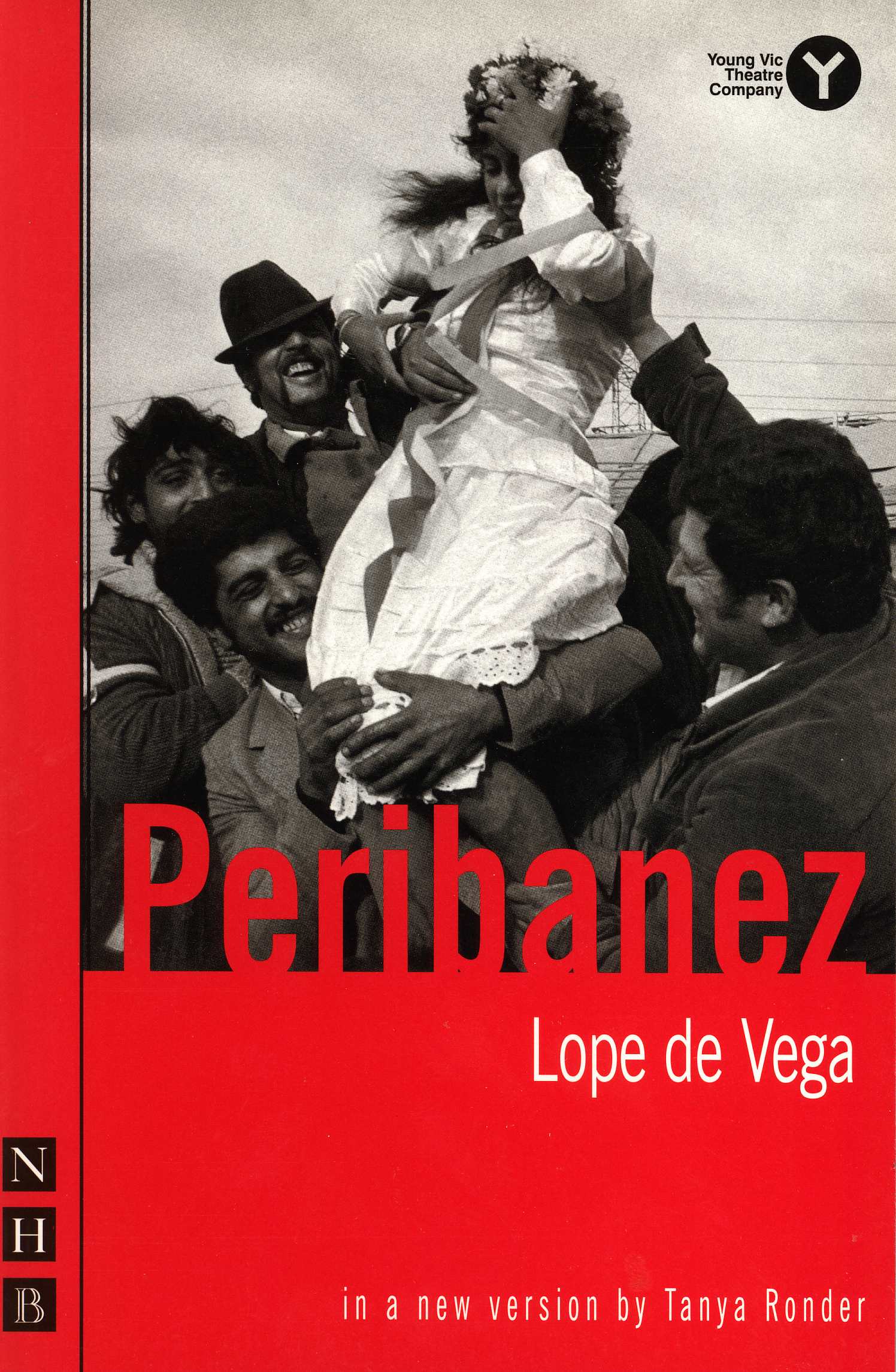

Lope de Vega

PERIBANEZ

in an English version by

Tanya Ronder

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Peribanez was first performed at the Young Vic Theatre, London, on 1 May 2003. The cast was as follows:

PERIBANEZ | Michael Nardone |

CASILDA | Jackie Morrison |

COMMANDER | David Harewood |

INES | Mali Harries |

LEONARDO | Mark Lockyer |

LUJAN | Paul Hamilton |

COSTANZA/QUEEN | Rhiannon Meades |

ANTON/CONSTABLE | Jason Baughan |

BENITO/ARCEO | Robert Willox |

PRIEST/PAINTER/ | Michael OConnor |

HELIPE/LISARDO |

KING/MENDO/VALERIO | Gregory Fox-Murphy |

LLORENTE/FLOREZ | Vincent Patrick |

GIL/MASTER MUSICIAN | John A Sampson |

Director | Rufus Norris |

Designer | Ian MacNeil |

Costumes | Tania Spooner |

Lighting Designer | Rick Fisher |

Sound | Paul Arditti |

Music | Orlando Gough |

Choreography | Scarlett Mackmin |

Musical Direction | Jonathan Gill |

Casting | Wendy Spon |

Fight Direction | Terry King |

Assistant Director | Nizar Zuabi |

Lope de Vega and Peribanez y el Comendador de Ocana

Lope de Vega (15621635) was reading Spanish and Latin and composing verses before he was five. Meanwhile Shakespeare, age three and a half, was cutting his teeth in the English countryside.

