Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the following individuals for fielding questions or for reviewing various parts of the text:

Steve Ferguson, Research Scientist, Department of Fisheries and Oceans

Mark Mallory, Canada Research Chair of Coastal and Wetland Ecosystems, Acadia University

Carolyn Mallory, Author, Common Plants of Nunavut and Common Insects of Nunavut

Shannon Badzinski, Waterfowl Biologist, Canadian Wildlife Service

Justin Buller, Graduate Student Researcher, Arctic lake systems

Published by Inhabit Media Inc. www.inhabitmedia.com

Inhabit Media Inc. (Iqaluit), P.O. Box 11125, Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 1H0 (Toronto), 146A Orchard View Blvd., Toronto, Ontario, M4R 1C3

Design and layout copyright 2012 Inhabit Media Inc. Text copyright 2012 by Mia Pelletier Illustrations copyright 2012 by Sara Ottersttter Map illustration copyright 2012 by John Lightfoot

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrievable system, without written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law.

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program.

Printed by MCRL Overseas Printing Inc. in ShenZhen, China #4236471.

W hile the Arctic appears as a single place on a map, it is a vast land that changes endlessly as you travel across itfrom frozen ocean, icy blue glaciers, and towering mountains to green river valleys, boggy wetlands, and rolling hills. The boundaries of this region are defined in many ways. Some describe the Arctic as the part of the world that lies within the Arctic Circle. This imaginary line circles the globe at the top of the world to mark the place where the sun does not fully rise or set for at least one day of the year. Trace your finger along this line, and you will pass through the northern parts of several countries around the world, including the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut in northern Canada.

The Arctic can also be described as the part of the world that lies above the treeline. As you travel north, trees become smaller and smaller, then seem to vanish entirely as it becomes too difficult for trees to grow. The treeline rises and falls as it winds across the map of northern Canada, and onwards around the globe.

Yet for the Arctic peoples that have lived in this region for thousands of years, the Arctic is simply home. Avati means environment in Inuktitut, the language of the Inuit. While many of the plants and animals found in this book can be found in other parts of the Arctic, well explore the landscapes of Nunavut, the part of the Arctic that means our land.

T he name Arctic comes from the Greek word for bear, arktos. It describes the constellations of stars that you can see in the northern night sky. See their shapes in the starry sky? These are Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, the Great Bear and the Little Bear. These stars shine over the Arctic, the icy wilderness of treeless tundra and frozen ocean that lies at the top of the world.

From a distance, this bare, windswept landscape appears empty. Covered by ice and snow for much of the year, the Arctic winter is long, cold, and dark. Yet spring and summer bring an explosion of life to the Arctic. As the ice retreats from the land and sea, great flocks of birds arrive from the south, the ocean blooms with life, and tundra plants reach for the sun with new leaves, shoots, and berries.

Lets explore the Arctic through the seasons. Well see that the Arctic is not empty at all, but contains many unique habitats, and plants and animals found nowhere else on Earth. From the millions of tiny insects to the great polar bear, each species is an important part of the Arctic web of life, and all species depend on one another in the struggle to survive.

