Table of Contents

To Nathan, Jonathan, David, Daniel, Anna, Elizabeth, and Mary.

To God Alone Be the Glory.

ACCLAIM FOR STEVEN E. WOODWORTHS Nothing but Victory

Comprehensive.... Nothing but Victory presents both the grand strategies and the small incidents that make up the totality and brutality of war.

Nashville Scene

Easily the best book in recent decades about the Civil War beyond the Appalachians. Woodworth skillfully interweaves the letters of semiliterate privates with the reports of officers explaining how they wonor why they lostat places like Shiloh, Vicksburg, Chickamauga, Kennesaw Mountain, and Atlanta.

Ernest B. Furgurson,

author of Freedom Rising: Washington in the Civil War

An excellent account of this remarkable unit and its incredible feats.

Tucson Citizen

Detailing the remarkable feats of the Army of the Tennessee gritty pugnacity, the hard hand of war, a refusal to give up or give inSteven Woodworths Nothing but Victory is an invaluable addition to the literature of the Civil War. Military history buffs will relish it as much as I did.

Jay Winik,

author of April 1865: The Month That Saved America

[Woodworth] balances the strategic, big picture with pertinent small-unit action in this highly readable, long-awaited chronicle of the Unions great army of the West.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

INTRODUCTION

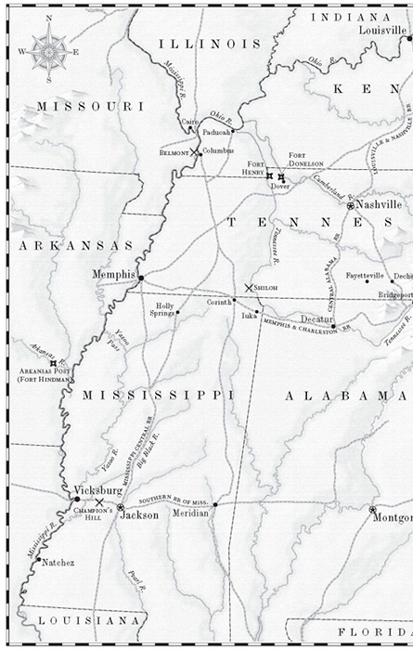

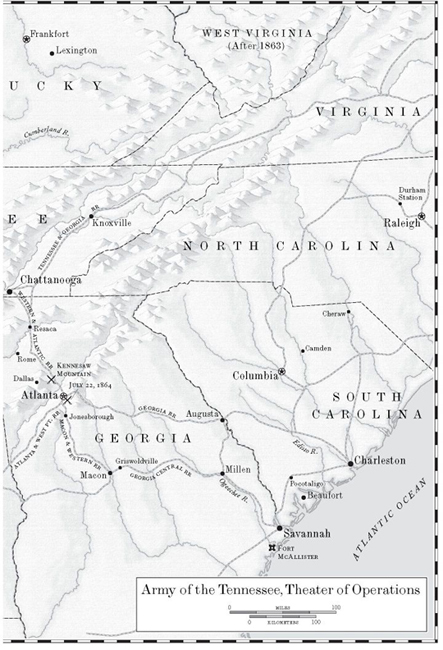

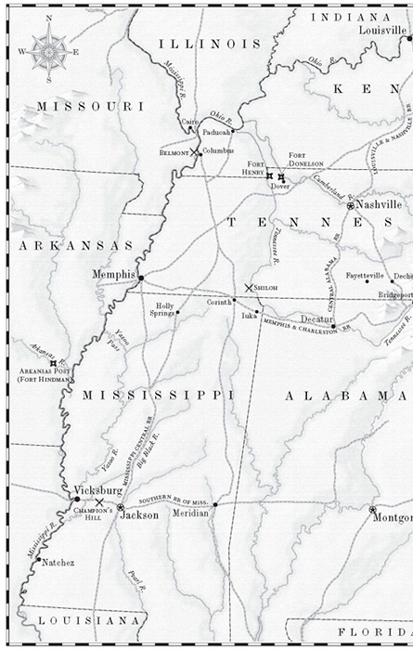

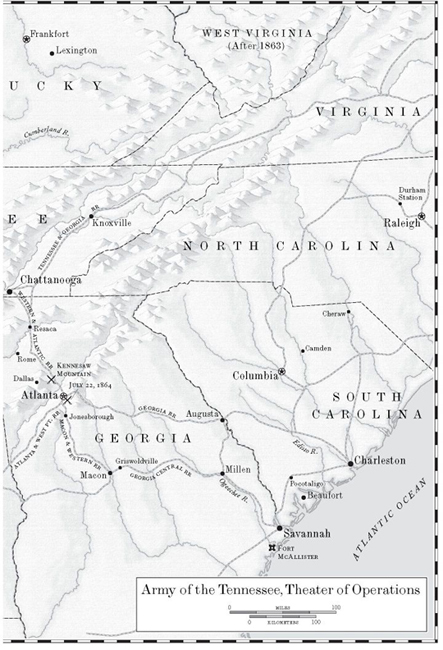

The Army of the Tennessee was the Union field army that fought in the Mississippi Valley during the first three years of the war and then moved east for campaigns in Georgia and the Carolinas during the wars final year. It was present at most of the great battles that became turning points of the warFort Donelson, Vicksburg, and Atlanta. Its desperate fight at Shiloh was the nations first revelation of how bloody the war would be. It made up half of Shermans army during the March to the Sea and the Carolinas Campaign, operations that more than any others revealed to the nation that the war was ending and the Union had won. Though smaller than the highprofile Army of the Potomac, which fought, as it were, in the shadow of the Capitol dome, the Army of the Tennessee won the decisive battles in the decisive theater of the war. With the Army of the Potomac all but deadlocked with its adversary in Virginia and the Army of the Cumberland advancing slowly through Kentucky and Tennessee, it was the Army of the Tennessee that struck the winning blows and penetrated deeply into the heartland of the South.

Just as George B. McClellan shaped the Army of the Potomac in his own image, so Ulysses S. Grant built the Army of the Tennessee in his. It partook both of his matter-of-fact steadiness and his hard-driving aggressiveness. By the midpoint of the war, it had completely imbibed his quiet, can-do attitude, and this spirit continued to characterize its operations even after Grant had moved on to higher command. As the Army of the Tennessee marched away from its familiar Mississippi Valley in the fall of 1863, slinging its knapsacks for new fields, Capt. Jacob Ritner of the 25th Iowa wrote to his wife back in Mount Pleasant, Our army never was in better spirits or more enthusiastic in the cause than at present. We all expect a hot fight before long, but we expect nothing but victory.1 That was typical of the Army of the Tennessee. Nothing but victory was what that army expected and was usually what it experienced. Nor is it any coincidence that Grants qualities tended to be those of that up-and-coming region of the country, one day to be called the Midwest, from which the army was almost exclusively recruited. The men were quick to adopt Grants approach to war, because it was the way their own fathers had approached the challenges of carving farms out of the wilderness.

