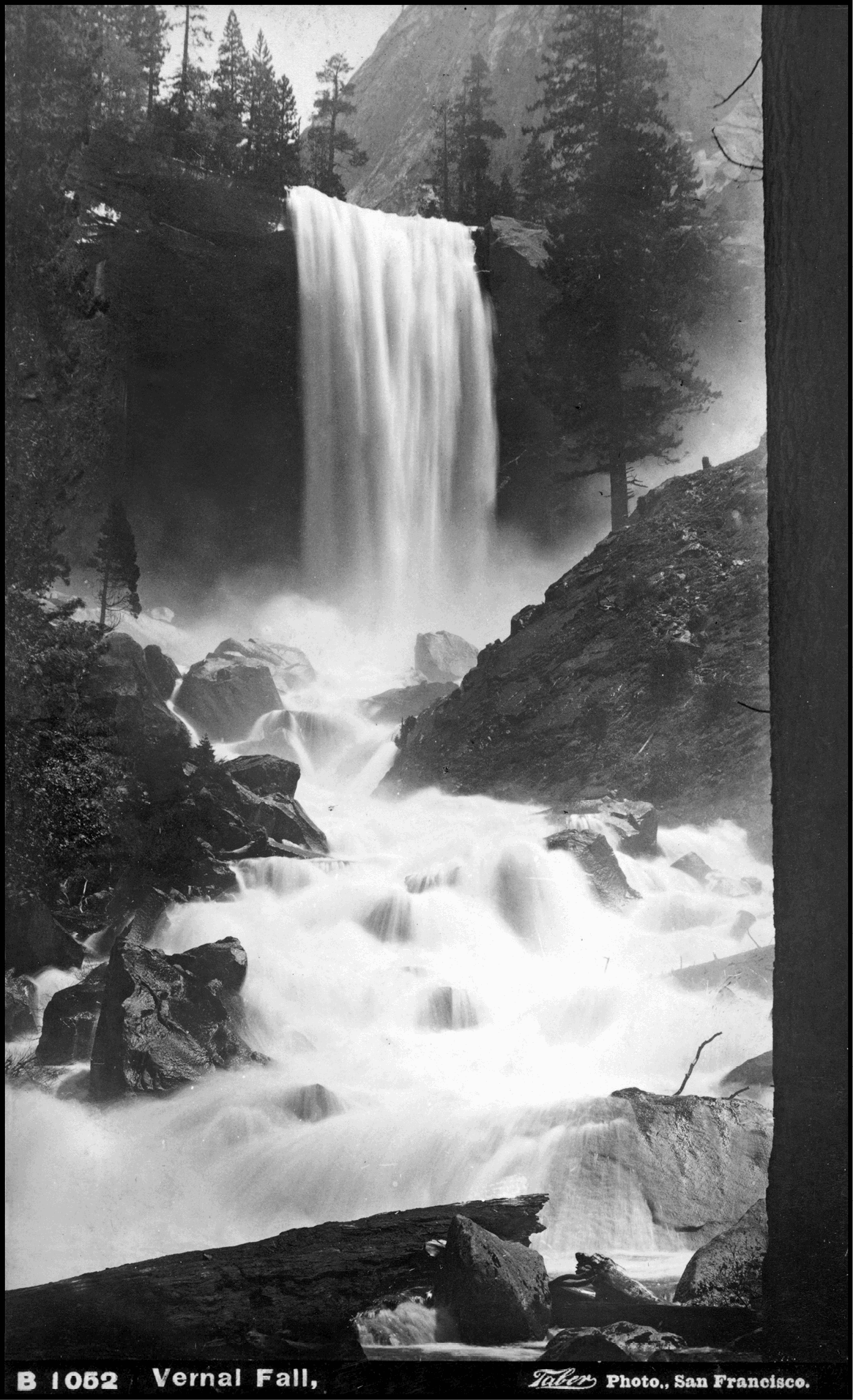

Although reproduced by I. W. Taber, this photograph was probably the work of famed pioneering photographer Carlton E. Watkins

Preface

T he sun was gently sinking in the gold and crimson sky, and my eyes were drawn to the soft silhouette of the western hills beyond the shimmering waters. Reeds bent compliantly before the persistent December winds, and the fragrances of the marsh swirled all about me. The scene was punctuated by the sights and sounds of scattered flocks of migrating ducks and geese. Only Nature can paint such a sublime scene in just the blink of an eye. I was an anxious observeran intruderon the canvas of one of Natures fleeting masterpieces.

