Page List

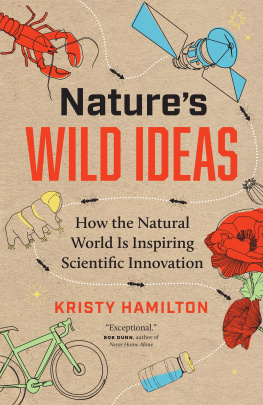

Copyright 2022 by Kristy Hamilton

22 23 24 25 26 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books Ltd.

greystonebooks.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-77164-819-6 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-77164-820-2 (epub)

Editing by Linda Pruessen

Copy editing by Jess Shulman

Proofreading by Meg Yamamoto

Indexing by Stephen Ullstrom

Cover design and composite by Belle Wuthrich and Jessica Sullivan Cover composite illustration credits:

Simple Line, Mikhail Gnatuyk, Crazy nook, jamestar,

Disa_Anna, ujiartdesain, ksanask.art/Shutterstock

Text design by Belle Wuthrich

Greystone Books gratefully acknowledges the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples on whose land our Vancouver head office is located.

Greystone Books thanks the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada for supporting our publishing activities.

To my family and friends. Although many of us may not leave riches to our families, we can bequeath them a legacy more precious than gold, more delicate than glass, and more monumental than fame: a world preserved in the amber of our protection.

Contents

Introduction

Wildly Inspiring

IN 1874, INVENTOR Alexander Graham Bell was a twenty-seven-year-old with a dark, bushy beard working on a world-changing invention, and he was doing so by peering at the swirls of a cadavers ear, an exquisite fleshy instrument that has taken millions of years to develop. Bell was astonished by how the ears thin membrane could move the weight of the middle ear bones: It occurred to me that if a membrane as thin as tissue paper could control the vibration of bones that were, compared to it, of immense size and weight, why should not a larger and thicker membrane be able to vibrate a piece of iron in front of an electromagnet?

Bell had good reason to explore this line of inquiry: both his mother and his wife were deaf, and he taught students with hearing impediments. When he built his ear phon-autograph, he used the actual bones of a human ear mounted on a wood frame. Voices caused the bones to vibrate and visually represent the sound waves as etchings on a smoked-glass plate. The invention was meant to be a tool for his deaf students, but it leapfrogged his imagination to insight that eventually led to his telephone patent in 1876. Sitting in his laboratory, he famously spoke to his assistant on the phone in another room and said, Mr. Watson, come here. I want to see you.

History is rich with such examples: from penicillin derived from fungi to cancer drugs developed from coral to painkillers inspired by venomous frogs and cone snails. Biomimicry (from the Greek bios, meaning life, and mimesis, meaning to imitate) is the study of nature and takes inspiration from its magnum opus of ideas. The first person to coin the term biomimicry (also called bioinspiration and biomimetics) was biophysicist Otto Schmitt, in the 1950s. His idea was popularized in 1997 by biologist and author Janine Benyus, who believes scientists should be at the design table too. Biomimicry is still a relatively nascent discipline, and its important to discern fact from fiction, especially when biomimicry is harnessed as a marketing tool and not as an investment in scientists spending years to gain new insights. Biomimicry is also not a cure for all that ails usit is a guiding light, a source of inspiration, a place of awe where we can marvel at ideas we never conceived of ourselves. In writing this book, my hope is to peer behind the curtains of bio-mimicry and explore the detective work that has occupied thousands of scientists around the worldmen and women who are churning the metaphorical crank of this field ever faster. All around us, creatures millions of years in the making are harnessing energy and materials; they dont produce pollution like us, but they do evolve ingenious solutions to hack their way to survival.

Natures Wild Ideas is about the animals and plants that have inspired everything from telescopes to view cataclysmic explosions in the universe to medication for hard-to-treat diabetic patients to a prize-winning discovery that, according to the Nobel Foundation, has become one of the most important tools used in contemporary bioscience. We can even find human inventions already in use in the animal kingdom: electric eels generate electricity powerful enough to stun a person; squids use jet propulsion; tree crickets turn leaves into mini-megaphones to amplify their calls; and beavers build dams to flood lakes for safe housing and movement. The swim bladder of fish helps them control their buoyancy, similar to the ballast tanks of submarines. Even the agricultural revolution wasnt that, well, revolutionary. Several ant species have long known how to cultivate fungus gardens and herd aphids for their milk, gently stroking them with their antennas to release droplets of honeydew, a sweet fluid they excrete after feasting on sap or leaves. A humpbacks throat is, in essence, large-scale origami, but with folds of skin rather than factory-made paper, expanding thanks to as many as thirty-six grooves that stretch to capture prey and collapse into a compact form when done.

This book is an in-between art: part discovery, part science, part natural world, part philosophical questioning. What is the natural world to us? How important is it that we preserve the diversity of life on Earth? What is our role in the tangled web of creation and innovation? In many ways, nature is more elusive to mimic than we ever imagined. Often we find ourselves trying to extrapolate from the wild and invent something never before seen in the natural world. It takes an interdisciplinary pack of biologists, engineers, chemists, physicists, materials scientists, mathematicians, and more to come together and see the potential. Like explorers poring over the map of an obscure place and wondering what lies in the empty spaces, scientists dig deep into unknown, undrawn places and try to pioneer new insights to add to our collective knowledge. Institutions across the world have added departments solely dedicated to the endeavor of biomimetic science: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Wyss Institute at Harvard, Georgia Techs Center for Biologically Inspired Design, Imperial College Londons Centre for Bio-Inspired Technology, and the Bio-mimicry Center at Arizona State University are but a few.