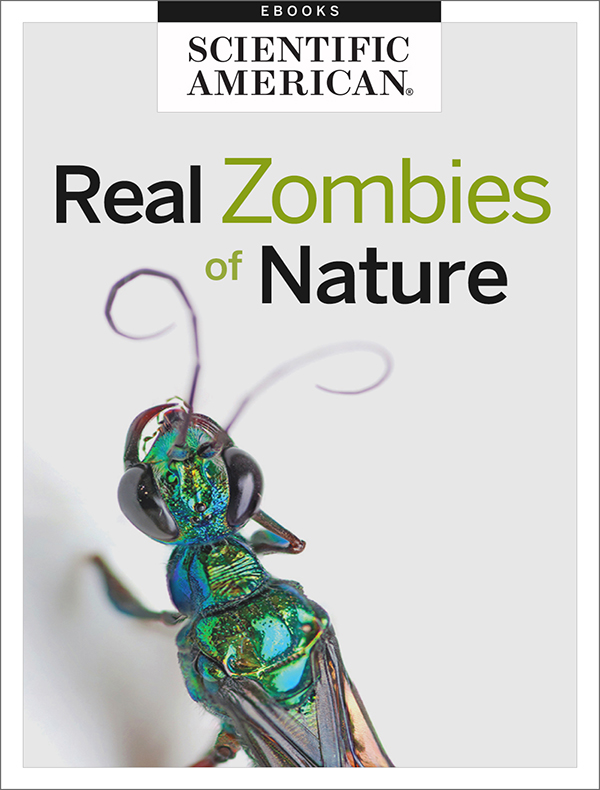

The Real Zombies of Nature

From the Editors of Scientific American

Cover Image: Kimie Shimabukuro/Getty Images

Letters to the Editor

Scientific American

One New York Plaza

Suite 4500

New York, NY 10004-1562

or editors@sciam.com

Copyright 2017 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc.

Scientific American is a registered trademark of Nature America, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published by Scientific American

www.scientificamerican.com

ISBN: 978-1-2501-2155-4

THE REAL ZOMBIES OF NATURE

From the Editors of Scientific American

Table of Contents

Introduction

by Karin Tucker

Section 1

1.1

by Krystal DCosta

1.2

by Melanie Tannebaum

1.3

by Evelyn Lamb

1.4

by Gareth Cook

Section 2

2.1

by Josh Fischman

2.2

by Melanie Tannebaum

Section 3

3.1

by Robert Sapolsky

3.2

by Christof Koch

3.3

by Gustavo Arrizabalaga and Bill Sullivan

3.4

by Moheb Costandi

Section 4

4.1

by Christie Wilcox

4.2

by Katherine Harmon

4.3

by Anna Kuchment

4.4

by Katherine Harmon

4.5

by Katherine Harmon

4.6

by Christie Wilcox

4.7

by Nancy E. Beckage

4.8

by Janice Moore

Zombies: Real and Imagined

Zombies let us explore notions of the apocalypse no water, food, medical care, the government imploding while letting us sleep at night. Max Brooks, author of World War Z and The Zombie Survival Guide.

Of all the monsters of the horror genre, the zombie has had a bit of a renaissance over the last decade. It seems like zombies are everywhere. From recent films like World War Z starring Brad Pitt and The Girl with All the Gifts starring Glenn Close (both adapted from novels of the same name) to enduring TV shows like AMCs The Walking Dead (along with its spinoff Fear the Walking Dead) and Syfys Z Nation weve reached peek zombie saturation in American culture. Communities throughout the country hold zombie runs and races. Even the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention compiled a preparedness guide in case of a zombie apocalypse.

So what drives the fascination with zombies in contemporary American culture? Where did the belief in or fear of this creature originate? Imaginary fears are often based in reality. Are there corresponding behaviors seen in the real world? Is it possible for humans to be taken over by a parasite? In this eBook, The Real Zombies of Nature, we look at the myth versus the reality of the zombie and engage in some scientific speculation about what would happen if the two ever met.

