Zoot Suit Riots

Roger Bruns

Copyright 2014 by ABC-CLIO, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bruns, Roger A., 1941

Zoot suit riots / Roger Bruns.

pages cm. (Landmarks of the American mosaic)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-313-39878-0 (hardcopy : acid-free paper) ISBN 978-0-313-39879-7 (ebook) 1. Zoot Suit Riots, Los Angeles, Calif., 1943. 2. Mexican AmericansCaliforniaLos AngelesSocial conditions20th century. 3. ViolenceCaliforniaLos AngelesHistory20th century. 4. Los Angeles (Calif.)Race relations. 5. Los Angeles (Calif.)Social conditions20th century. I. Title.

F869.L89M4223 2014

306.0979494053dc23 2013033288

ISBN: 978-0-313-39878-0

EISBN: 978-0-313-39879-7

18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook.

Visit www.abc-clio.com for details.

Greenwood

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Recent Titles in Landmarks of the American Mosaic

Abolition Movement

Thomas A. Upchurch

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

John Soennichsen

Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers Movement

Roger Bruns

Tuskegee Airmen

Barry M. Stentiford

Jim Crow Laws

Leslie V. Tischauser

Bureau of Indian Affairs

Donald L. Fixico

Native American Boarding Schools

Mary A. Stout

Negro Leagues Baseball

Roger Bruns

Sequoyah and the Invention of the Cherokee Alphabet

April R. Summitt

Plessy v. Ferguson

Thomas J. Davis

Civil Rights Movement

Jamie J. Wilson

Trail of Tears

Julia Coates

Contents

Series Foreword

The Landmarks of the American Mosaic series comprises individual volumes devoted to exploring an event or development central to this countrys multicultural heritage. The topics illuminate the struggles and triumphs of American Indians, African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans, from European contact through the turbulent last half of the 20th century. The series covers landmark court cases, laws, government programs, civil rights infringements, riots, battles, movements, and more. Written by historians especially for high school students, undergraduates, and general readers, these content-rich references satisfy thorough research needs and provide a deeper understanding of material that students might only be exposed to in a short section of a textbook or a superficial explanation online.

Each book on a particular topic is a one-stop reference source. The series format includes

This landmark series promotes respect for cultural diversity and supports the social studies curriculum by helping students understand multicultural American history.

Introduction

In the Spring of 1943, people in Los Angeles had many wartime concerns. Sailors, soldiers, and marines were in the city in large numbers returning from or preparing to head for battle in the Pacific. The administration of Franklin Roosevelt had already issued orders to remove Japanese Americans from their homes and place them in relocation camps. Fears mounted about Japanese submarines off the coast of California. On February 24, a rumored enemy attack on Los Angeles by the Japanese air force and subsequent anti-aircraft fire by the U.S. military plunged the city into near hysteria. Military officials soon reassured the jittery public that the incident was not a Japanese attack but a false alarm triggered by, among other things, meteorological balloons. And now, in early June, citizens of Los Angeles could read about another war that had broken out, one in their own city, on their own streets. In describing the sudden violence in their midst, local newspapers and tabloids, in heated language, talked about battles and blitzes and perhaps the need for martial law. They talked about anti-Americans in their city, about escalating attacks. But what was this new or other war gripping the city? It had to do with Zoot suits.

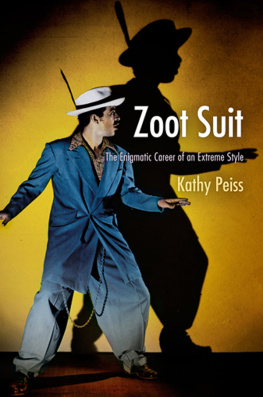

By the 1940s, Mexican-American youths in large numbers were now wearing their own type of uniformthe Zoot suitand they were carrying on their own kind of rebellion, one rooted in a cultural clash nourished through generations. Although it had earlier been something of a black youth fashion identified with the jazz culture, the Zoot suit had been adopted by a generation of Mexican-American teenagers. Along with an oversize coat, with its wide, padded shoulders, most of the boys sported the signature ducktail hair style, long, especially on the sides, and swept back in waves. They also wore a broad-brimmed hat and carried a long watch chain dangling down the side of their pants. Most of them also embraced jazz and other hip music and adopted signature language expressions, derived from Cal, an argot traced to Spanish gypsies.

Some referred to themselves as pachucos and many hung out in groups defined by the neighborhoods in which they lived. Over the years, scholars have traced the roots of the pachuco phenomenon to various sourcesto Spanish gypsies, to lower-class settlers of the Borderlands during the late 18th and 19th centuries, and even to the common soldiers who made up the army of Pancho Villa during the Mexican Revolution of 1910. Other scholars have simply pointed to the pressures of urbanization, ethnic prejudice, and the wracking poverty of the time as the logical, bitter reasons for development of the pachuco culture. To these young people, the Zoot look was both a statement of defiance and an assertion of identity. To most of the general public, however, the Zoot suit represented the decline of the city.

Tensions between the pachuco youngsters and Los Angeles authorities had escalated since the summer of 1942 when the death of a man named Jos Daz sparked a roundup of Zoot suiters as possible suspects. A young Mexican national, Daz was found dead near a reservoir nicknamed Sleepy Lagoon. Los Angeles police herded over 600 Latinos through police stations on the nights of August 10 and 11. Over 20 members of the 38th Street Gang, as described by a local tabloid, were charged with the murder of Daz.

For several weeks before the trial and during it, the racial and cultural divide between the two sidesthe Anglo authorities and the Mexican-American defendantsbecame increasingly clear. A member of the sheriffs department issued a supposedly scientific report to the grand jury considering the case that Mexican Americans were something akin to wild cats, with a predisposition to violence.

During the so-called Sleepy Lagoon Trial, the Mexican-American codefendants were tried en masse. They were not allowed to change their clothestheir Zoot suitsor to cut their hair. The judge reasoned that the jury must be allowed to see the pachucos in their authentic attirethe long, dark, menacing coats and oversize pants. Throughout the proceedings, witnesses talked about the blood lust of Zoot suiters and the ruthlessness that defined their cultural identity.