NARRATIVES

OF THE

WRECK

OF THE

WHALESHIP

ESSEX

Owen Chase

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 1989 and reissued in 2015, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1935 by The Golden Cockerel Press, London, in an edition limited to 275 copies. The Table of Contents was prepared specially for the Dover edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Chase, Owen

[Narratives of the wreck of the whale-ship Essex of Nantucket which was destroyed by a whale in the Pacific Ocean in the year 1819]

Narratives of the wreck of the whale-ship Essex / Owen Chase, et al.

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: Narratives of the wreck of the whale-ship Essex of Nantucket which was destroyed by a whale in the Pacific Ocean in the year 1819. London: Golden Cockerel Press, 1935.

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-80879-6

1. Essex (Whale-ship) I. Title

G530.E72 1989

CIP

Manufactured in the United States by RR Donnelley

261212052015

www.doverpublications.com

For my friend

A. CROOKS RIPLEY

NARRATIVES

OF THE WRECK OF THE

WHALE-SHIP ESSEX

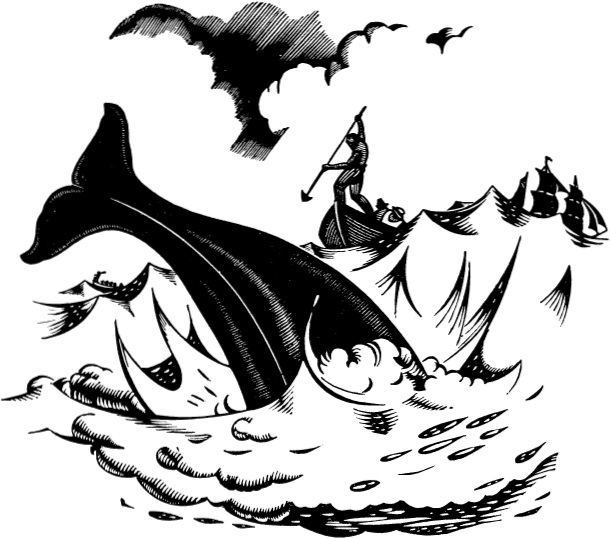

OF NANTUCKET WHICH WAS DESTROYED BY A WHALE IN THE PACIFIC OCEAN IN THE YEAR 1819 TOLD BY OWEN CHASE FIRST MATE THOMAS CHAPPEL SECOND MATE AND GEORGE POLLARD CAPTAIN OF THE SAID VESSEL TOGETHER WITH AN INTRODUCTION & TWELVE ENGRAVINGS ON

WOOD BY ROBERT GIBBINGS

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY THE GOLDEN COCKEREL PRESS LONDON 1935

Title page of the original edition.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

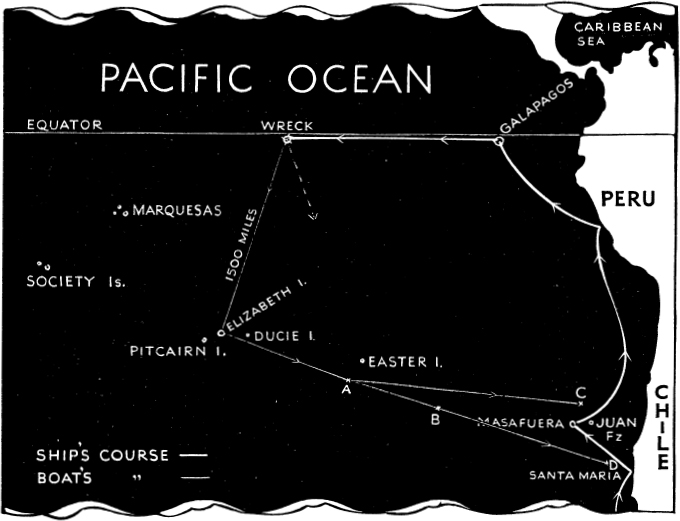

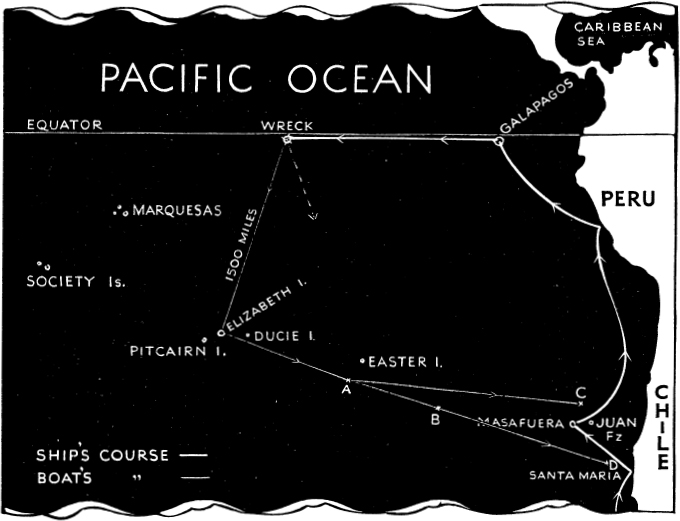

A: Where Owen Chases boat separated from the other two. B: Where the third boat was lost. C: Where Owen Chases boat was picked up. D: Where the Captains boat was picked up.