As a flock of green-winged teal, among the most beautiful of birds on the wing, came headlong towards me, I sensed something out of the ordinarysomething that I had never felt before. I lowered my 12-gauge shotgun, ejected its shells, and placed it by my side. From the blind next to mine my father asked, Not going to shoot anymore today? Trying to conceal the tears in my eyes, I replied, Never again! Although moments like this had happened to me before, this was the first time that I was conscious of being taught one of Natures essential lessons.

Certain events in a mans life can be especially instructive, as if they were markers along the trail. We dont always immediately recognize these signs, and if we do, it is usually later on in our journey when we are older and wise enough to ponder the meaning of the years. While in Natures world, we might appreciate her movements and her beauty, but we cant possibly predict how a wilderness encounter might alter the course of the rest of our lives. The hunting experience that I have told about took place more than thirty years ago, and I have not fired a gun since; not for any activist reasons, but because I learned something once in a duck blind that opened my eyes to life on a grander scale. Experiences like mine are not uncommon. Many of us have had them.

Parker Palmer, popular Quaker writer and thinker, speaks eloquently of the timeless wisdom underlying Thomas Mertons conception of the hidden wholeness of all things .

In the visible world of Nature, a great truth is concealed in plain sight; diminishment and beauty, darkness and light, death and life are not opposites. They are held together in the paradox of hidden wholeness.

As a young man, Merton became disenchanted with the shallowness of secular society, and being richly influenced by ascetic ideals, he sought his vocation as a monk. During the 1940s and 50s, while living in solitude at the Abbey of Gethsemani, nestled among the trees and hills and streams of rural Kentucky, Merton penned numerous books. These books contain deeply moving accounts of his encounters not only in Nature, but in the wilderness of his soul. Perhaps no writer in recent memory captured the raw essences and the connectedness of wild places more compellingly than did Thomas Merton.

Mertons hidden wholeness is grounded in a profound consciousness of the sublime relationship of all things to one another. Thus, if we seek to become more like whom we were created to beour authentic selvesthen we will have begun to do something vitally important. Lessons of the Wild: Learning from the Wisdom of Nature supposes that we are part of an invisible web of life, and that Natures lessons can help to move us toward becoming better men. Better men make for a better world, and a better world is something worth striving for. Hopefully, this book offers some fresh ways of looking at Nature and challenges the reader to look deeply into his, or her, own inner wilderness.

There are numerous stories in this book, some of which may appear to be more than extraordinary. Perhaps they seem so because most of the characters told about are such ordinary folks. How these people came so fortuitously into my life and why they so willingly shared their journeys, I will never quite comprehend. But I am assured that each of their experiences actually took place and that they have been related in as factual a detail as memory and the passage of time permit. None of the portrayals are fictional, and none of their names have been changed.

Lessons of the Wild is also a book about managing transitions. During my last six years in the corporate world, I counseled men and women who were moving from one stage of their work lives to another. While these life shifts were career related, they had notable reverberations into other aspects of these peoples lives. In many cases, the people I met experienced emotional and psychological distress, followed by periods of remarkable healing. I remain convinced that the lessons we learn in the wild can help prepare us to successfully manage difficult transitionsespecially in the complex passages from childhood to adulthood, and from middle age to an age of wisdom.

I am thankful for a number of influential thinkers, who by their writings have helped to shape my view of life and nurtured in me a richer understanding of my place in the vast expanse of the universe. First and foremost among these thinkers are Thomas Merton and John Muir. Time and again I have been richly rewarded by reading Mertons writings, especially his Seeds of Contemplation . Muirs colorful accounts of his life in the woods are unsurpassed; works, like My First Summer in the Sierra and The Mountains of California , published more than a century ago, are as fresh as a field of diasies. I am indebted to writers like Loren Eiseley, Annie Dillard, Wendell Berry, Rachel Carson, and the many others who have given me their unique insights into the wholeness hidden in all things. Among others, I have borrowed liberally from the wisdom of T. S. Eliot, Parker Palmer, Huston Smith, Robert Bly, Gerald May, John Eldredge, and Richard Rohrevery one a trailblazer in our amazing journey through the wilderness.

My family and friends have heartily endorsed the writing of this book. My wife, Debbie, and our daughters, Michelle and Jennifer, have unwittingly given me the courage to write. Michelle is a college English teacher, who has made me feel worthy as an author and has lovingly kept me focused on the finish line. Some of my fondest memories will always be of days on the softball field and on the trail, hiking and backpacking with Jennifer, who now also has followed her mother into the teaching profession. Books do not get written without great sacrifices being made by those around us. I am particularly grateful to Debbie for sharing so many wonderful years with me and giving me two beautiful children, but also for selflessly granting me so much time in solitude. There is something special about belonging to a family of teachers.