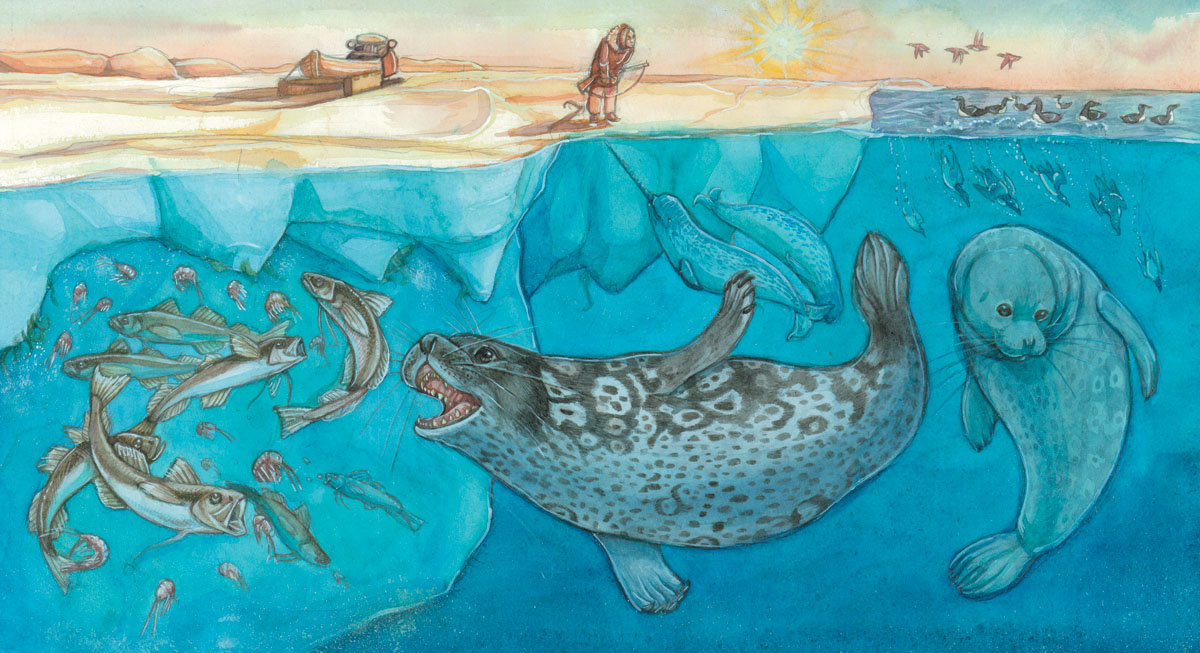

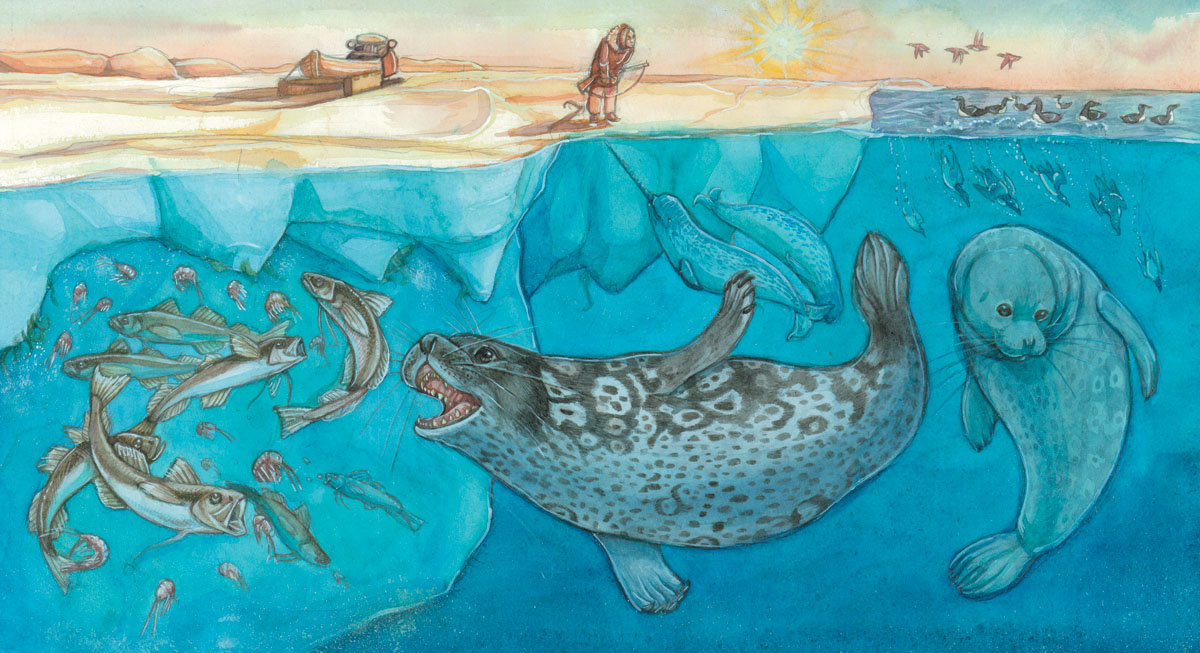

H ere at the floe edge, landfast ice meets open ocean and mist rises in the chilly air. The spring sun has just risen high enough for its light to penetrate the seawater. It shines on the underside of the sea ice, illuminating an underwater garden of tiny algae. Much of the algae that live in the pores and channels on the underside of the ice are made up of diatoms. These algae use energy from the sun to grow so thick that they turn the ice a golden brown. Small, shrimp-like animals called amphipods graze on this rich food. As amphipods eat the ice algae, Arctic cod use their jutting lower jaws to scoop up the amphipods from this hanging garden.

Splash! Gulp! Arctic cod are an important food for many marine mammals, including these ringed seals. Seabirds that have travelled from near and far to the Arctic to nest are also hungry for fish. Thick-billed murres gather in great numbers at the floe edge to dive for the fish they need to build up energy to lay and incubate their eggs. An Inuit hunter has also come to the floe edge to hunt. He listens for the wet breath of narwhals as they glide through the water with their long ivory tusks.