Perhaps a word is in order about nomenclature. Although the army received its official title as the Army of the Tennessee only in October 1862, I decided to cover it from its genesis in the camps around Cairo, Illinois, in the summer of 1861 and, even before that, the recruitment of the soldiers. For simplicitys sake, I will refer to it throughout as the Army of the Tennessee. Another matter of nomenclature has to do with the term Midwest. It was not in use in the mid-nineteenth century, and therefore some might contend that I should not use it. However, although I am telling this story about people who lived in the nineteenth century, I am telling it to people who live in the twenty-first. The terms Midwest and Midwestern communicate well to my intended audience, and therefore I will occasionally use them. The term that mid-nineteenth-century Americans would have used was Northwest. The Old Northwest referred to the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, but the region had come to include Iowa and Minnesota as well. For the sake of variety and a touch of authenticity, I will sometimes use the term Northwest as being synonymous with Midwest.

In telling the story of the Army of the Tennessee, I have made a number of decisions about what I would cover and what I would regretfully pass over. One fundamental decision was to maintain a focus on that part of the Army of the Tennessee that operated directly under Army of the Tennessee headquarters. Thus, I have not covered the Thirteenth Corps in the trials and tribulations it experienced after its unfortunate transfer to the Department of the Gulf or the triumphs of A. J. Smiths wing of the Sixteenth Corps functioning as Grants de facto strategic reserve during the last year of the war. I have passed lightly over the activities of the Seventeenth Corps in Mississippi during the autumn of 1863 and of Peter Osterhauss division when it functioned under the command of Joseph Hooker in that same period. In each of these cases, my decision was based on giving maximum coverage to units functioning with the main Army of the Tennessee.

That said, this is by no means a headquarters history. My goal has been to present a narrative of the army with attention to all levels, from that of commanding general all the way down to the newest recruit. It was the common soldiers that interested me most, and I have endeavored to convey the flavor of their thoughts, attitudes, and actions throughout this account. After years of poring through their diaries and letters, I feel as though Ive come to know them on an almost personal basis, and my respect for them continues to grow.

PART ONE

Grants Army

CHAPTER ONE

Raising an Army

RED SNOW FELL near Iowa City, reported the Des Moines Sunday Register on March 5, 1861. Editor George Mills hastened to explain that the color was caused by fine flakes of reddish clay mixed with the precipitation. Wind had swept dust into the atmosphere far to the west, providing the residents of eastern Iowa with a bit of unusual late-winter color. It was a simple scientific explanation, easily understood by modern Americans in this enlightened second half of the nineteenth century. Yet as editor Mills observed, many Iowans could hardly help wondering whether the eerie reddish cast of their normally snow-whitened plains was not some vague but appalling portent of terrible things to come. It may well have occurred to some Hawkeyes that the next winters snows might be reddened by the bloodshed of civil strife. Americans elsewhere would have asked themselves the same question.1

Next page