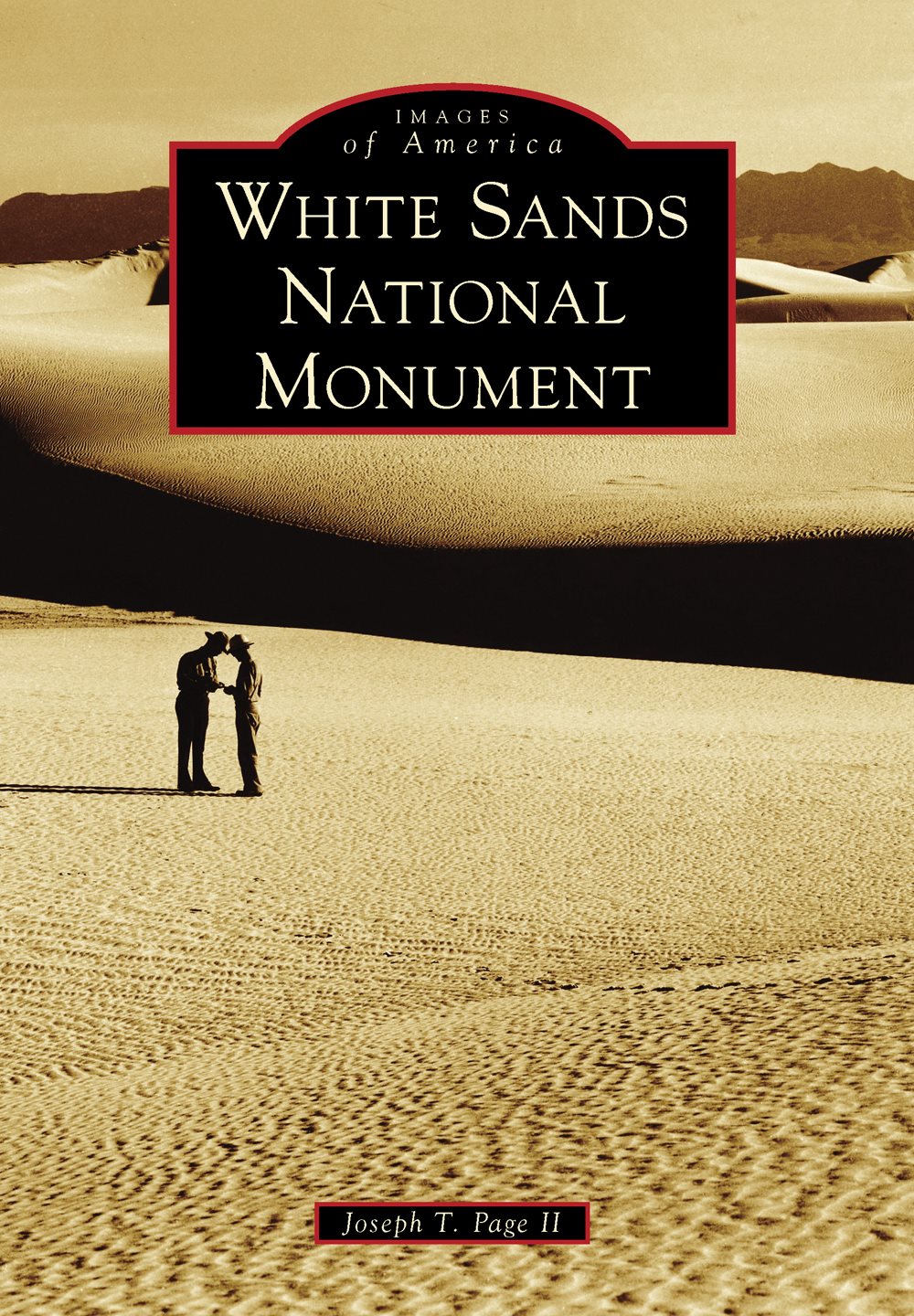

IMAGES

of America

WHITE SANDS

NATIONAL

MONUMENT

ON THE COVER: As a dome dune rises in the background, two National Park Service (NPS) employees converse while standing atop large swaths of gypsum. (Courtesy of White Sands National Monument archives.)

IMAGES

of America

WHITE SANDS

NATIONAL

MONUMENT

Joseph T. Page II

Copyright 2013 by Joseph T. Page II

ISBN 978-1-4671-3064-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439644362

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946957

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Melissa OBrien Shroka (19782013).

Always a true friend, ready with a smile, hug, and a sympathetic ear. Know that you are missed.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project could not have been completed without the help of the National Park Services White Sands National Monument (WSNM) team: Superintendent Marie Frias-Sauter, Chief of Natural and Cultural Resources David Bustos, Chief of Interpretation Rebecca Wiles, and Western National Parks Associations park store manager Anette Dunshee.