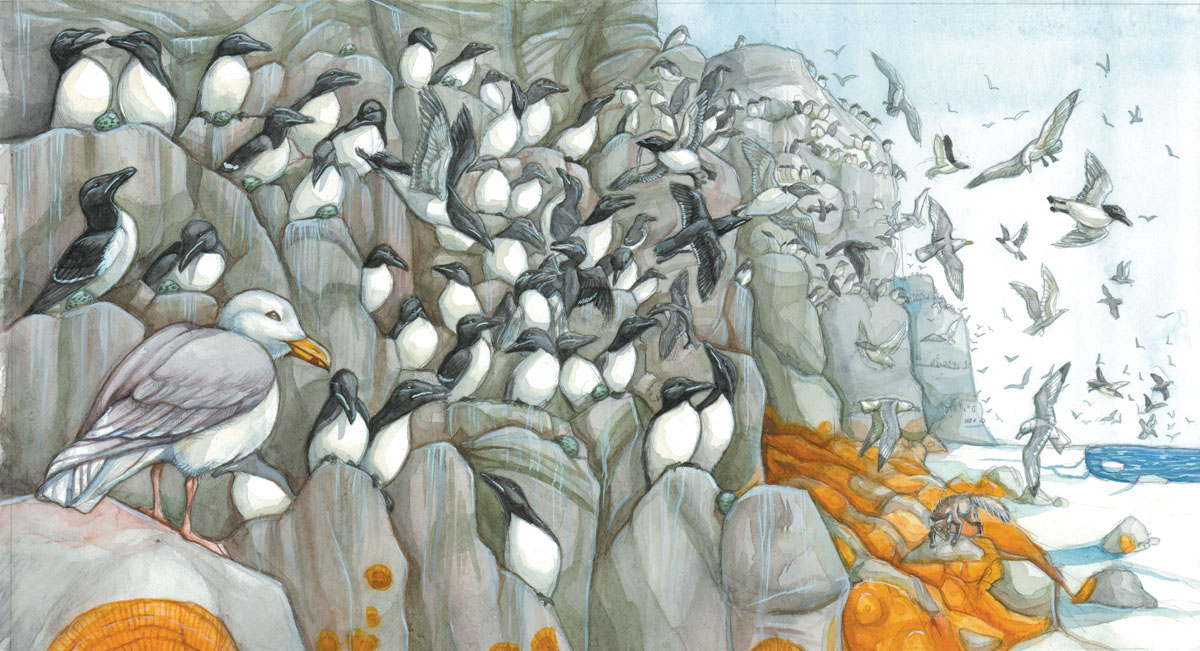

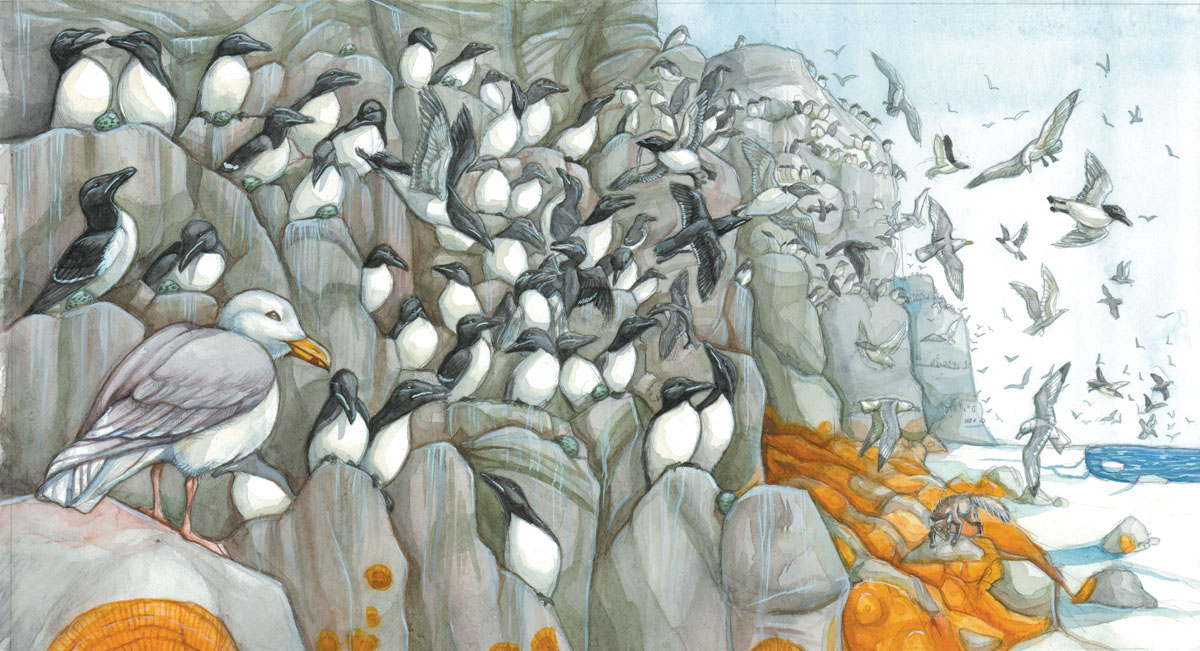

T he sheer cliffs of the Arctic island coasts offer many nesting places for seabirds. After filling their bellies with fish, thick-billed murres head for the sea cliffs to lay their eggs. Aoorrr, aoorr! Murres join the crowded colony, one by one, until the sound of their calls is a continuous roar. Each murre finds its place on a narrow rock ledge to lay its one beautiful, speckled turquoise egg. Pointed on one end and round on the other, their eggs are specially shaped to roll in a circle so they dont fall off the cliff. Hungry glaucous gulls patrol the cliffs like sentries on a castle wall, watching for eggs to steal and eat, while an Arctic fox sniffs the beach below, searching for dropped eggs. Murre droppings provide rich fertilizer for the growth of jewel lichen, which paints the rocks beneath the nest cliffs a brilliant orange.

In early summer, the ocean below the cliffs may still be frozen, and murres must fly out across the sea ice to dive for food in a pool of open water called a polynya. Here, wind and currents keep a patch of ocean free of ice, and upwelling brings nutrients up from the ocean floor. Polynyas are a refuge in the ice for many marine animals throughout the winter, and now they fill with life. Tiny, drifting plants called phytoplankton feed small, drifting animals called zooplankton that, in turn, feed fish and seabirds. Shrimplike krill swim through the water feeding on plankton and provide food for larger animals, like whales. The water teems with life as murres join the northern fulmars and black-legged kittiwakes that have also come to feast. Some murres fly as far as 100 km from their nest cliffs to fish.

Next page