INTRODUCTION

H ERMAN MELVILLE WAS BORN IN NEW YORK City on August 1st, 1819, and on August 12th of the same year the whale-ship Essex sailed from Nantucket on her last ill-fated voyage. As a result of these two happenings there was published in 1851 a book, by name Moby Dick or the Whale.

In the following narratives we have an account of the loss of the Essex described in detail by the first mate and corroborated in all essentials by the Captain and the second mate. There can be no doubt that their tragic story supplied not only the original idea for Melvilles masterpiece, but in addition was drawn upon, in places almost word for word, for much of the local colour in that tremendous final chapter of his classic.

On this both Raymond Weaver in Herman Melville, Mariner & Mystic, 1921, and Meade Minnigerode in Some Personal Letters of Herman Melville, 1922, are agreed, although they do not give reasons for their statements.

But a comparison of Melvilles romance with the grim facts here printed can leave no doubt in the readers mind.

Not alone is the intelligent malignity of the White Leviathan similiar to the malevolent premeditation of the particular whale described by Chase but the details of the attack are also alike. In each story the ship is struck on the starboard bow and the whale passes under the ship, grazing the length of the keel as he goes along. In each case he attacks twice, in each case the orders Up helm to the steersman are identical. After the attack Chase describes the crew as being like sick women, while Melville writes Let not Starbuck die in a womans fainting fit. The location of the tragedy is the same in both books. The Essex was sunk just south of the Equator in longitude 119 W.; Melville writes that all other whaling waters swept, they were sailing south eastward for the equatorial fishing ground. This lies between longitude 90 and 120 W.

If further proof of indebtedness were needed we know that in Melvilles own copy of The Loss of the Essex there are eighteen pages of notes in his writing, and in Moby Dick, Chapter xlv, he writes:

The Sperm Whale is in some cases sufficiently powerful, knowing, & judiciously malicious, as with direct aforethought to stave in, utterly destroy, & sink a large ship; & what is more, the Sperm Whale has done it.

First: In the year 1820 the ship Essex, Captain Pollard, of Nantucket, was cruising in the Pacific Ocean. One day she saw spouts, lowered her boats, and gave chase to a shoal of Sperm Whales. Ere long, several of the whales were wounded; when, suddenly, a very large whale escaping from the boats, issued from the shoal, and bore directly down upon the ship. Dashing his forehead against her hull, he so stove her in, that in less than ten minutes she settled down and fell over. Not a surviving plank of her has been seen since....

At this day Captain Pollard is a resident of Nantucket. I have seen Owen Chace, who was chief mate of the Essex at the time of the tragedy; I have read his plain and faithful narrative; I have conversed with his son; and all this within a few miles of the scene of the catastrophe.

Apart from literary associations, however, this book has many other interests. It is not only the first authentic account of a ship being rammed and sunk by a whale; it is also an account of truly unparalleled sufferings in an open boat, for though only a few years previously Captain Bligh had made his famous voyage from near Tofua to Timor, a distance of nearly four thousand miles in forty-eight days, the crew of the Essex were at sea for nearly double that time, and however desperate the circumstances in which the survivors of the Bounty found themselves, they were never reduced to the extremity of eating each other, the only means by which any of the Essex survived.

On this point it is interesting to note that in his manuscript journal Bligh says:

This perhaps, does not permit me to be a proper judge on a story of miserable people like us being at last driven to the necessity of destroying one another for foodbut if I may be allowed, I deny the fact in its greatest extent. I say, I do not believe that, among us, such a thing could happen, but death through famine would be received in the same way as any mortal disease.

But though this is the view of a man who had been unpleasantly close to the practical consideration of such a subject, there have been many precedents to the contrary. In the seventeenth century there were seven English sailors blown out to sea from St. Kitts. After seventeen days of starvation they cast lots and killed and ate one of their number. In 1765, the crew of the American sloop Peggy were driven to a like necessity, and in 1816 there was the case of the French frigate Medusa wrecked off the coast of Africa. There are people alive to-day who remember the survivors of The Mignonette being brought ashore at Falmouth. They can show you photographs of the blood-stained boat in which the unfortunate cabin-boy met his death, and they will tell you of the universal sympathy for the sufferers and of the speedy pardon granted to them after their trial.