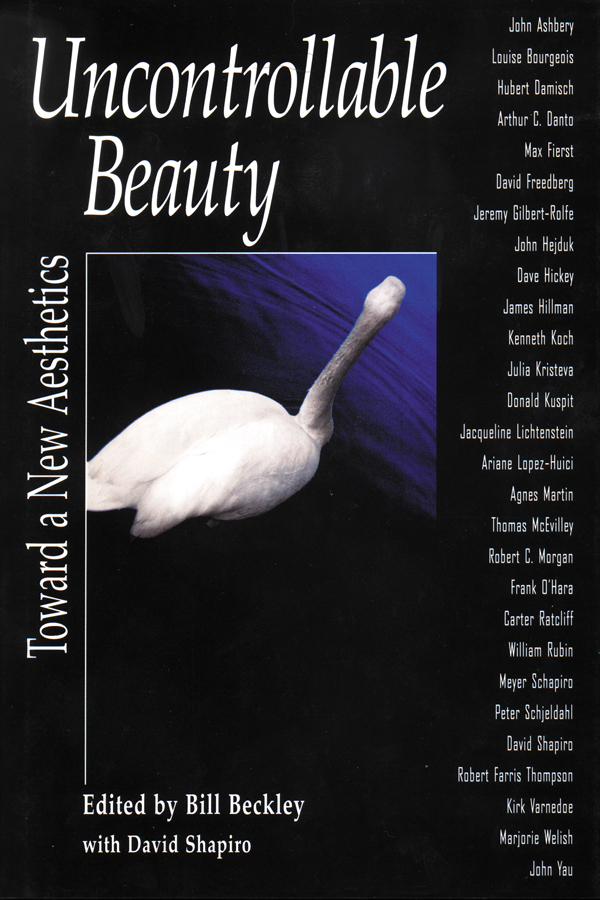

Uncontrollable Beauty

Toward a New Aesthetics

EDITED BY BILL BECKLEY

WITH DAVID SHAPIRO

AESTHETICS TODAY

Editorial Director: Bill Beckley

The Aesthetics Today series includes Sticky Sublime, edited by Bill Beckley Out of the Box, by Carter Ratcliff

Sculpture in the Age of Doubt, by Thomas McEvilley Beauty and The Contemporary Sublime, by Jeremy Gilbert Rolfe The End of The Art World, by Robert C. Morgan Redeeming Art, by Donald Kuspit Dialectic of Decadence, by Donald Kuspit

1998 Bill Beckley

All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan-American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