Id also like to thank the following for their invaluable assistance: Jean Ann Killer and Don Larson (Tularosa Basin Historical Society); Director Chris Orwoll, George House, and Mike Shinaberry (New Mexico Museum of Space History); Director Darren Court (White Sands Missile Range Museum); and Erin E. Gaberlavage, for donation of her amazing photographs.

Thanks to Stacia Bannerman and all of the professionals at Arcadia Publishing for taking a chance on this book.

Thank you to my wife, Kim, for being my soul mate and nexus during this project; thank you to my children, for keeping me centered and distracted at the right times; thank you to my sister Erin and brother-in-law Robert, for sharing the New Mexican experience with me; and thank you to my parents, Joe and Kathy, for love and support.

Unless otherwise credited, all photographs are from White Sands National Monuments photographic archive. Any errors within the text are the sole responsibility of the author.

INTRODUCTION

Formal recognition of the uniqueness of the white sand gypsum dune field in southern New Mexico occurred on January 18, 1933, when Pres. Herbert Hoover, acting under the authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906, proclaimed and established a White Sands National Monument. The monuments story, however, can be traced to the waning years of the 19th century and is linked to the nationwide growth of the national park idea that followed the establishment of Yellowstone National Park in 1872.

The year 1876 marked the grand centennial for the United States, and the young nation was concerned about a perceived lack of a cultural heritage to equal the European standard. Unable to match the traditional measures of art, architecture, or literature, American nationalists seized upon the grand scenic vistas, particularly found in the American West, as a source of national pride. As the century neared its close, these treasures were increasingly included in national parks.

The economic benefit derived from park status was not lost on early promoters either. Parks brought visitors who would require a variety of services that translated into businesses and jobs. Following the Yellowstone Act, other park proposals proliferated as politicians sought a similar resource for their districts. Southern New Mexico is no exception. As early as 1898, a Sacramento Mountains National Park was suggested, but when organizers learned that their desire for a hunting preserve did not fit with the national park mission, the direction changed and the area became part of the Lincoln Forest Preserve in 1902.

The next national park notion surfaced in 1912 in the form of a bill sponsored by newly appointed senator A.B. Fall. His suggestion for a Mescalero National Park did not receive much support, but it kept the idea alive. By 1921, Senator Fall had moved on to the position of secretary of the interior and proposed the most ambitious park plan to date. The idea was to form an all-weather national park from a variety of public and private lands including a part of the Mescalero Indian Reservation, the Malpais lava flow near Carrizozo, all of the white sands dune field, White Mountain, and Elephant Butte Reservoir and lake. This idea managed to offend almost everybody and the plan quickly faded, but it did focus attention on the dune field, which was judged the one component with real potential for park status.

That potential coincided with the dream of a determined group of local promoters who had long sought to attract development in the Alamogordo area to capitalize on the dune resource. Many proposals had been submitted regarding commercial development of the gypsum found in the dunes.

The enthusiasm of Tom Charles, one of the leaders of the boosters, for the project was contagious and his perceptions about the value of the dunes were proved accurate. Interest in national recognition for the resource grew throughout the latter part of the 1920s. Studies were conducted by the National Park Service, which determined that while the dunes might not meet the criteria for national park status, which required a variety of resource values, the setting was ideal for preservation as a national monument. With the full backing of the New Mexico congressional delegation, as well as the support of communities from El Paso to Roswell, success was achieved in the waning hours of the Hoover administration.

In some ways the timing was fortuitous, for the establishment of the monument coincided with the dark days of the Great Depression and the economic recovery programs of the Roosevelt administration. Works Progress Administration (WPA) funds were used to improve many park areas, and White Sands benefited by achieving a full measure of development within just a few years of opening. Construction projects included the visitor center/administrative building, maintenance facilities, public restrooms, and park residences. All of these buildings are still in service.

As evidenced by visitation numbers over the decades, interest in the monument is proof of the clear vision shown by early park boosters. In its first year, the area attracted 12,000 people. By 1948, the number increased to more than 100,000 per year. The year 1957 marked the first time that visitation topped 300,000, and by 1965, more than 500,000 people were coming to the park each year. In four different years, total visitation has exceeded 600,000, the last time as recently as 1986.

Today and in the future, the park staff faces challenges meeting increased demand for services that ever-increasing visitation requires, including ensuring the protection of the resources for which the monument was established. In the months ahead, the park will be revising its management documents in an attempt to come to grips with this preservation vs. use dichotomy. Public input is an important part of this process, particularly on the role of the park in the local economy. The park will also examine its role as a living laboratory for desert research; the potential for new research in paleontology, archeology, and rapid adaptations in desert ecology; and new ways to provide for visitor interaction with desert resources. Further information on this process and the occasions for public involvement will be forthcoming. Local residents are urged to take advantage of these opportunities to help set future directions for this unique and very special place.

Next page