Lopes life was full so full its hard to imagine how he fitted it all in. As an adult he was a poet, a sailor on the Spanish Armarda (using poems to a faithless lover to clean his gun), an Inquisitor, had long-lasting affairs with two actresses, married twice and became a father at least six times. He was secretary to two Dukes, killed a man, served a prison sentence, lived in the country and in the town, was an avid gardener and was exiled from Madrid for fouling his ex-lovers name. He became a priest and then lived bigamously with two women in two homes, was widowed, brought up a household of four children from different mothers on his own and wrote plays. As many, its believed, as eight hundred. Only half survive but the ones we have are as varied and full of life as his years on earth.

Lope wrote at a time of change for Spain, when towns were growing into cities. As a result of high taxes and political unrest, the population could no longer rely on the earth for their livelihood. Peasant life on the land was dwindling. Lope wasnt the first playwright to idealise this rural life which belonged to his grandparents generation but he was one of the few to have sampled it first-hand. His peasant world, from which so many of his plays derive, is beautifully detailed. Its an earthy world peopled with animals and characterised by a lack of guile. He places the peasant at the centre of this work politically and emotionally too. Their inner lives and spoken word are more full of poetry, passion, intelligence and self-knowledge than his (often ridiculed) high-born Nobles, Commanders and Royals.

The landless, rural poor were his main interest and, largely, his audience. At the time of writing Peribanez y el Comendador de Ocana, somewhere between 1605 and 1614, there was no way a peasant farmer such as Peribanez could have had access to the King. He didnt possibly couldnt flout all that his society held dear and break such rules, so he has the Commander knight Peribanez during the course of the action and bypasses this difficulty, allowing Peribanez and the king to meet face to face and for the King to save our heros life.

First and foremost Lope de Vega was a peoples playwright. He wrote to entertain. The darker strands in his work nearly always gave way to a happy outcome, even after a costly, bloody journey. He was master of the tragi-comedy. And he vigorously upheld the belief that this was a playwrights job to entertain the masses... Give pleasure to the people and let art be hanged.

In his ironic treatise about the new art of writing plays ( El Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo , published 1609), he divided his audience into those who favoured either this new art championed and created by himself, or the stiffer, literary plays of the older generation. The speed at which he wrote (he complained he spent his life sharpening quills) produced a huge range of plays without concern for consistency of subject or form. For inspiration he drew on chronicles and legends, history and myths, oriental and Italian stories, sacred and chivalrous tomes and popular songs. He did, however, develop highly sophisticated verse forms where the verbal structure helped his audience grasp what was happening. They grew to expect the witty gracioso from the metre in the first line of his speech.

Lope filled Madrids two theatres, the Corral de la Cruz and Corral del Principe, year after year with rowdy and insatiable audiences. They were daytime shows, presented on a plain apron stage with audience (male) in tiers of seats on three sides, no scenery only a curtain along the back through which actors could enter. Above the stage, held up on pillars, was a gallery for musicians where certain scenes took place. There were groundlings (again, men only) who stood at the front and women crowded together in an enclosure at the back. The rich, male and female, watched from boxes which were the windows of houses surrounding the open courtyard.

Plays rarely ran for more than a week. Reviews were spontaneous in the shape of orange peel and soft fruit (Get off!) or rattles and whistles (More please). Lope introduced onto these stages integral music, horses, dancing and other fusions of life. The sixty years during which his plays were performed (he started at twelve and wrote tirelessly, an average of twenty pages a day; his contemporary biographer, Montalvan, asserting that Lope could write a play after mass while his breakfast was warming) forms, along with the plays of Cervantes and Calderon, the Spanish Golden Age.

Although bent on entertainment, the humanist in Lope couldnt help but spill over every page of his work. He knew and loved people; he also knew pain, grief, torture, suffering. His worlds are full of disappointment, temptation and loss in the midst of extreme joy and irrepressible humour. A bonus for us is that his women are as rounded as his men. They are strong, full-blooded, hot-tempered and canny. They may be honest and pure-hearted but they are fallible too. Lopes complex life of intimacy with women is thrown straight back onto the stage, breeding vivid and believable creatures, often embodying a force both natural and vital. Likewise his notion of honour. He doesnt challenge the beliefs of the day but for Lope h onour is more ample and human than the received notion, the prerogative of Noblemen. He invests all his characters with self-respect. The central plot of Peribanez unfurls as a result of a peasants sense of his offended honour.

![Euripides - Classic Greek Drama: 10 Plays by Euripides in a Single File [NOOK Book]](/uploads/posts/book/43473/thumbs/euripides-classic-greek-drama-10-plays-by.jpg)