05 04 03 02 015 4 3 2 1

Published by Allworth Press

An imprint of Allworth Communications

10 East 23rd Street, New York, NY 10010

Copublished with the School of Visual Arts

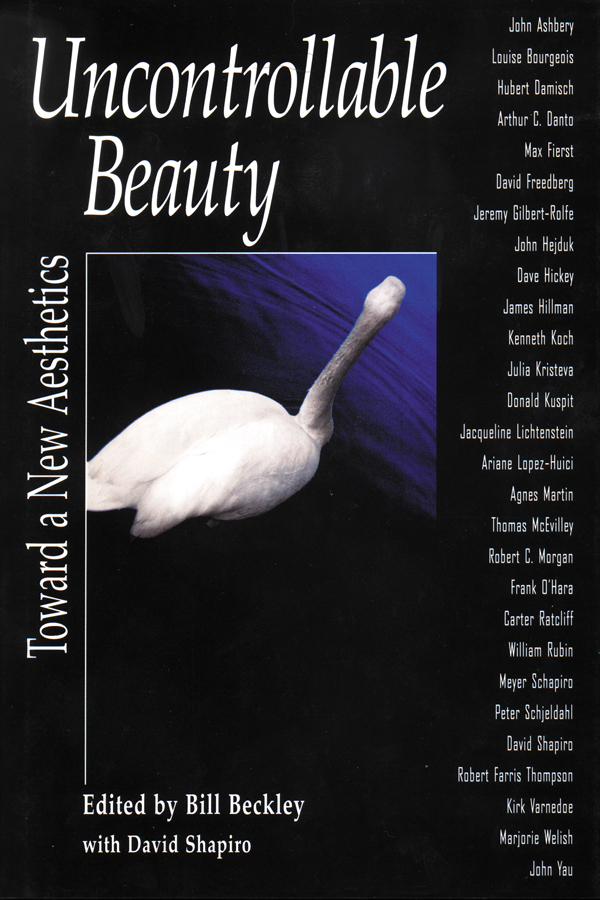

Cover design by Douglas Designs, New York, NY Cover photo 1998 Bill Beckley

Book design by Sharp Designs, Lansing, MI

ISBN: 1-880559-90-0

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-70100

To

SILAS RHODES

and to

TRISTAN, LIAM AND DANIEL

Contents

Bill Beckley

David Shapiro

John Ashbery

Meyer Schapiro

Dave Hickey

Arthur C. Danto

Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe

Peter Schjeldahl

Marjorie Welish

Robert C. Morgan

Jacqueline Lichtenstein

Hubert Damisch

David Freedberg

Thomas McEvilley

letters by William Rubin and Kirk Varnedoe with a reply by Thomas McEvilley

a letter by William Rubin with a reply by Thomas McEvilley

Kirk Varnedoe

James Hillman

Frank OHara

Donald Kuspit

John Yau

David Shapiro

Julia Kristeva and Ariane Lopez-Huici

Louise Bourgeois

John Hejduk

Max Fierst

Kenneth Koch

Robert Farris Thompson

Carter Ratcliff

Agnes Martin

Introduction: Generosity and the Black Swan

BILL BECKLEY

I saw

a swan that had broken out of its cage,

webbed feet clumsy on the cobblestones,

white feathers dragging in the uneven ruts,

and obstinately pecking at the drains,

drenching its enormous wings in filth

as if in its own lovely lake, crying

Where is the thunder, when will it rain??

Elsewhere in Les fleurs du mal, Baudelaire foreshadows Freuds criteria for civilization through beauty, order, and cleanliness.

All is order there, and elegance,

pleasure, peace, and opulence.

Freud concluded Civilization and Its Discontents with a note of optimism, even as fascism took hold in Europe and the future held little hope for Jews, What the world needs is a little more Eros.

Datta, to give, is one of three ways Eliot offers out of a dry, avaricious, and sexless landscape in the concluding section of The Wasteland. Beauty is generosity and reveals itself freely for it must be seen in order to exist. But we vacillate between self and giving, both as individuals and as a society.

Beauty joins grown-ups, like children, in play.

La beaut, said Louise Bourgeois, est la raison dtre.

* * *

A few years ago, I was reading John Ruskin and Walter Pater in my semiotics class. Both taught aesthetics at Oxford in the 1870s. They disagreed on many points, particularly on the use of beauty and its relationship to morality, though neither had any problem employing the word. I complained that the word was seldom used today.

Then Roberto Portillo, a graduate student from Mexico City, waved a little white book by Dave Hickey called The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty. Walking home that evening, book in hand, I saw two lovers in a park near a church on Seventeenth Street: one pressed against the other, the other pressed against a tree, the tree traversed a purple sky.

In an earlier book, The Sense of Beauty (1896), Santayana wrote that if beauty is linked so strongly to the sexual drive, we do not need philosophy to defend it. If one wanted to produce a being with a great susceptibility to beauty, one could not invent an instrument better designed for that object than sex. If people didnt have to unite for the birth and rearing of each generation, they might retain their savage independence. But sex endows the individual with a silent and powerful instinct, which carries each of us continually toward another.

I recommended Hickeys little book to my friend David Shapiro, with whom I share a similar aesthetic. Soon after, perusing an antiquarian bookstore on the fringe of Boston, I found an old anthology called Philosophies of Beauty: From Socrates to Robert Bridges, compiled by E. F. Carritt and published by Oxford University Press in 1931. It included writings by Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Hume, Baumgarten, Kant, Wordsworth, Ruskin, Pater, Nietzsche, Shelley, Santayana, Bergson, Croce, and several others.

With inspiration from Philosophies of Beauty, I felt it might be time for a new anthology on beauty. But if beauty had indeed been dropped from contemporary discourse, would there be enough to fill a book? I asked David to help in the search and we were surprised at how much we found. Soon after, Peter Schjeldahls piece derived from his Notes on Beauty, published herein, appeared as the cover story for the New York Times Magazine. Disparaged for so long in intellectual circles, if not in the popular culture, seething beauty had suddenly resurfaced.

In organizing the book, David and I categorized the writings into three sections: Theory, Ownership, and Practice. The Theory section includes philosophies of beauty from some of todays most important art critics, poets, and philosophers. The oldest essay in this section, dated 1966, is by Meyer Schapiro on the concepts of perfection and unity of form and content. Arthur C. Dantos piece, on the relationship of beauty and morality, redefines for our time a question so close to eminent aestheticians of the nineteenth and early twentieth century like John Ruskin and Henri Bergson. Hubert Damisch contrasts Freud and Kant in the context of his book, The Judgment of Paris. The most recent works are by Robert C. Morgan, Marjorie Welish, and Carter Ratcliff, written specifically for this anthology.

The section we call Ownership encompasses an eloquent debate between Thomas McEvilley, then an editor of Artforum, William Rubin, director emeritus of the Museum of Modern Art, and Kirk Varnedoe, chief curator for painting and sculpture at the museum. The subject of the debate is the exhibition Primitivism in Twentieth-Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern at the Museum of Modern Art, curated by Rubin and Varnedoe in 1984. In this exhibition, contemporary Western works of art were shown side by side with so-called primitive works.

One might ask why this material belongs in a book of essays on beauty. Its overt subject matter is not beauty. But in addressing the affinity artists of the Western world might have for the primitive, the debate cuts to the core of the question of consensus, the relativity of meaning, and the universality of beauty. With McEvilleys initial response to the show, Doctor Lawyer Indian Chief, and the replies that followed in

Next page