Appropriately, we start by examining Zombie Fever in Section 1, which includes pieces on the origins of the zombie myth and current obsession with the undead. In the opener, The American Fascination with Zombies, author Krystal DCosta unpacks the cultural and religious history of the zombie from its Haitian roots to the reasons why the zombie myth resonates so strongly with us. Later, a mathematician applies a standard epidemiological model to track zombies as a popular culture trend, and two real-world neuroscientists use their expertise to explain behaviors like movement, hunger and cognition in the mythical zombie.

Many scientific disciplines have gotten in on the zombie act. In Section 2, Fighting Real Zombies, Josh Fischman interviews a chemist who has identified the compounds needed to produce an olfactory camouflage to evade zombies. Then, in Avoiding Zombie Attacks with Social Psychology, the author uses the lessons learned from the Kitty Genovese case regarding the bystander effect to increase the chances of survival during a zombie run.

We come back to reality in Sections 3 and 4, which explore various parasites and microorganisms that can infect their hosts and manipulate their neurology and behavior. And yes, there are parasites that affect humans, though none causes cannibalism (so far). For example, Robert Sapolskys Bugs on the Brain looks at rabies and toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii) from a neurological perspective. Other articles provide a deeper examination of T. gondii, how it reproduces and interacts with our nervous system in ways that appear to affect anxiety and stress responses and may have a role in mental illness.

Ants, caterpillars and bees (oh my!) face a truer form of zombification than humans do. In Your Average, Everyday Zombie, Christie Wilcox provides an overview of various parasites that infect insects and literally turn them into the living dead, altering their brain chemistry so that they lose control of their bodies to become slaves of the parasite. These include scroungers like parasitic wasps and barnacles, Phorid flies, hairworms, flukes and even fungus.

The zombie myth has traveled an interesting path from its origins in Haitian folklore to its current prevalence in American pop culture. That these creatures are simultaneously human and not human allows us to explore the themes of human nature, death, othering and societal collapse. Here we ponder what science can tell us about the zombie myth, the natural world and ourselves.

-Karin Tucker

Book Editor

The American Fascination with Zombies

by Krystal DCosta

I think I must be prepared. For what? The impending zombie apocalypse, of course! Surely the plethora of zombie movies, books, survival guides, and even exercise regimens have given me a sense of how to survive in the event of this particular catastrophe. If youve seen even one zombie movie, Id be willing to bet that youre pretty prepared too. If you havent, go watch Zombieland. It provides a fair list of rules that should boost your chances of survival. For example, "When in doubt, know your way out" and "check the backseat" make a lot of sense. Then again, those might be things you should be doing anyway.

Zombies arent pretty creatures. Popular media depicts them in assorted states of decay. They shamble. Theyre insatiable cannibals. And, well, theyre dead. So why cant we get enough of them?

Folklore is home to a host of undead characters: mummies, skeletons, vampires, ghouls, and ghosts can be found under one name or another in almost all mythologies. Though closely linked with Vodoun magic and religion, the zombie is no exception: dybbuks, jumbies, djodjos, and duppies all bear some resemblance to the Haitian zombie, which is a composite of African beliefs transported to the Caribbean via the slave trade (1). Slaves from the Gulf of Guinea transported rites and rituals from the classical East and the Aegean, which took root following Haitis revolution in 1804 (2). This zombie is a complex creature: though, like its cinematic counterpart it lacks consciousness, it is a much more nuanced and manipulated figure. Anthropologist Wade Davis proposed that the Haitian zombie is a pharmacological product created by a bokor (3). A powder created from the toxins found in the puffer fish is administered to induce a lethargic sleep from which the afflicted may be roused and controlled. However, analysis of this powder has yielded frustratingly little information: ingredients appear to vary (including human remains, toads, lizards, millipedes, tarantulas, ground glass, and various plants) as does administration. For example, the powder may be strewn over the path frequented by the intended victim, or on his doorstepthis hardly seems very effective. Haitian traditions allow for the possibility of poisoning, but also posit a supernatural origin: a body is buried and resurrected without causeit is just called by name by a sorcerer and emerges without will, memory, or consciousness, ready to do ones bidding (4). Typically, it will work for its creator, either performing labor or serving as a guard of some sort, and may be rented or loaned.