about women through the creation of idealised female characters?

Such questions, however, could be only tangentially answered by the contributions in that venue, because, for several reasons, we could not focus exclusively on women. Hence, I decided to embark on a further, more targeted exploration of such issues in order to contribute to filling this critical gap through the present collection, which welcomes the voices of ten young and promising Italian scholars (three of whom had already contributed to the aforementioned thematic issue of Textus) with a view to further complicating and problematizing our understanding of the conception of the Roman world and of women in early modern English drama.

That the Roman women of early modern English drama have attracted so little scholarly attention is arguably all the more striking in light of the fact that Gender Studies and Womens Studies are now firmly established critical avenues. The reason behind this gap is possibly to be attributed to some sort of critical misconception that there may be no satisfactory insights to be gained by subjecting Roman women to the same scrutiny that has been reserved for Roman men in early modern English plays. According to Ronan, As for Roman women, they are sometimes patronizingly termed masculine, but oftener freakish, whorish, or ripe for being violated and victimized. Stage Romes obvious inability to treat women as people thus points to an instability, a hollowness, in two cultures: the Ancient and the Early Modern. Ronans curious idea that the early modern Roman plays were